Preventable Tragedies

Unintentional Shootings by Children

Last Updated: 4.26.2023

Executive Summary

“It has affected our whole lives,” Haley Rinehart, whose 4-year-old son found an unsecured, loaded gun at a relative’s home and shot and wounded himself in the head in 2002. “Even almost 20 years later, we’re still dealing with the aftermath of all of this. I don’t know if there will ever be any full closure. It’s like a wound that never heals.”

—Haley Rinehart in conversation with Everytown for Gun Safety1Haley Rinehart in conversation with Kaelyn Forde, Everytown for Gun Safety, July 19, 2021.

Every year, hundreds of children in the United States gain access to unsecured, loaded guns in closets and nightstand drawers, in backpacks and purses, or just left out in the open. With tragic regularity, children pick up these unsecured guns and unintentionally shoot themselves or someone else.

While unintentional shootings by children are a heartbreaking part of America’s gun violence epidemic, there is no centralized database that tracks how many children gain access to loaded guns and harm themselves or others. Everytown started such a database in 2015 by carefully tracking media reports to explore this crisis in depth.

Key Findings

An analysis of the over 2,800 incidents that took place between 2015 and 2022 in which a child under the age of 18 unintentionally shot themself or others, included in the #NotAnAccident Index, reveals the following:

- Nearly one child gains access to a loaded firearm and unintentionally shoots themself or someone else every day in America—an average of 350 children a year.

- The victims of shootings by children are most often also children. Over nine in 10 of those wounded or killed in unintentional shootings by children were also under 18 years old.1Of the 2,898 victims of unintentional child shootings (people shot and wounded or killed) in the eight-year period, 2,655 were under age 18. Age group was unknown for 1 percent of the victims. Of the total 2,802 incidents, 49 percent involved the child shooting themself, 47 percent involved the child shooting other people, 2 percent involved the child shooting themself and other people, and in 3 percent of the incidents, it was unknown whether the child shot themself or another child shot them. #NotAnAccident Index.

- More than seven in 10 unintentional child shootings occur in or around homes.

- Unintentional shootings occur most frequently at times when children are likely to be home: over the weekend and in the summer.

- The two age groups most likely to unintentionally shoot themselves or others are high schoolers between the ages of 14 and 17, followed by preschoolers age five and younger.

- Nearly one in every three unintentional shooters were preschoolers. Since 2015, the proportion of shootings by children five and under has increased while those by high schoolers has declined.

- When children unintentionally shoot another person, the victim is most often a sibling or a friend.

- The 10 states with the highest rates of unintentional child shootings had rates that were, on average, over 10 times higher than those of the 10 states with the lowest rates.

- States with secure storage or child-access prevention laws had the lowest rates of unintentional child shootings. Rates of unintentional shootings by children were 34 percent lower in states with laws that hold gun owners accountable when children do gain access to an unsecured gun, compared to states without such laws.

While these statistics are deeply distressing, this report also outlines the effective steps we can take to keep guns out of children’s hands and save the lives of children, teens, and adults. This includes secure gun storage practices, public awareness campaigns, and laws proven to reduce unintentional injuries and deaths. To learn more about secure firearm storage, visit BeSmartForKids.org.

Introduction

Firearms are the leading cause of death for children under age 18 in the United States.2Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, WONDER Online Database, Underlying Cause of Death, Injury Mechanism & All Other Leading Causes, 2021, https://wonder.cdc.gov/controller/saved/D158/D323F580. Ages 1 to 17. While the vast majority of these gun deaths are homicides and suicides, unintentional shootings—which make up 5 percent of annual gun deaths among children 17 and younger—are a persistent and heartbreaking aspect of this public health crisis.3Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, WONDER Online Database, Underlying Cause of Death, https://wonder.cdc.gov/controller/saved/D158/D329F697. A yearly average was developed using four years of the most recent available data: 2018 to 2021. Ages 0 to 17. They are also preventable when families take steps to reduce children’s access to firearms in their own homes and in homes that children are visiting.

It’s not just the child who’s injured or killed who is affected by these incidents. It’s their siblings and their cousins and their parents and their entire community. Staff at local schools come to us to help work through the trauma in the entire school when one of these incidents occurs. And it affects the medical personnel who treat them as well. I can’t tell you the number of pediatric residents who have come to me after being in the trauma bay when one of these children rolls in. It’s just so tragic for everybody involved.

—Dr. Annie Andrews in conversation with Everytown for Gun Safety4Dr. Annie Andrews, MD, MSCR, associate professor in the Department of Pediatrics at the Medical University of South Carolina in conversation with Kaelyn Forde, Everytown for Gun Safety, July 21, 2021.

Tracking Unintentional Shootings by Children

#NotAnAccident Index

In 2015, Everytown for Gun Safety started tracking unintentional shootings by children, collecting information through media reports about incidents in which a child under 18 unintentionally shot themself or someone else. The data referenced in this report can be found in this data tracker.

While the incidents included in the #NotAnAccident Index are limited to those in which the shooter was 17 or younger, the victims from these unintentional shootings ranged from a 1-month-old baby boy to a 77-year-old man. When children shoot another person, the victims and survivors are too often their own siblings, cousins, friends, parents, or grandparents. These shootings leave multiple families and their extended communities facing grief, regret, and years of physical, emotional, and sometimes legal and financial consequences. The analysis of eight years’ worth of these incidents can help steer us toward the most effective solutions.

Uncovering Solutions Through the Data

Shooter and Victim Demographics

From January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2022, there were at least 2,802 unintentional shootings by children ages 17 and younger resulting in 1,083 people killed and 1,815 people wounded. And nearly all of those victims and survivors (92 percent) were also children under 18.

Of the eight years for which Everytown has tracked unintentional shootings, 2021 saw the highest number of incidents (395), deaths (166), injuries (248), and total victims (414). After a two-year decline in 2018 and 2019, the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic saw a surge in these shootings along with a simultaneous surge in gun sales.5Daniel Nass and Champe Barton, “How Many Guns Did Americans Buy Last Month?” The Trace, March 6, 2023, https://www.thetrace.org/2020/08/gun-sales-estimates/. The number of unintentional deaths resulting from shootings by children in 2020 and 2021 was a staggering 40 percent higher than the previous two years.6From 2018 to 2019, there were 616 unintentional shootings by children resulting in 220 people killed and 421 people wounded. From 2020 to 2021, there were 764 unintentional shootings by children resulting in 308 people killed and 490 people wounded. There was a 24 percent increase in unintentional shooting incidents, a 40 percent increase in unintentional deaths, and a 16 percent increase in nonfatal injuries in 2020–2021, compared to 2018–2019.

Unintentional shootings by children surged during the COVID pandemic.

Children who unintentionally fired the gun in these incidents from 2015 to 2022 ranged from toddlers and preschoolers to teenagers. In fact, while 14- to 17-year-olds made up the largest age group impacted by these incidents—and were most likely to be the shooters—children five years and younger were the second-largest age group impacted and were most likely to be the victims. During this period, at least 895 preschoolers and toddlers aged five and under managed to find a gun and unintentionally shoot themselves or someone else with at least 933 children under five were shot and wounded or killed. In other words, nearly one in every three shooters and victims, respectively, were ages five and younger.7Of the 2,802 shooters, 895 (32 percent) of them were ages five or younger, and of the 2,898 victims, 933 (32 percent) were ages five or younger. #NotAnAccident Index.

Two age groups account for the largest share of both shooters and victims: high schoolers and children five and younger.

Toddlers’ and pre-kindergarteners’ access to guns are the primary drivers of the recent increase in these unintentional shootings. From 2015 to 2022, the number of shootings by children five and under increased 33 percent while shootings among 14- to 17-year-olds decreased 28 percent. In 2021 alone, a record 148 children ages five and under unintentionally shot themself or someone else.

Shootings by toddlers and pre-kindergarteners have increased while shootings among high schoolers have decreased.

As with firearm homicides and suicides, the same holds true for unintentional shootings: gun violence in all its forms is largely perpetrated by males. Boys made up the overwhelming majority of those both involved in and impacted by unintentional shootings: 81 percent of shooters were boys and 76 percent of victims were boys and men.8Of the 2,802 shooters, 81 percent were male and 8 percent were female, while gender was unknown for 11 percent. Of the 2,898 people shot and wounded or killed, 76 percent were male, 19 percent were female, and 5 percent were of unknown gender. #NotAnAccident Index.

While the race and ethnicity of both the shooters and victims are key demographic aspects of these incidents, this information is not systematically documented. Using both media tracking and court record reviews, Everytown was unable to obtain the race or ethnicity of 81 percent of all shooters and 72 percent of victims over the eight years studied. This is largely because the shooters and most victims are children, and as such, they benefit from laws and practices related to protecting the privacy of minors. However, incidents that result in death often have more in-depth news coverage than those resulting in nonfatal injuries, allowing for the collection of demographics. A review of incidents resulting in death between 2019 and 2022 in our database revealed that at least 27 percent of the 580 shooters were Black or likely Black based on a parent’s race and at least 11 percent were white or likely white.9Race was unknown for 55 percent of shooters and 8 percent of shooters were another race/ethnicity. During the same period, at least 43 percent of the 581 people killed were Black or likely Black and 17 percent were white or likely white.10Race was unknown for 24 percent of people killed and 15 percent were another race/ethnicity.

Finally, unintentional shooting deaths and injuries are as likely to be self-inflicted as they are to be inflicted by someone else.11Of the 2,802 incidents, 49 percent involved the child shooting only themself, 46 percent involved the child shooting other people, 2 percent involved the child shooting themself and other people, and in 3 percent of cases, it was unknown whether the child shot themself or another child shot them. #NotAnAccident Index. Since stages of brain development and socialization vary widely from infants to adolescents and teenagers, we examined the relationship between the victim and shooter broken down by shooter age group. Whereas at least 75 percent of the victims of children five and younger were the children themselves, 60 percent of the victims of teenagers 14 to 17 were other people, most often friends.12Among the victims of shooters ages 0–5, 75 percent were themself and 25 percent were another person; among those shot by 6–10 year olds, 48 percent were themself and 52 percent were another person; among those shot by 11–13 year olds, 39 percent were themself and 59 percent were another person; and among those shot by 14–17 year olds, 39 percent were themself and 60 percent were another person. Among the remaining victims, it was unknown if the shooter shot themself or someone else. When children unintentionally shoot someone else, the younger age groups are most likely to shoot a family member—often a sibling—but as children age, their friends become increasingly more likely to be their victims. Though adults make up a smaller portion of victims, they are not immune to this danger. Parents accounted for just 5 percent of all victims in incidents where a child unintentionally shot someone else; however, parents are the second most likely victims of shootings by children ages five and younger, making up 23 percent of their victims.13At least 74 parents were unintentionally shot by their child. Among them 53 (72 percent) were shot by a child age five or younger.

When children unintentionally shoot someone else, the victim is most often a sibling or friend.

While suicide with a firearm is a devastating and growing problem among American youth, the self-inflicted injuries and deaths included in this dataset are not the result of suicide or attempts at self-harm. Rather they are often situations where the child accessed and fired a gun they did not realize was loaded.14The determination as to whether a self-inflicted gun injury or gun death was unintentional, a suicide, or suicide attempt is weighed carefully in this dataset. For older children and teenagers, a self-inflicted gun death that does not include a clear determination of intent (for example, by law enforcement) would not be included in this database of unintentional shootings. It might instead be categorized as a suicide. However, in the case of younger children when the intent is not clearly determined, researchers review available information and make a determination as to whether the shooting circumstances indicate intentional self-harm or an unintentional incident. See Methodological Note for further details. The stories of these shootings are harrowing—and avoidable. Four-year-old Eli’s story outlines the innocence of a tragedy in the Rinehart family.

Haley’s Story

“The hardest thing I’ve ever had to do in my life.”

Location, Month, and Day of the Week

Analysis of these incidents points clearly to the far greater likelihood of unintentional shootings occurring when children are home from school and to the importance of secure gun storage in gun-owning homes:

- The average number of shooting incidents by children per day was highest in summer. July’s average of 1.2 unintentional child shootings per day was 46 percent higher than the April and September averages (0.82).

- Unintentional child shootings were more likely to happen on Friday through Sunday, with Saturday being the most common day.

- Over seven in 10 unintentional shootings by children in 2015 through 2022 occurred in or around a home—either that of the shooter, the victim, a friend or relative, or someone else.

Unintentional Shootings by Children by Month

Unintentional Shootings by Children by Day of the Week

Seven in ten unintentional shootings by children occur in a home.

ASHLYN’S STORY

“He was sleeping at his friend’s house for the holiday. He never came home.”

Type of Gun

While media reporting on these incidents does not always include details about the type of gun used, information obtained for 59 percent of unintentional child shootings shows that handguns accounted for the great majority (86 percent) of incidents. Rifles and shotguns accounted for 7 and 6 percent, respectively, and assault-style weapons made up at least 1 percent of the guns accessed in unintentional shootings by children.15Firearm type was unknown for 1,154 incidents. Percentages are based on 1,648 incidents with known firearm types. #NotAnAccident Index.

Looking at the data broken into two age groupings, we found that a somewhat higher proportion of incidents among children in the younger group (up to age 9) involved a handgun than among the older group (ages 10 to 17). Handguns were used in 93 percent of incidents in the younger group and 80 percent in the older group.

Handguns account for the bulk of gun types accessed by children in unintentional shootings.

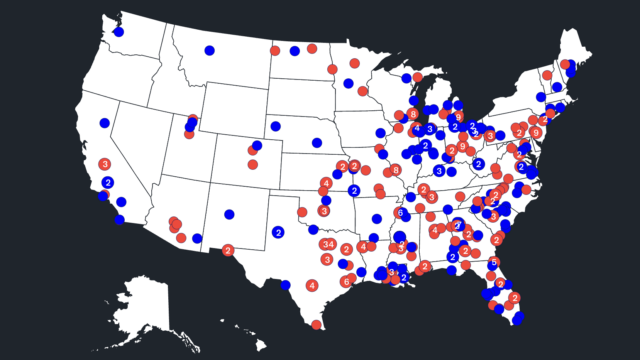

Variation by State

A state-by-state analysis of the 2,802 unintentional shootings since 2015 reveals a tremendous range among states. While there were 248 such incidents in Texas16Texas has the 27th-highest rate of unintentional shootings by children at 4.2 per 1 million children. over the eight-year period of this report, Hawaii and New Hampshire had one incident each, and none were recorded in Rhode Island. Further findings include:

- The 10 states with the highest rates of unintentional shootings per 1 million residents under 18 were Louisiana, Mississippi, Tennessee, Missouri, Alaska, South Carolina, Alabama, Georgia, Ohio, and Indiana.

- The 10 states with the lowest rates—where unintentional shootings by children were rare or never happened—were Rhode Island, Hawaii, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, California, New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Washington, and Wyoming.

- The 10 states with the highest rates of unintentional shootings by children were on average over 10 times higher than the 10 states with the lowest rates (10.5 per 1 million children compared to 1.0 per 1 million children).

Rates of unintentional shootings by children by state vary enormously.

These vast differences in unintentional shootings by state can be attributed in part to gun ownership rates. It stands to reason that the likelihood of a child accessing a gun is linked to gun ownership in that home and community, and our dataset shows this association clearly. The states with the highest household gun ownership rates (where 50 percent or more households in that state are gun-owning households) have nearly quadruple the rate of unintentional shootings by children compared to the states with the lowest gun ownership (where under 30 percent of households own guns).17Household gun ownership data for 2016 comes from RAND Corporation, “Gun Ownership in America,” accessed November 3, 2022, https://www.rand.org/research/gun-policy/gun-ownership.html. The rate of unintentional shootings by children is 8.9 per 1 million children in states with the highest rates of household gun ownership (50 to 65 percent): AK, AL, AR, ID, KY, LA, MO, MS, MT, ND, OK, SD, VT, WV, WY. The rate of unintentional shootings by children is 2.3 per 1 million children in states with the lowest rates of household gun ownership (9 to 29 percent): CA, CT, FL, HI, IL, MA, MD, NJ, NY, RI.

But this is not the end of the story. Policy also matters.

Impact of Gun Storage Policies

Can storage policies related to children’s access to firearms prevent unintentional child shootings? Looking at incidents state-by-state and their corresponding laws, the 10 states where unintentional shootings by children were lowest (with the exception of Wyoming) all have one important thing in common: they have some form of child-access law that provides protection against these shootings, commonly known as secure storage laws. In sharp contrast, the 10 states with the highest rates of unintentional child shootings do not have such a law, or have a secure storage law that only applies in extremely limited circumstances.

States with the Lowest Shooting Rates Have Strong Firearm Storage Laws

| Rank (lowest rate = 51) | State | Number of unintentional shootings by children | Rate per 1 million children | Secure Storage law? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 51 | Rhode Island | 0 | 0 | Yes (if child accesses) |

| 50 | Hawaii | 1 | 0.4 | Yes (if child accesses) |

| 49 | New Hampshire | 1 | 0.5 | Yes (if child accesses) |

| 48 | Massachusetts | 6 | 0.6 | Yes (every time not in owner’s possession) |

| 47 | California | 69 | 1.0 | Yes (if child is likely to access) |

| 46 | New Jersey | 17 | 1.1 | Yes (if child accesses) |

| 45 | New York | 38 | 1.2 | Yes (if child is likely to access) |

| 44 | Connecticut | 10 | 1.7 | Yes (if child accesses) |

| 43 | Washington | 24 | 1.8 | Yes (if child accesses) |

| 42 | Wyoming | 2 | 1.9 | No |

States with the Highest Shooting Rates Have Weak or No Firearm Storage Laws

| Rank (highest rate = 1) | State | Number of unintentional shootings by children | Rate per 1 million children | Secure Storage law? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Louisiana | 136 | 15.5 | No |

| 2 | Mississippi | 75 | 13.3 | Only if intentional or reckless |

| 3 | Tennessee | 134 | 11.1 | Only if intentional or reckless |

| 4 | Missouri | 116 | 10.5 | Only if intentional or reckless |

| 5 | Alaska | 15 | 10.3 | No |

| 6 | South Carolina | 87 | 9.9 | No |

| 7 | Alabama | 81 | 9.2 | No |

| 8 | Georgia | 174 | 8.7 | Only if intentional or reckless |

| 9 | Ohio | 173 | 8.3 | No |

| 10 | Indiana | 103 | 8.2 | Only if intentional or reckless |

At the end of 2022,18For the most up-to-date list of states with secure storage laws, visit https://everytownresearch.org/rankings/law/secure-storage-or-child-access-prevention-required/. 23 states and Washington, DC, had some form of gun storage law holding gun owners accountable when children can or do access an unsecured gun.19During the study period, four states (Maine, New York, Oregon, and Washington) enacted secure storage laws after having no laws, Colorado enacted a secure storage law after previously having an intentional/reckless law, and Nevada strengthened its secure storage law changing its application from when a child does access a gun to when a child is likely to access one. These laws fall along a spectrum from most protective to least:

- The most protective and comprehensive laws require the gun owner to secure their firearms whenever they are not in their immediate possession or control (two states: Massachusetts and Oregon).

- The next most protective and comprehensive laws apply if a child is likely to access an unsecured gun (six states and Washington, DC).

- Less comprehensive are laws that apply if a child does access an unsecured gun (15 states).

- The laws that are least protective apply only when a gun owner intentionally or recklessly provides a firearm to a child. But these laws apply in such limited circumstances that they are not considered “secure storage” laws (10 states).

- The least protective circumstance is having no child-access-related laws at all (17 states).

Secure Storage Laws by State, 2022

Last updated: 12.31.2022

Compared to states with no secure storage laws, rates of unintentional shootings by children were 78 percent lower in states requiring secure storage when the gun is not in the owner’s possession. Switching to this level of protection could save countless lives. Among the other categories, rates of shootings were 39 percent lower in states with laws that apply when a child is likely to access a gun, and 34 percent lower in states with laws that apply when a child does access a gun than in states with no secure storage laws. Finally, states with laws that apply only if the gun owner intentionally or recklessly gives a child access to a gun had similar rates of unintentional shootings by children as those without any laws.20Negative binomial regression results: Law requires secure storage when gun is not in owner’s possession (RR: 0.22, 95% CI: 0.11–0.32, p<.01); Law applies if child is likely to access an unsecurely stored gun (RR: 061, 95% CI: 0.43–0.87, p<.01); Law applies if child does access an unsecurely stored gun (RR: 0.66, 95% CI: 0.51–0.84, p<.01). Law applies if owner intentionally or recklessly gives gun access to a child (RR: 1.08, 95% CI: 0.88–1.34, p=0.46). Models controlled for the percentage of the population with less than a high school education, percentage of the population that is male, unemployment rate, population density, mean household income, homicide death rate, and suicide death rate; and included fixed effects for year and census division. Six states changed their laws during the study period.

78%

Rates of unintentional shootings by children were 78 percent lower in states requiring secure storage when the gun is not in the owner’s possession, compared to states with no secure storage laws.

Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, “Preventable Tragedies: Unintentional Shootings by Children,” 2023, https://everytownresearch.org/report/preventable-tragedies-unintentional-shootings-by-children/.

Last updated: 4.12.2023

39%

Rates of unintentional shootings by children were 39 percent lower in states with laws that apply when a child is likely to access a gun, compared to states with no secure storage laws.

Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, “Preventable Tragedies: Unintentional Shootings by Children,” 2023, https://everytownresearch.org/report/preventable-tragedies-unintentional-shootings-by-children/.

Last updated: 4.12.2023

34%

Rates of unintentional shootings by children were 34 percent lower in states with laws that apply when a child does access a gun, compared to states with no secure storage laws.

Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, “Preventable Tragedies: Unintentional Shootings by Children,” 2023, https://everytownresearch.org/report/preventable-tragedies-unintentional-shootings-by-children/.

Last updated: 4.12.2023

While this research focuses on laws to prevent unintentional firearm injuries and deaths at the hands of children, secure gun storage laws can prevent youth suicides, gun theft, and violent crimes by youths or adults as well.21RAND Corporation, “The Effects of Child-Access Prevention Laws,” January 10, 2023, https://www.rand.org/research/gun-policy/analysis/child-access-prevention.html.

Recommendations

As is clear from the preceding discussion, secure gun storage is the indispensable ingredient needed to avert these incidents—tragedies that happen with painful regularity at times and in places where children are simply being children. Recommendations include secure gun storage practices, public education campaigns, and laws.

Secure Gun Storage Practices

Talking with children about guns is a good precaution, and those conversations should evolve as children grow older. But it does not guarantee their safety. Children are endlessly curious and exploration is one of the hallmarks of childhood. One study found that young children who go through a week-long gun safety training program are just as likely as children with no training to approach or play with a handgun when they find one.22Marjorie S. Hardy, “Teaching Firearm Safety to Children: Failure of a Program,” Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 23, no. 2 (April 2002): 71–76, https://doi.org/10.1097/00004703-200204000-00002. That is why it is always an adult’s responsibility to prevent unauthorized access to guns, not a child’s responsibility to avoid them.

An important part of that responsibility is asking about guns in any home your child visits. We routinely take precautions in other areas of life by asking relatives or the parents of our children’s friends about pets in their homes, allergens, car seats, and more. Asking about whether they own guns and whether they are securely stored should be part of these safety discussions. Some people may find this initially to be an awkward conversation. The Be SMART campaign provides helpful tips on how to conduct this conversation.

The next secure gun storage practice relates to the actual device used for storage. US gun-owning households have an average of eight guns23Christopher Ingraham, “The Average Gun Owner Now Owns 8 Guns—Double What It Used to Be,” Washington Post, October 21, 2015, https://wapo.st/3yiPd95. that are often a variety of types of equipment used for a variety of purposes. These uses can include sport and recreation, gun collecting, and protection. Responsible gun owners know to practice gun safety at all times to prevent firearms access by any unauthorized user.

The approach and kind of devices used to store firearms vary depending on important considerations, such as how many children are in the household or are likely to visit and what age they are, as well as the presence of anyone who may be a danger to themselves or others. Practicing gun safety means storing firearms unloaded, locked, and separate from ammunition and secured to a structure in the house (such as a wall or heavy piece of furniture) in order to prevent theft. One study found that households that kept both firearms and ammunition locked were associated with an 85 percent lower risk of unintentional firearm injuries among children and teens, compared to those that locked neither.24David C. Grossman et al., “Gun Storage Practices and Risk of Youth Suicide and Unintentional Firearm Injuries,” JAMA 293, no. 6 (2005): 707–14, https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.293.6.707.

Assume children and teens can find guns. Store firearms unloaded, locked, and separate from ammunition.

Finding a storage arrangement for guns kept in homes for protection can be more challenging. However, secure gun storage practices do not prevent a gun from being accessed quickly in a self-defense scenario. In fact, there are affordable options for gun storage that provide owners with access to a gun in a matter of seconds, while still keeping those guns out of the hands of children and people who are at risk of harming themselves or others.

There are three key considerations for storing guns so that they can be easily accessed for home defense, but not by minors, thieves, or other unauthorized users:

- Locked boxes are far preferable to other types of gun locks, such as cable and trigger locks, because they fully contain the gun so that children cannot see what is inside and because they offer stronger protection.

- Locked boxes that can be opened only by authorized individuals provide important safety. Some of the fastest locked boxes open using the owner’s fingerprints in only half a second. Boxes that open with RFID “smart” tags using chip technology also allow very quick access. Boxes opened with keys or a combination are less desirable options due to the ease of others finding the key or figuring out the code.

- Owners should choose a storage device that can be secured so that the gun cannot be stolen. Companies manufacture gun storage devices that can be secured in any part of the house.

While the self-defense use for a gun may be a priority, it is also essential to be realistic about the safety and effectiveness of that use. A 2015 study by researchers at Harvard University and the University of Vermont, using data from 2007 to 2011, found that one’s chances of being injured in a self-defense situation with a gun or from other self-protective measures (such as running away or screaming for help) are roughly the same. There is little evidence that using a gun for self-defense reduces the danger of either sustaining an injury or losing possessions during a crime.25David Hemenway and Sara J. Solnick, “The Epidemiology of Self-Defense Gun Use: Evidence from the National Crime Victimization Surveys, 2007–2011,” Preventive Medicine 79 (October 2015): 22–27, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.03.029. Finally, guns kept quickly accessible for home protection are twice as likely to be stolen as to be used to stop a crime.26Center for American Progress analysis of the National Crime Victimization Survey: “While guns were used for self-defense in 85,000 crimes per year from 2010 to 2015, roughly 162,000 guns are stolen each year.” Center for American Progress, “Myth vs. Fact: Debunking the Gun Lobby’s Favorite Talking Points,” October 5, 2017, https://ampr.gs/2Vn948w. In this way, unsecured guns may actually increase the likelihood of crime and violence through an increased risk of theft.

There is little evidence that using a gun for self-defense reduces the danger of either sustaining an injury or losing possessions during a crime.

Homes are not the only places guns should be securely stored, they should be secured when in cars as well. More than 200 unintentional shootings by children occurred in cars, while some shootings at other locations involved guns stolen from cars.27See, for example, Douglas Walker, “Victim’s Mother Calls for ‘Accountability’ in Fatal Shooting,” Muncie Star Press, January 23, 2023, https://bit.ly/3Fvq6pn; Graham Cawthon, “Police: Georgia Teen Charged with Murder After 12-year-old Child Shot in the Head,” WJCL, May 4, 2022, https://bit.ly/42kD96Q; Bill Grimes, “Update: Parents Express Pain of Loss During Sentencing in Fatal Shooting,” Effingham Daily News, April 14, 2016, https://bit.ly/40dcy9P. With research showing that cars are now the largest source of stolen guns, secure storage in cars is an important component in preventing unintentional shootings and other forms of gun violence.

Secure Gun Storage Public Education

The number of unintentional child shootings detailed in this report tells us we must urgently do better to get the word out about the importance of secure firearm storage. Everyone in the community can play a role—from gun sellers and law enforcement, to schools and doctors, to elected officials and community members—in shaping messages and developing options that are appropriate for local contexts. Some important initiatives include:

General Education Campaigns

Awareness campaigns to promote public health have been extremely effective in changing behaviors related to a variety of major issues, including smoking, wearing seat belts, and impaired driving. For secure gun storage and reducing unintentional child shootings, one such campaign is Be SMART, an effort launched by Everytown that emphasizes that it’s an adult’s responsibility to keep kids from accessing guns, and that every adult can play a role in keeping kids and communities safer. There are thousands of Be SMART volunteers across the country helping parents and adults normalize conversations about gun safety through online training, booths at county fairs and farmer’s markets, National Night Out campaigns, and many more events.

Other efforts include Brady’s End Family Fire campaign. In collaboration with the Ad Council, Brady has produced ads, social media graphics, public service announcements, training, and other initiatives to promote responsible gun ownership and secure storage.28https://www.endfamilyfire.org

Firearms and Sporting Goods Stores

As a start, partnerships between gun shops, gun storage device sellers, hospitals, or local governments to educate people on secure storage are yet another way to get the word out. Seattle and King County Public Health have a partnership with a number of online and in-store retailers through which they provide educational posters and brochures, as well as discounts on storage devices. In addition, all gun safes and lock boxes are tax exempt in the state of Washington, as they are in other states as well.29Seattle & King County Public Health, “Lock It Up: Purchase Safe Storage Devices,” accessed July 30, 2021, https://bit.ly/3liovtx.

Schools

Since 2019, school districts across the country have passed resolutions to require that information be sent home with students to educate parents about the importance of securely storing any firearms they own.30Everytown for Gun Safety, “More Than 8.5 Million Students Nationwide Will Attend Schools With Secure Firearm Storage Policies During Next School Year Following Passage of Orange County, Florida Resolution,” press release, December 15, 2022, https://www.everytown.org/press/more-than-8-5-million-students-nationwide-will-attend-schools-with-secure-firearm-storage-policies-during-next-school-year-following-passage-of-orange-county-florida-resolution/. Over the past few years, volunteers with Moms Demand Action and Students Demand Action, in partnership with Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, have successfully urged school boards across the country to enact such notification policies, including districts in Alaska,31Everytown for Gun Safety, “Following Tireless Advocacy from Alaska Moms Demand Action, Students Demand Action, Anchorage School Board Votes to Pass Historic Secure Storage Resolution,” press release, September 21, 2022, https://www.everytown.org/press/following-tireless-advocacy-from-alaska-moms-demand-action-students-demand-action-anchorage-school-board-votes-to-pass-historic-secure-storage-resolution%EF%BF%BC/. Arkansas,32Moms Demand Action, “Following Advocacy from Arkansas Moms Demand Action, Students Demand Action, Little Rock School Board Votes to Pass Secure Storage Resolution,” press release, September 23, 2022, https://momsdemandaction.org/following-advocacy-from-arkansas-moms-demand-action-students-demand-action-little-rock-school-board-votes-to-pass-secure-storage-resolution/. Arizona,33Moms Demand Action, “Arizona Moms Demand Action, Everytown Applaud the Unanimous Passage of Resolution to Require Phoenix Public Schools to Send Information Home About Secure Firearms Storage,” press release, February 7, 2020, https://momsdemandaction.org/arizona-moms-demand-action-everytown-applaud-the-unanimous-passage-of-resolution-to-require-phoenix-public-schools-to-send-information-home-about-secure-firearms-storage/. California, Colorado, Florida, Kentucky,34Everytown for Gun Safety, “Kentucky Moms Demand Action Applaud Unanimous Resolution to Distribute Secure Storage Information in Jefferson County Public Schools,” press release, February 8, 2023, https://www.everytown.org/press/kentucky-moms-demand-action-applaud-unanimous-resolution-to-distribute-secure-storage-information-in-jefferson-county-public-schools/. Massachusetts, Michigan,35Everytown for Gun Safety, “Southfield School District Passes Secure Storage Resolution Following Advocacy by Moms Demand Action Volunteers,” press release, February 9, 2022, https://www.everytown.org/press/southfield-school-district-passes-secure-storage-resolution-following-advocacy-by-moms-demand-action-volunteers/. Nevada, New Mexico,36Everytown for Gun Safety, “Major Milestone: More Than 90,000 New Mexico Students Now Attend Schools Requiring Secure Firearm Storage Notification,” press release, July 21, 2022, https://www.everytown.org/press/major-milestone-more-than-90000-new-mexico-students-now-attend-schools-requiring-secure-firearm-storage-notification/. Oregon, Texas,37Moms Demand Action, “Following Advocacy from Moms Demand Action, Students Demand Action Volunteers, Texas School Districts Educate Families About Secure Firearm Storage with the Help of Be SMART,” press release, October 4, 2022, https://momsdemandaction.org/following-advocacy-from-moms-demand-action-students-demand-action-volunteers-texas-school-districts-educate-families-about-secure-firearm-storage-with-the-help-of-be-smart/. Vermont,38Everytown for Gun Safety, “Vermont Moms Demand Action, Students Demand Action Applaud Champlain Valley School District for Sending Letter to all District Parents Regarding Secure Firearm Storage,” press release, May 19, 2021, https://www.everytown.org/press/vermont-moms-demand-action-students-demand-action-applauds-champlain-valley-school-district-for-passing-secure-firearm-storage-resolution/. Virginia, and Washington.39Everytown for Gun Safety, “Following Advocacy from Washington Moms Demand Action, Students Demand Action Volunteers, Spokane Public School District Passes Historic Secure Firearm Storage Resolution,” press release, October 31, 2022, https://www.everytown.org/press/following-advocacy-from-washington-moms-demand-action-students-demand-action-volunteers-spokane-public-school-district-passes-historic-secure-firearm-storage-resolution/. Action on secure storage can be taken at the state level too. Last year, following tireless advocacy from Moms Demand Action and Students Demand Action volunteers, California became the first state in the country to enact a statewide secure storage notification policy after Governor Newsom signed a law40CA SB 906 and AB 452 requiring public and charter schools to educate parents and caretakers about the critical role of secure firearm storage in keeping students safe from gun violence.41Everytown for Gun Safety, ”Following Tireless Advocacy by California Moms Demand Action, Students Demand Action, California Legislature Passes Groundbreaking Gun Violence Prevention Bills,” press release, August 9, 2022, https://www.everytown.org/press/following-tireless-advocacy-by-california-moms-demand-action-students-demand-action-california-legislature-passes-groundbreaking-gun-violence-prevention-bills/. This is a simple yet effective action that others can take to protect America’s students.42Students Demand Action, “Urge Your School Board to Act on School Safety,” January 26, 2022, https://studentsdemandaction.org/report/urge-your-school-board-to-act-on-school-safety/.

Too often, gun safety and secure storage practices aren’t part of the routine safety conversations pediatricians have with families. Prevention is really the cornerstone of our profession. We talk all the time about drowning prevention, chronic disease prevention, and motor vehicle crash injury prevention.

—Dr. Annie Andrews in conversation with Everytown for Gun Safety43Dr. Annie Andrews, MD, MSCR, associate professor in the Department of Pediatrics at the Medical University of South Carolina, in conversation with Kaelyn Forde, Everytown for Gun Safety, July 21, 2021.

Clinicians

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that pediatricians address firearm safety along with other safety precautions they routinely cover, such as the use of car seats, seat belts, and bike helmets, swimming pool safety, and locking up medications and household poisons. This includes asking parents about the presence of guns in the home and reminders about secure storage practices in their own homes and in any homes their children may visit.44Lois K. Lee et al., “Firearm-related Injuries and Deaths in Children and Youth: Injury Prevention and Harm Reduction,” Pediatrics 150, no. 6 (2022): e2022060070, https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2022-060070. Research on the impact of these conversations suggests that clinicians can influence secure storage practices among their patients, especially when they provide free storage devices.45RAND Corporation, “Education Campaigns and Clinical Interventions for Promoting Safe Storage,” March 2, 2018, https://bit.ly/2KPD71h.

Secure Gun Storage Laws

Educating gun owners and changing storage practices are necessary to protect children’s lives. However, given the scale of this challenge and the strength of the evidence in their favor, policies that hold adults accountable for failing to securely store their firearms are also a critical part of the solution.

There is currently no federal law requiring secure storage by gun owners. Federal law only requires gun dealers to provide a secure gun storage or gun safety device with the sale of every handgun. It does not require that gun owners actually use the device.

In the absence of federal policy, states have enacted a variety of gun storage-related laws, as outlined earlier.

The laws that research shows are most effective for preventing unintentional child shootings hold gun owners who fail to securely store firearms accountable if a child is likely to access an unsecured gun, or they stipulate that if a minor does access a firearm, the person who failed to adequately secure the firearm can be held liable.

Laws that punish only intentional or reckless provision of firearms to minors are not effective in protecting children; they should not be considered secure storage laws.

A 2020 study looking at the full range of child-access laws by state found a 59 percent reduction in unintentional firearm deaths among children ages 0 to 14 over the period 1991 to 2016 in the states with the most stringent child-access prevention laws. The authors also found that laws with liability only in the case of recklessness were not associated with reduced firearm deaths among this age group.46Hooman Alexander Azad et al., “Child Access Prevention Firearm Laws and Firearm Fatalities Among Children Aged 0 to 14 Years, 1991-2016,” JAMA Pediatrics 174, no. 5 (March 2, 2020): 463–69, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.6227. Another study focusing on children hospitalized for firearm injuries in 2006 and 2009 found a similar result: compared to states with no child-access laws, states with the strongest laws saw a 44 percent reduction in children hospitalized for firearm injuries related to unintentional shootings, most of them incidents at the hands of another child or of themself.47Emma C. Hamilton, “Variability Of Child Access Prevention Laws And Pediatric Firearm Injuries,” Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery 84, no. 4 (2018): 613–19, https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000001786. Finally, a 2013 study of nonfatal gun injury data in 11 states found that secure storage laws were associated with a 26 percent reduction in self-inflicted gun injuries among children under age 18.48Jeffrey DeSimone, Sara Markowitz, and Jing Xu, “Child Access Prevention Laws and Nonfatal Gun Injuries,” Southern Economic Journal 80, no. 1 (2013): 5–25, https://doi.org/10.4284/0038-4038-2011.333. One concern with these laws is that they tend not to be publicized widely enough after they are passed.49Ali Rowhani-Rahbar et al., “Knowledge of State Gun Laws among US Adults in Gun-owning Households,” JAMA Network Open 4, no. 11 (2021): e2135141, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.35141. While greater awareness would be ideal, a recent RAND study has suggested that one need not have direct knowledge of specific storage laws to be impacted by them—influencers in the broader gun-owning community contribute to changing the conversation around gun storage and impacting behaviors.50RAND Corporation, “The Effects of Child-Access Prevention Laws,” January 10, 2023, https://www.rand.org/research/gun-policy/analysis/child-access-prevention.html.

Our dataset on incidents over the past eight years backs up what research has found: states with the strongest laws related to preventing firearm access by children have the lowest rates of child shootings. Our analysis shows, depending on the type of law, rates of unintentional shootings by children were 34 to 78 percent lower in states with secure storage laws, compared to states without such laws.

Conclusion

Unintentional shootings by children are not an accident. They are a near-daily reality of life in America today. But they don’t have to be. They are almost always preventable with secure firearm storage practices, awareness, and policies.

Everytown has methodically tracked these incidents over eight years. We have learned that shootings by children are most often also shootings of children, that nearly a third of these shootings are by preschoolers who gained access to a loaded firearm, and that when children unintentionally shoot someone else the victim is most often a sibling or friend. We have also learned that nearly all of the over 2,800 incidents (97 percent) resulted in a single person being wounded or killed,51Of the 2,802 unintentional shooting incidents, 2,709 (96.7 percent) resulted in one person shot, 90 (3.2 percent) resulted in two people shot, and 3 (0.1 percent) resulted in three people shot. underscoring the fact that the child never meant to inflict casualties.

These realizations, plus our data on when and where the shootings occurred, help point to the times and places where prevention efforts need to focus. These shootings happened mostly in or around someone’s home and during times (weekends and summer) when children were most likely to be at home. But they also occurred in some states many times more than in others. The variation between states with the highest and lowest rates of shootings aligns with the strength of the laws holding gun owners accountable for storing their firearms securely in those states.

These avoidable tragedies cause physical and emotional suffering that persists far beyond the initial incident and leave scars on people far beyond the immediate families of those involved. And preventing them will require efforts from every sector of society. Gun owners must store all of their guns securely at all times; parents need to ask about guns and gun storage at any home their children will be visiting; schools, the medical community, gun shops and gun storage device sellers, and others play a vital role in educating the community about secure gun storage; and lawmakers and community members need to support laws that research has shown are effective in holding adults accountable for failing to store their firearms securely.

Acknowledgments

Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund would like to gratefully acknowledge Monika Goyal of Children’s National Hospital, Ali Rowhani-Rahbar of the University of Washington, and SGM (Ret.) P. Schoch of Everytown for Gun Safety’s Veterans Advisory Council, for their insightful reviews of the report, and Kaelyn Forde for report drafting and survivor interviews.

Everytown Research & Policy is a program of Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, an independent, non-partisan organization dedicated to understanding and reducing gun violence. Everytown Research & Policy works to do so by conducting methodologically rigorous research, supporting evidence-based policies, and communicating this knowledge to the American public.