Those Who Serve: Addressing Firearm Suicide Among Military Veterans

Executive Summary

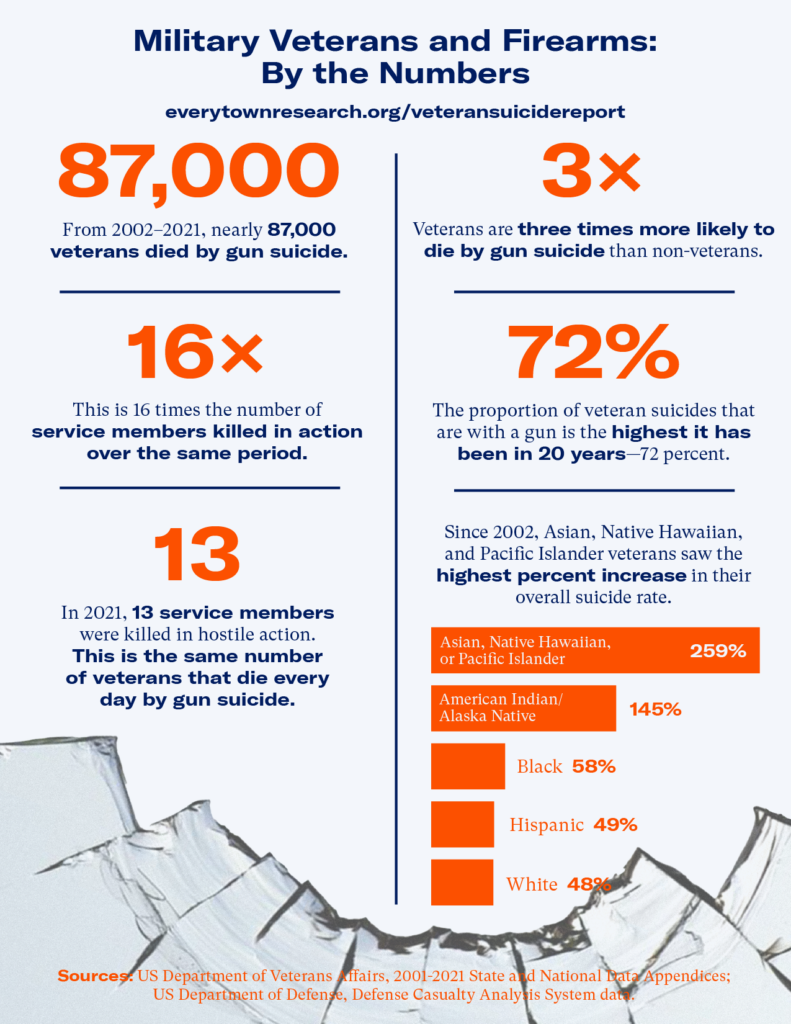

Beginning in 2020, the destabilizing impact of the COVID-19 pandemic led to social isolation, economic struggles, and worsening mental health across the country. Though suicide rates across the nation had declined from 2019 to 2020,1 Daniel C. Ehlman et al., “Changes in Suicide Rates—United States, 2019 and 2020,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 71, no. 8 (February 25, 2022): 306–12, http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7108a5. they began to increase in 2021, and veterans were not immune to this trend.2US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, 2023 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report (Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs, November 2023), https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2023/2023-National-Veteran-Suicide-Prevention-Annual-Report-FINAL-508.pdf. Veterans were defined as persons who had been activated for federal military service and were not currently serving at the time of their death. More veterans died by suicide in 2021 than in 2020,3Everytown Research analysis of US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, “2001–2021 National Data Appendix,” November 2023, https://bit.ly/2Qblicx. and studies show that veterans saw a higher incidence of mental health concerns during than before the pandemic.4Shaoli Li, Shu Huang, Shaohua Hu, and Jianbo Lai, “Psychological Consequences among Veterans during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Scoping Review,” Psychiatry Research 324 (June 2023): 115229, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2023.115229. By 2021, 72 percent of veteran suicides involved firearms—the highest proportion in over 20 years. With an average of 18 veterans dying by suicide in the United States each day, 13 of them by firearm, we cannot address veteran suicide without talking about guns.5Everytown Research analysis of US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, “2001–2021 State Data Appendix,” November 2023, https://bit.ly/2Qblicx. A yearly average was developed using five years of most recent available data: 2017 to 2021.

Veterans confront unique challenges during their service and face new ones when they return to civilian life. And these challenges are not always what might be expected. While many assume that suicide in veterans is associated with their time while deployed, in fact, veterans who served during the wars in Iraq in Afghanistan who were not deployed6Han K. Kang, Tim A. Bullman, Derek J. Smolenski, Nancy A. Skopp, Gregory A. Gahm, and Mark A. Reger, “Suicide Risk among 1.3 Million Veterans Who Were on Active Duty during the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars,” Annals of Epidemiology 25, no. 2 (February 2015): 96–100, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.11.020. Study determined deployment from the Defense Manpower Data Center Contingency Tracking System records of soldiers deployed to the war zones of Iraq or Afghanistan. had higher suicide rates than those who were deployed.

But one thing is clear: addressing the unique role guns play is an integral part of efforts to end veteran suicide.

It is crucial to pursue policies that can protect against veteran suicide, including disrupting a person’s access to a firearm when they are in crisis through secure gun storage, storing a gun outside the home, and using Extreme Risk laws; raising awareness about the risks of firearm access; addressing upstream factors that can lead to veteran suicide; and ensuring that we have timely data about the basic aspects of this crisis.

Key Findings

Veteran firearm suicide is an outsized part of a larger crisis.

In the United States, firearm suicide is a devastating public health crisis, claiming nearly 25,000 lives every year—about 68 deaths a day.8Everytown Research analysis of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. WONDER Online Database, Underlying Cause of Death. A yearly and daily average was developed using four years of the most recent available data: 2018 to 2021. The problem is not getting better: The firearm suicide rate has increased over the past decade.9Everytown Research analysis of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. WONDER Online Database, Underlying Cause of Death. A percent change was developed using 2012 and 2021 age-adjusted rates for all ages.

4,600

An average of 4,600 veterans die by firearm suicide every year.

Everytown Research analysis of US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, “2001–2021 State Data Appendix,” November 2023, https://bit.ly/2Qblicx. Five-year average: 2017–2021.

Veterans make up approximately one in five adult firearm suicides.10Everytown Research analysis of US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, “2001–2021 State Data Appendix,” November 2023, https://bit.ly/2Qblicx. A yearly average was developed using five years of most recent available data: 2017 to 2021. That averages to 4,600 veteran firearm suicides every year.11Everytown Research analysis of US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, “2001–2021 State Data Appendix,” November 2023, https://bit.ly/2Qblicx. A yearly average was developed using five years of most recent available data: 2017 to 2021. Over the past 20 years, the veteran firearm suicide rate has increased by 51 percent. The firearm suicide rate among non-veteran adults increased 32 percent over this same period.12Everytown Research analysis of US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, “2001–2021 State Data Appendix,” November 2023, https://bit.ly/2Qblicx. Veteran firearm suicide crude rates were calculated using veteran population estimates provided by the VA in the “2001–2021 National Data Appendix,” https://bit.ly/2Qblicx. Percent change: 2002 vs. 2021. The rate increased from 16.3 veteran firearm suicides per 100,000 people in 2002 to 24.5 per 100,000 in 2021—a 51 percent increase. The non-veteran adult firearm suicide rate increased from 6.6 per 100,000 in 2002 to 8.7 per 100,000 in 2021—a 32 percent increase.

The veteran suicide rate increased 51 percent since 2002.

Last updated: 2.1.2024

Gun ownership increases the likelihood of firearm suicide, and suicide attempts with firearms are nearly always lethal.

The dynamics of suicide are complex. However, research has confirmed that a combination of risk factors are often present before a suicide attempt. These known risk factors are (1) current life stressors, such as relationship problems, unemployment or financial problems, bullying, alcohol and substance use disorders, or mental health conditions, (2) historical risk factors, such as childhood abuse or trauma, a previous suicide attempt, or a family history of suicide, and (3) access to lethal means of harm such as firearms.13American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, “Risk Factors, Protective Factors, and Warning Signs,” accessed December 1, 2023, https://afsp.org/risk-factors-protective-factors-and-warning-signs/. Suicide risk dramatically increases when these factors coincide to create a sense of hopelessness and despair.

But one thing is clear: Easy access to firearms during a moment of crisis can mean the difference between life and death. Personal or household gun ownership triples the suicide risk.14Andrew Anglemyer, Tara Horvath, and George Rutherford, “The Accessibility of Firearms and Risk for Suicide and Homicide Victimization Among Household Members: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” Annals of Internal Medicine 160, no. 2 (2014): 101–10, https://doi.org/10.7326/M13-1301. Firearms are a particularly lethal means of self-harm,15Andrew Conner, Deborah Azrael, and Matthew Miller, “Suicide Case-Fatality Rates in the United States, 2007 to 2014: A Nationwide Population-Based Study,” Annals of Internal Medicine 171, no. 12 (2019): 885–95. and most people who survive a suicide attempt do not go on to die by suicide.16Robert Carroll, Chris Metcalfe, and David Gunnell, “Hospital Presenting Self-Harm and Risk of Fatal and Non-Fatal Repetition: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” PLOS ONE 9, no. 2 (February 28, 2014): e89944, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0089944; David Owens, Judith Horrocks, and Allan House, “Fatal and Non-fatal Repetition of Self-Harm: Systematic Review,” British Journal of Psychiatry 181, no. 3 (September 2002): 193–99, https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.181.3.193. Limiting gun access in a moment of acute crisis can ensure veterans live on as valued and valuable community members.

Veterans are more likely to own guns than non-veterans and are more likely to die by firearm suicide.

Across all suicide methods used, veterans suffer a higher suicide rate compared to non-veterans. But firearms—the most lethal among commonly used methods of self-harm—are the prevailing method among veterans who die by suicide.17US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, 2023 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report (Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs, November 2023), https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2023/2023-National-Veteran-Suicide-Prevention-Annual-Report-FINAL-508.pdf. Half of veterans report owning guns (compared to 20 percent of non-veterans),18Nichter, Brandon, Melanie L. Hill, Ian Fischer, Kaitlyn E. Panza, Alexander C. Kline, Peter J. Na, Sonya B. Norman, Mara Rowcliffe, and Robert H. Pietrzak. “Firearm Storage Practices among Military Veterans in the United States: Findings from a Nationally Representative Survey.” Journal of Affective Disorders 351 (April 2024): 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2024.01.179. Deborah Azrael et al., “The Stock and Flow of US Firearms: Results from the 2015 National Firearms Survey,” RSF: The Russell Sage Foundation Journal of the Social Sciences 3, no. 5 (October 2017): 38–57. and in 2021, veterans were nearly three times more likely than non-veterans to die by gun suicide.19Everytown Research analysis of US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, “2001–2021 National Data Appendix,” November 2023, https://bit.ly/2Qblicx. Veteran and non-veteran crude rates for 2021. In fact, the use of guns in veteran suicide is becoming more frequent; in 2021, 72 percent of veteran suicides were by gun—the highest proportion in 20 years.20Everytown Research analysis of US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, “2001–2021 State Data Appendix,” November 2023, https://bit.ly/2Qblicx. The prevalence of firearm use among veterans means an already urgent crisis is that much more lethal.

Firearms are the prevailing method of suicide among veterans.

Last updated: 2.1.2024

Firearms are increasingly used in suicides among female veterans.

Firearm suicide makes up a smaller proportion of all suicide deaths among female veterans than among males (52 percent and 73 percent, respectively, in 2021), but that is changing.21US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, 2023 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report (Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs, November 2023), bit.ly/42Cu9Zt; US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, “Suicide among Veterans and Other Americans, 2001–2014,” August 2017, https://tinyurl.com/284seurc. Compared to other suicide methods, the use of firearms in female veteran suicide is increasing faster than among their male counterparts. From 200122Note: 2001 data is used for comparison because the proportion of suicide deaths by firearms by gender in 2002 has not been published by the Department of Veterans Affairs. to 2021, the proportion of suicide deaths by firearm increased 42 percent among female veterans but 9 percent among male veterans.23Everytown Research analysis of US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, 2023 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report (Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs, November 2023), bit.ly/42Cu9Zt; and US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, “Suicide among Veterans and Other Americans, 2001–2014,” August 2017, https://tinyurl.com/284seurc. In addition, female veterans are more likely than civilian women to use a gun to die by suicide—in 2021, the firearm suicide rate among veteran women was nearly three times higher than among non-veteran women.24US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, 2023 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report (Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs, November 2023), bit.ly/42Cu9Zt. This trend is consequential because women are the fastest-growing veteran group, currently comprising about 11 percent of the US veteran population.25Everytown Research analysis of US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, “2001–2021 National Data Appendix,” November 2023, https://bit.ly/2Qblicx.

Veteran suicide is rising among all races and ethnicities.

By sheer numbers, the vast majority of veterans who die by suicide are white, as is also the case in the general US population. Rates, however, tell another story. The highest suicide rates per 100,000 veterans in 2021 were seen in American Indian and Alaska Native veterans, followed by white veterans and Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander veterans.26Due to a lack of method-specific data by both race and ethnicity and age groupings, analysis for these demographic groups is presented for overall suicide. When looking at change in overall suicide over the past two decades, the data clearly shows that rates are rising among veterans of all races and ethnicities, although the burden is not felt equally. While suicide by all methods has gone up, some groups are seeing starker increases than others.27Everytown Research analysis of US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, “2001–2021 National Data Appendix,” November 2023, https://bit.ly/2Qblicx. Since 2002, this increase has been especially sharp among two groups: American Indian and Alaska Native veterans, who have had a 145 percent increase in their suicide rate, and Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander veterans, who have had a 259 percent increase.

Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander veterans have seen the highest suicide rate increases

Last updated: 2.1.2024

How do these increases compare to racial and ethnic increases in suicide in the general public? For both veterans and the general population, the suicide rate has increased for all racial and ethnic groups. But these increases are especially stark for veterans. For example, among the general population, American Indian and Alaska Native people experienced the highest rate increase since 2002: a 68 percent increase. Only Black veterans saw the same suicide increase as in the general population (58 percent). In all other groups, the veteran rate increase outpaced that of the general population. This is especially so for Asian, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander veterans, who saw one of the lowest increases in the general population (30 percent) but the highest among veterans (259 percent).28Everytown Research analysis of US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, “2001–2021 National Data Appendix,” November 2023, https://bit.ly/2Qblicx.

The veteran suicide rate is highest among 18- to 34-year-olds.

In 2002, the highest suicide rate was seen among veterans aged 35 to 54, an age group made up of veterans who served at the same time as conflicts in Vietnam (1962–1973), the Persian Gulf (1991), and the intervening years.29U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. “Veterans Employment Toolkit: Dates and Names of Conflicts.” Accessed January 25, 2024. https://www.va.gov/vetsinworkplace/docs/em_datesnames.asp. Twenty years later, the suicide rate has increased among the youngest veterans, and veterans aged 18 to 34 now have the highest rate of suicide. In fact, in 2021, the rate of suicide among this age group was 37 percent higher than the rate of suicide among veterans overall.30Everytown Research analysis of US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, “2001–2021 National Data Appendix,” November 2023, https://bit.ly/2Qblicx. Among both men and women, the youngest veterans are facing the highest burden. This younger cohort of veterans began service in the post-9/11 era, and some of the youngest veterans hadn’t even been born when the conflict began.

Veteran suicide is not always the result of combat trauma.

It is commonly assumed that suicide risk in veterans is due in large part to exposure to traumatic incidents while deployed to combat, but in fact, among veterans who served during the Iraq and Afghanistan wars, those who were not deployed to the Iraq or Afghanistan war zones were actually at higher risk for suicide than those who were.31Han K. Kang, Tim A. Bullman, Derek J. Smolenski, Nancy A. Skopp, Gregory A. Gahm, and Mark A. Reger, “Suicide Risk among 1.3 Million Veterans Who Were on Active Duty during the Iraq and Afghanistan Wars,” Annals of Epidemiology 25, no. 2 (February 2015): 96–100, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.11.020. Combat trauma has a complex relationship with suicide risk among veterans, and while research shows that certain conditions like post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) can contribute to suicide risk, there is no clear association between combat exposure generally and the risk of dying by suicide.32William Hudenko, Beeta Homaifar, and Hal Wortzel, “The Relationship Between PTSD and Suicide,” National Center for PTSD, US Department of Veterans Affairs, https://www.ptsd.va.gov/professional/treat/cooccurring/suicide_ptsd.asp#two.

It is not entirely clear what drives this noteworthy difference, though some evidence suggests it is due to the “healthy warrior effect,” where soldiers are screened for their psychological resilience early in their careers. Recruits are trained in an intense environment that may reveal traits or disorders ill-suited for a war zone, which is a consideration for deployment later in their careers. One study of marines deployed in Iraq and Afghanistan found that all psychiatric conditions except PTSD occurred at higher rates in non-deployed soldiers, suggesting that resilience is observed before deployment.33Gerald E. Larson, Robyn M. Highfill-McRoy, and Stephanie Booth-Kewley, “Psychiatric Diagnoses in Historic and Contemporary Military Cohorts: Combat Deployment and the Healthy Warrior Effect,” American Journal of Epidemiology 167, no. 11 (June 1, 2008): 1269–76, https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwn084. Since veterans with mental health diagnoses have a higher suicide rate, such resilience may be an important protective factor.34US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, 2023 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report (Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs, November 2023), bit.ly/42Cu9Zt.

Additionally, aspects of being in the military separate from combat exposure can contribute to a veteran’s suicide risk. Military service can provide soldiers with positive experiences and skills, such as leadership, decision-making, working with a team, and commitment.35James Craig, Jeanette Leonard, Ronald Link, and Tammy White-McKnight, “Understanding Military Culture: A Primer in Cultural Competence Working with Military Members and Families,” Health Services Research & Development, US Department of Veterans Affairs, Washington, DC, video, April 5, 2022, https://www.hsrd.research.va.gov/for_researchers/understanding-military-culture.cfm. But the culture that leads to success in the military, prizing discipline, group needs, and close bonds with other soldiers, may be lacking in US society when a soldier then transitions to become a veteran. Physical conditions that may result from military service can prove challenging as well; chronic pain, sleeplessness, increased health problems, and decreased physical ability are all risk factors for suicide.36US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention, 2023 National Veteran Suicide Prevention Annual Report (Washington, DC: US Department of Veterans Affairs, November 2023), bit.ly/42Cu9Zt. Research shows that without support, veterans risk feeling disoriented and without identity or meaning when they transition to civilian life.37Pease, James L., Melodi Billera, and Georgia Gerard. “Military Culture and the Transition to Civilian Life: Suicide Risk and Other Considerations.” Social Work 61, no. 1 (January 1, 2016): 83–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swv050.

Recommendations

The following are recommendations that research shows are effective in reducing suicide for all people. While more research is urgently needed to determine the effectiveness of veteran-specific suicide prevention and intervention, the policies below can also be used to address the rising rates of suicide among veterans as well as the general public.

We need to promote practices that put time and distance between those contemplating suicide and their guns.

Veterans are more likely to own firearms than non-veterans, and the average firearms-owning veteran owns six guns.38Emily C. Cleveland et al., “Firearm Ownership among American Veterans: Findings from the 2015 National Firearm Survey,” Injury Epidemiology 4, no. 33 (December 2017), doi: 10.1186/s40621-017-0130-y. Secure gun storage practices, one foundational intervention point, are likely familiar to military service members and veterans, as military-issued guns are required to be stored in certain ways.

53%

53 percent of veteran gun owners do not store all of their guns securely.

Nichter, Brandon, Melanie L. Hill, Ian Fischer, Kaitlyn E. Panza, Alexander C. Kline, Peter J. Na, Sonya B. Norman, Mara Rowcliffe, and Robert H. Pietrzak. “Firearm Storage Practices among Military Veterans in the United States: Findings from a Nationally Representative Survey.” Journal of Affective Disorders 351 (April 2024): 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2024.01.179.

Last updated: 2.1.2024

However, personal weapons may be treated differently: A 2022 survey found that while half of veterans own guns, the majority do not store all their guns securely.39Brandon Nichter et al., “Firearm Storage Practices among Military Veterans in the United States: Findings from a Nationally Representative Survey,” Journal of Affective Disorders 351 (April 2024): 82–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2024.01.179. In fact, veterans with certain risk factors for suicide—including alcohol misuse, depression, and suicidal ideation—were more likely to store their guns insecurely. Encouraging veterans to treat personal weapons with the same focus on safety expected while in the military is just one way we can prevent gun suicides in military communities.

Suicidal crises are often very brief, and preventing access to lethal means can stop a moment of despair from becoming an irreversible tragedy. Methods to reduce gun access for those in crisis exist on a continuum, and depending on the circumstances, some interventions may be more effective than others. If one tactic is not successful, another intervention can be used to put time and space between a person contemplating suicide and a particularly lethal means. Under this continuum, in addition to securely storing firearms at home, veterans with firearms in their homes can work with friends, family members, or physicians to give the keys to the person’s secure storage device to a trusted friend or family member, put a plan in place to temporarily store their firearms with a friend or relative or in a storage facility, and/or take action to limit their own ability to acquire new guns in times of crisis. Voluntary Do Not Buy lists (sometimes called Voluntary Prohibition lists), currently enacted in several states, enable people to put themselves on a list that temporarily prevents them from purchasing guns.40See, e.g., Rev. Code Wash. (ARCW) § 9.41.350; Va. Code Ann. § 52-50, et. seq.; Utah Code Ann. § 53-5c-301. Firearm storage maps have been developed to help community members find third-party storage options in several states and localities, including Colorado, Maryland, Mississippi, New Jersey, New York, and Washington State. Education about the ways to disrupt a person’s access to a gun when they are in crisis is an important part of preventing suicide.

We need to identify veterans in crisis, and ensure all 50 states have the authority to temporarily remove their access to firearms.

Extreme Risk laws, sometimes referred to as “red flag” laws, allow immediate family members and/or law enforcement to petition a civil court for an order to temporarily remove guns during times of crisis. A growing number of states and Washington, DC, have adopted this effective suicide intervention tool.41Aaron J. Kivisto and Peter Lee Phalen, “Effects of Risk-Based Firearm Seizure Laws in Connecticut and Indiana on Suicide Rates, 1981-2015,” Psychiatric Services 69, no. 8 (June 2018): 855–62; Jeffrey W. Swanson et al., “Implementation and Effectiveness of Connecticut’s Risk-Based Gun Removal Law: Does It Prevent Suicides?” Law and Contemporary Problems 80, no. 2 (2017): 179–208; Jeffrey W. Swanson et al., “Criminal Justice and Suicide Outcomes with Indiana’s Risk-Based Gun Seizure Law,” Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 47, no. 3 (April 2019): 188–97. Risk-mitigation planning is critical to preventing suicide. For veterans’ families and friends, this plan can include steps to intervene by utilizing these laws. If a court finds that a person poses a serious risk of injuring themselves or others with a firearm, that person becomes temporarily prohibited from purchasing and possessing guns, and any guns they already own must be turned in and held by law enforcement or another authorized party while the order is in effect.

Extreme Risk Law

21 states have adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Alabama has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Alaska has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Arizona has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Arkansas has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

California has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement, immediate family members, employers, coworkers, teachers, roommates, people with a child in common or who have a dating relationship

Extreme Risk Law

Colorado has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement, family/household members, certain medical professionals, and certain educators

Extreme Risk Law

Connecticut has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement, family/household members, and medical professionals

Extreme Risk Law

Delaware has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement and family members

Extreme Risk Law

Florida has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement only

Extreme Risk Law

Georgia has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Hawaii has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement, family/household members, medical professionals, educators, and colleagues

Extreme Risk Law

Idaho has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Illinois has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement and family members

Extreme Risk Law

Indiana has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement only

Extreme Risk Law

Iowa has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Kansas has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Kentucky has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Louisiana has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Maine has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Maryland has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement, family members, doctors, and mental health professionals

Extreme Risk Law

Massachusetts has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Family/household members and gun licensing authorities

Extreme Risk Law

Michigan has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement, family/household members, certain health care providers

Extreme Risk Law

Minnesota has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement and family members

Extreme Risk Law

Mississippi has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Missouri has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Montana has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Nebraska has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Nevada has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement and family/household members

Extreme Risk Law

New Hampshire has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

New Jersey has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement and family/household members

Extreme Risk Law

New Mexico has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement only

Extreme Risk Law

New York has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement, district attorneys, family/household members, school administrators, certain medical professionals

Extreme Risk Law

North Carolina has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

North Dakota has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Ohio has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Oklahoma has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Oregon has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement and family/household members

Extreme Risk Law

Pennsylvania has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Rhode Island has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement only

Extreme Risk Law

South Carolina has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

South Dakota has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Tennessee has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Texas has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Utah has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Vermont has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- States attorneys and the Office of the Attorney General; family/household members

Extreme Risk Law

Virginia has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement and Commonwealth Attorneys

Extreme Risk Law

Washington has adopted this policy

- Who may petition for an order?

- Law enforcement and family/household members

Extreme Risk Law

West Virginia has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Wisconsin has not adopted this policy

Extreme Risk Law

Wyoming has not adopted this policy

While not all veterans seek Veterans Health Administration (VHA) services, the agency can, when not in conflict with patient confidentiality, work with designated petitioners to protect at-risk veterans by temporarily preventing their access to firearms. Extreme Risk laws have been proven to reduce firearm suicides. Following Connecticut’s increased enforcement of its Extreme Risk law, one study found the law to be associated with a 14 percent reduction in the state’s firearm suicide rate. And in Indiana, in the 10 years after the state passed its Extreme Risk law in 2005, the state’s firearm suicide rate decreased by 7.5 percent.42Aaron J. Kivisto and Peter Lee Phalen, “Effects of Risk-Based Firearm Seizure Laws in Connecticut and Indiana on Suicide Rates, 1981-2015,” Psychiatric Services 69, no. 8 (June 2018): 855–62. Warning signs that someone is suicidal are often most apparent to household or family members, and while it can sometimes feel like there is nothing that can be done, requesting an Extreme Risk Protection Order is one thing people can do.

We need healthcare professionals to have conversations about gun access and suicide risk.

2/3

Roughly two in three Americans who attempt suicide will visit a healthcare professional in the month before the attempt.

Ahmedani, B. K. et al. “Racial/Ethnic differences in health care visits made before suicide attempt across the United States”. Medical Care. (2019). https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000335

Roughly two in three Americans who attempt suicide will visit a healthcare professional in the month before the attempt.43Brian Ahmedani et al., “Racial/Ethnic Differences in Health Care Visits Made before Suicide Attempt across the United States,” Medical Care 53, no. 5 (May 2015): 430–35. One survey of veterans already receiving mental health care found that more than half (56 percent) of patients with a suicide plan had guns in the household.44Marcia Valenstein et al., “Possession of Household Firearms and Firearm-Related Discussions with Clinicians among Veterans Receiving VA Mental Health Care,” Archives of Suicide Research 24, no. sup1 (February 2019), doi: 10.1080/13811118.2019.1572555. These visits offer critical opportunities for conversations about firearm access.

Counseling for Access to Lethal Means (CALM) is one program designed to equip medical professionals with language for discussing this risk with their patients, and it has been offered by some VHA facilities. Providers who have received this training are more likely to counsel clients on the importance of restricting access to lethal means of suicide. One study found that after receiving training, 65 percent of mental health care providers counseled on access to lethal means.45Renee M. Johnson et al., “Training Mental Healthcare Providers to Reduce At-Risk Patients’ Access to Lethal Means of Suicide: Evaluation of the CALM Project,” Archives of Suicide Research 15, no. 3 (August 2011): 259–64. And while these conversations may be challenging, a majority of US gun owners, including veterans, agree that it is appropriate for clinicians to talk about firearm safety with their patients.46Marian E. Betz et al., “Public Opinion Regarding Whether Speaking with Patients about Firearms Is Appropriate: Results of a National Survey,” Annals of Internal Medicine 165, no. 8 (October 2016): 543–50. These conversations could save lives.

We need greater public and veteran awareness about the inherent risks of firearm access.

Many Americans are unaware of the threat firearms in the home can pose with respect to suicide. Access to a firearm increases the suicide risk three-fold for all household members.47Andrew Anglemyer, Tara Horvath, and George Rutherford, “The Accessibility of Firearms and Risk for Suicide and Homicide Victimization among Household Members: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” Annals of Internal Medicine 160, no. 2 (January 2014): 101–110. As discussed, veterans are far more likely to own firearms than non-veterans, and a majority (63 percent) cite protection as a primary reason for firearm ownership.48Emily C. Cleveland et al., “Firearm Ownership among American Veterans: Findings from the 2015 National Firearm Survey,” Injury Epidemiology 4, no. 33 (December 2017), doi: 10.1186/s40621-017-0130-y; Andrew Anglemyer, Tara Horvath, and George Rutherford, “The Accessibility of Firearms and Risk for Suicide and Homicide Victimization among Household Members: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” Annals of Internal Medicine 160, no. 2 (January 2014): 101–110. But only 6 percent of veterans agree that having a gun in the home is a suicide risk factor.49Joseph A. Simonetti et al., “Firearm Storage Practices among American Veterans,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 55, no. 4 (October 2018): 445–54.

As service members transition into becoming veterans, both the Department of Veterans Affairs and the Department of Defense are in a unique position to inform them of the risks of firearm ownership as a civilian. The Transition Assistance Program, which is mandatory for most people separating from the military, provides information and resources to prepare service members to become civilians. Alongside providing transitional support, training for the workforce, and an explanation of veteran benefits, this program provides an important opportunity for trusted messengers to share information about the risks and best practices of owning a firearm as a civilian.

Building public awareness about the inherent dangers of firearm access may help gun-owning veterans or their families to mitigate risks. For example, there are a number of innovative programs across the country that bring suicide prevention information directly to gun owners. These include a partnership between suicide prevention and firearm safety organizations to bring mandatory training sessions to those seeking concealed-carry permits in Utah.50Utah Bureau of Criminal Information, “Firearm Suicide Prevention: A Brief Module for Utah Concealed Carry Class,” 2016, https://bci.utah.gov/wp-content/uploads/sites/15/2019/05/Firearm-Safety-PPT-UT-FINAL.pdf. Likewise, the Gun Shop Project in New Hampshire, which provides suicide prevention literature at firearm retailers, has expanded to several other states.51The Connect Program,“NH Firearm Safety Coalition – Suicide Prevention: A Role for Firearm Dealers and Ranges,” accessed December 13, 2023, https://theconnectprogram.org/resources/nh-firearm-safety-coalition/; Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, “Means Matter: Gun Shop Project,” https://bit.ly/2c4QKah. Although some research demonstrates the impact of the Gun Shop Project in New Hampshire, rigorous evaluations of training programs for firearm purchasers and public awareness campaigns are needed to provide further information on their efficacy, particularly among veterans.

We need to address upstream factors to understand and prevent veteran gun suicide.

To prevent firearm suicide, it is crucial to recognize intervention points before an attempt. In its 2021 report entitled Reducing Military and Veteran Suicide: Advancing a Comprehensive, Cross-Sector, Evidence-Based Public Health Strategy, the Biden-Harris administration named addressing upstream risk and protective factors as a priority in preventing suicide among veterans. Barriers to accessing healthcare and benefits, financial and housing insecurity, difficulties in transitioning to civilian life, and job insecurity can all contribute to suicide risk.52The White House, Reducing Military and Veteran Suicide: Advancing a Comprehensive, Cross-Section, Evidence-Informed Public Health Strategy (Washington, DC: The White House, November 2021), https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/Military-and-Veteran-Suicide-Prevention-Strategy.pdf. Policies to address these challenges and support veterans in navigating them are an important part of a holistic approach to preventing suicide.

We need timely data about veteran suicide and more research on the effectiveness of existing initiatives to combat this crisis.

Veteran suicide is an urgent, worsening crisis, but the lack of timely information about even the most basic aspects of this problem makes it difficult to design effective interventions. Data from 2021, the most recent year available, shows that veteran suicide was exacerbated by the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic. Now, years later, it is important to see how these trends and impacts have changed. Yet public access to that data is likely two to three years away. Knowing what challenges are facing today’s veterans is crucial to alleviating them and ultimately preventing suicide.

Additionally, it is important to study different programs dedicated to preventing veteran suicide to reveal which ones are effective. The Department of Veterans Affairs facilitates many initiatives dedicated to ending veteran suicide, such as community-based outreach, expanding crisis line and telehealth options for veterans considering suicide, and peer support services. Evaluating these programs is a critical step toward revealing which are most effective in preventing veteran suicide.

Conclusion: Better Supporting Those Who Serve

To truly honor those who serve, we must fully support the strategies and additional research necessary to prevent veteran firearm suicide. Veterans are more likely than the general population to die by suicide, and more often use a gun. And too many don’t store their guns safely, so there is no barrier between themselves and a particularly lethal means of self-harm. Addressing the rising rates of veteran suicide requires acknowledging the importance of guns in this crisis.

Veterans deserve the best resources our country can offer. The recommendations outlined above are just the start of a larger dialogue on effective strategies to give back to those who serve.

Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund would like to gratefully acknowledge members of the Everytown Veterans Advisory Council: Amber Schleuning, Kayla Williams, Mike Jason, Everytown Veteran Lead Chris Marvin, and The Heinz Endowments Director of Veterans Affairs Megan Andros, for sharing their invaluable expertise during the drafting of this report.

Support for those in crisis

If you are a veteran in crisis—or you’re concerned about one—free, confidential support is available 24/7. Call the Veterans Crisis Line at 988 and press 1, text 838255, or chat online at veteranscrisisline.net.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, please call or text 988, or visit 988lifeline.org/chat to chat with a counselor from the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline, previously known as the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline. The 988 Lifeline provides free 24/7 confidential support to people in suicidal crisis or emotional distress anywhere in the US.

Everytown Research & Policy is a program of Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, an independent, non-partisan organization dedicated to understanding and reducing gun violence. Everytown Research & Policy works to do so by conducting methodologically rigorous research, supporting evidence-based policies, and communicating this knowledge to the American public.