Too Many, Too Soon: Youth Firearm Suicide in the United States

Last Updated: 8.25.2025

Executive Summary

Content Warning: This report aims to increase readers’ understanding of suicide, particularly by firearm, among young people in the United States. If you or someone you know is in a time of crisis or needs to talk to someone, please call or text the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline at 988 free from anywhere in the US. See additional resources at the end of the report.

“In the blink of an eye, my whole life changed.” My son, Ty-Key, wrote these lyrics—searching for the words to express the loss of his best friend, Keondrick, who was shot and killed. Ty-Key survived that shooting, but five years later, at age 22, he took his own life with a gun. Ty-Key was always doing things. He was a football player, rapper, and the cool guy on the block. He was smart, too—he even had the opportunity to skip a grade. People knew him. People loved him—they always had. I miss him every day. In response to my son’s suicide, I have dedicated my life to preventing gun suicide, and providing grief counseling to help others find healing, because I want other young people to know that they can find help and there is hope.

Miami Knight, Ty-Key’s mom and a gun violence prevention advocate Read more at Moments That Survive.

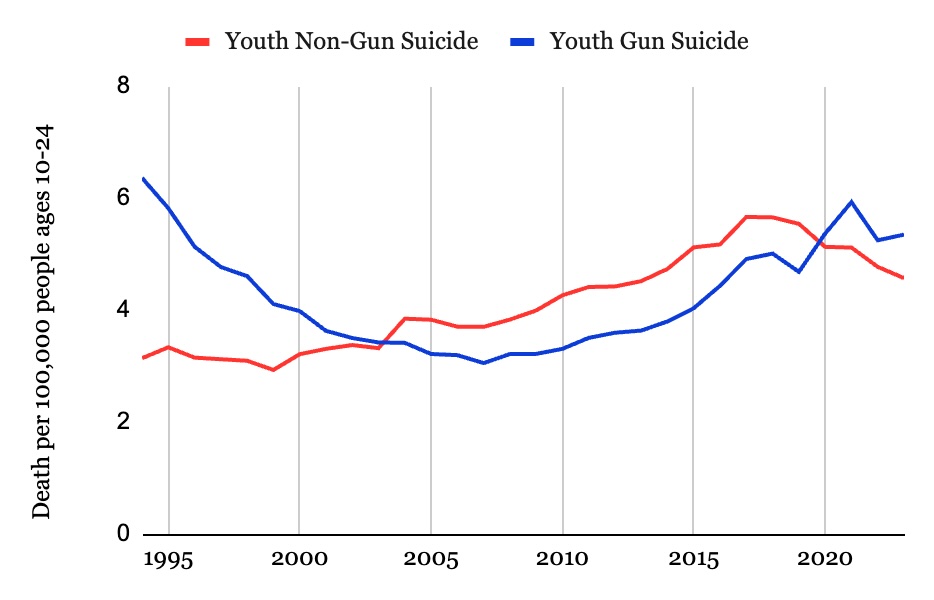

Firearm suicide is a devastating crisis in the United States, with rates averaging nearly 12 times greater than other high-income countries.1Everytown Research analysis of the most recent years of gun suicides by country (2015 to 2019), GunPolicy.org (accessed January 7, 2022). Tragically, young people are not spared: Over the past decade, firearm suicide rates increased over 40 percent for young people ages 10 to 24—more than most other age groups.2Everytown Research analysis of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, WONDER online database, Underlying Cause of Death. Based on percentage change in crude rates: 2014 vs. 2023. Crude rates for young people (ages 10–24) and 10-year age groupings from 25–64, and 65+. The age group of 25–34 experienced a higher increase at 43 percent in comparison to the age group of 10–24 at 41 percent. There is no single cause of suicide, and contributing factors can stem from the individual, relationship, community, and societal levels.3Developmental psychologist Urie Bronfenbrenner originally theorized an ecological model to examine human development. See Urie Bronfenbrenner, “Ecological Systems Theory,” in Encyclopedia of Psychology, ed. Alan E. Kazdin (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000), 3:129–133, http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/10518-046. Researchers continue to seek explanations for what is behind this alarming rise in firearm suicide in the United States and are examining the lingering impacts of COVID-19,4Sherry Everett Jones et al., “Mental Health, Suicidality, and Connectedness among High School Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Adolescent Behaviors and Experiences Survey, United States, January–June 2021,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Supplement 71, no. 3 (2022): 16–21, https://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su7103a3. anxiety and depression,5Jean M. Twenge et al., “Increases in Depressive Symptoms, Suicide-Related Outcomes, and Suicide Rates among US Adolescents after 2010 and Links to Increased New Media Screen Time,” Clinical Psychological Science 6, no. 1 (2017): 3–17, https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702617723376. social media use,6Rosemary Sedgwick et al., “Social Media, Internet Use and Suicide Attempts in Adolescents,” Current Opinion in Psychiatry 32, no. 6 (2019): 534–41, https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000547. cyberbullying,7Sameer Hinduja and Justin W. Patchin, “Connecting Adolescent Suicide to the Severity of Bullying and Cyberbullying,” Journal of School Violence 18, no. 3 (2019): 333–46, https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2018.1492417. and stigma about seeking help,8Cate Curtis, “Youth Perceptions of Suicide and Help-Seeking: ‘They’d Think I Was Weak or “Mental,”’ ” Journal of Youth Studies 13, no. 6 (2010): 699–715, https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261003801747. as well as the country’s recent and unprecedented surge in gun sales.9Matthew Miller, Wilson Zhang, and Deborah Azrael, “Firearm Purchasing during the COVID-19 Pandemic: Results from the 2021 National Firearms Survey,” Annals of Internal Medicine 175, no. 2 (2022); 219–25, https://doi.org/10.7326/M21-3423.

Despite this complexity, we can help prevent suicide, including firearm suicide. Removing access to firearms—a uniquely lethal means—from individuals at-risk for suicide, is the quickest and most effective intervention. We can save lives by implementing policies that limit easy and immediate access to firearms, increasing awareness of suicide risk factors, normalizing conversations about mental health, improving access to culturally appropriate mental health care, and supporting young people.

-

KEY FINDINGS

- Each year, over 3,400 young people (ages 10 to 24) die by firearm suicide—an average of nine people each day.

- Over the past decade, the rate of firearm suicide among young people has increased over 40 percent—more than most other age groups.

- In 2020, youth suicides involving a gun surpassed those by all other methods, including suffocation and poisoning.

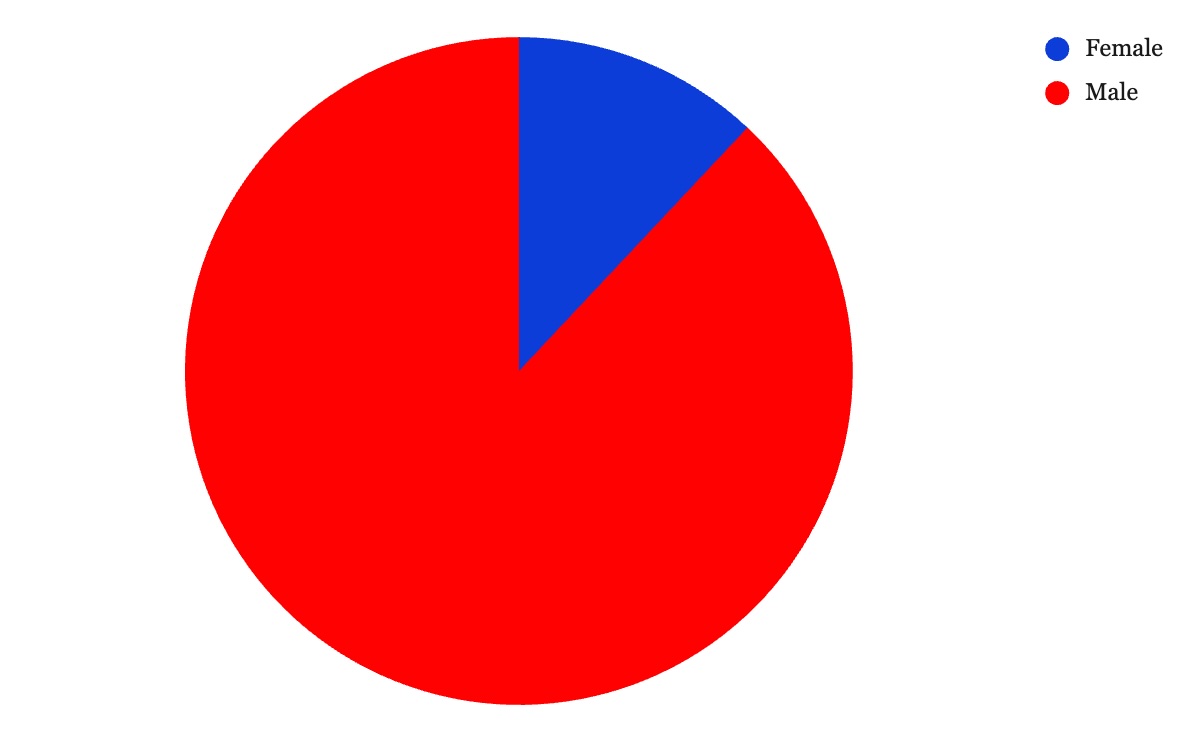

- Boys and young men represent nearly nine in 10 youth firearm suicide victims.

- Young American Indians and Alaska Natives (AIANs) have the highest firearm suicide rate on average—more than four times greater than the group with the lowest rate.

- Black youth experienced a nearly 160 percent increase in their firearm suicide rate over the past decade, followed by Latinx and Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (ANHPI) youth, who had increases of 111 and 84 percent, respectively.

- In 2022, for the first time since data became available in 1968, Black youth were more likely to die from gun suicide than white youth.

Introduction

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among young people (ages 10–24) in the United States1Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death, Leading Causes of Death, 2023. Ages 10–24. and the rate has increased most years since 2007.2Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death. Crude rates: 2007–2023. Ages 10–24. Meanwhile, the homicide rate among young people is nearly the same as it was then, and adult suicide rates rose at a slower rate.3 Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death, 2007–2023. Crude rates for young people (ages 10–24) and adults (ages 25 and older). Homicides include shootings by police.

The landscape of youth suicide has also changed: In 2020, for the first time in nearly 20 years, the proportion of youth suicides that involved a gun surpassed those by all other methods including hanging and drug overdose, and the use of firearms continues to be higher.4Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death. Crude rates: 1968–2023. Ages 10–24. After reaching a nearly 30-year high in 2021, the youth firearm suicide rate fell by 12 percent in 2022, and rose by 2 percent in 2023, but it still remains unacceptably high.5Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death. Crude rates: 1979–2023. Ages 10–24. In 2021 the firearm suicide rate was 5.93 per 100,000 people; in 2022, it was 5.24; and in 2023, it was 5.35. Prior to 2021, the record-high rate was 6.36 per 100,000 people in 1994. Many factors can elevate the risk of suicide, and we must take action to address the root causes. But one thing remains clear: Reducing access to firearms can significantly reduce the risk of firearm suicide.

Suicide is the second leading cause of death among young people.

For the first time in nearly 20 years, suicides with a gun surpassed those by all other means in 2020.

Access to a Firearm Matters

Addressing the role of firearms is essential in suicide prevention. Most people who attempt suicide do not die—unless they use a gun. Four percent of suicide attempts that do not involve a firearm result in death. This means second chances and an opportunity for intervention. But when someone has access to a gun, it almost always turns a suicide attempt lethal: Approximately 90 percent of gun suicide attempts end in death.6Andrew Conner, Deborah Azrael, and Matthew Miller, “Suicide Case-Fatality Rates in the United States, 2007 to 2014: A Nationwide Population-Based Study,” Annals of Internal Medicine 171, no. 12 (2019): 885–95, https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/abs/10.7326/M19-1324. Given that guns are used in more than half of youth suicides—and firearm suicides make up over one-third of all youth gun deaths7Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death. Based on five-year average: 2019–2023. Ages 10–24.—removing access to firearms is one of the quickest and most effective interventions to reduce risk.

90%

90 percent of suicide attempts with a gun are fatal, while 4 percent of those not involving a gun are fatal.

Andrew Conner, Deborah Azrael, and Matthew Miller, “Suicide Case-Fatality Rates in the United States, 2007 to 2014: A Nationwide Population-Based Study,” Annals of Internal Medicine 171, no. 12 (2019): 885–95.

Each year, over 3,400 young people in the United States die by firearm suicide—an average of nine every day.8Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death. Based on five-year average: 2019–2023. Ages 10–24. The problem has gotten worse. From 2019 to 2023, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported a 14 percent increase in the youth firearm suicide rate, even as overall suicide rates for young people fell.9Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death. Based on percentage change in rates: 2019 vs. 2023. Ages 10–24. The firearm suicide rate was 4.68 per 100,000 people in 2019 and 5.35 in 2023, a 14 percent increase. The overall suicide rate was 10.22 per 100,000 people in 2019 and 9.91 in 2023, a 3 percent decrease. Even more, longer-term trends show the rate of firearm suicide among people ages 10 to 24 has increased significantly (41 percent) in the past decade—more than most other age groups.10Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death. Based on percentage change in crude rates: 2014 vs. 2023. Ages 10–24. The age group of 25–34 experienced a higher increase, at 43 percent, in comparison to the age group of 10–24 at 41 percent.

3,400

More than 3,400 young people die by firearm suicide each year.

Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death, Five-Year Average: 2019–2023. Ages 10–24.

Young people have one of the fastest-growing rates of firearm suicide of any age group in the past decade.

Rate percentage change: 2014 vs. 2023.

A National View of Youth Firearm Suicide

The rise in firearm suicide for young people did not occur uniformally across all states. The five states with the highest rates of youth suicides were Alaska, Wyoming, Montana, New Mexico, and Idaho.11Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death. Based on five-year crude rate averages: 2019–2023. Ages 10–24. And the five states with the fastest-growing rates over the past five years were North Carolina (+61 percent), Kentucky (+60 percent), Georgia (+40 percent), Tennessee (+38 percent), and Michigan (+37 percent).12Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death. Based on percentage change in crude rates: 2019 vs. 2023. Ages 10–24.

Most of these states have one thing in common: They do not have a secure storage or child-access prevention law, with the exception of North Carolina which holds gun owners accountable only if a child gains access to an unsecured gun.13New Mexico adopted the policy to hold gun owners accountable only if a child does access an unsecured gun in 2023. As a result, this law would not have impacted the rate of youth firearm suicide. Everytown’s research shows that secure storage laws have great promise for decreasing gun suicide among young people: From 1999 to 2022, the youth suicide rate for young people ages 10–24 increased by 36 percent in states with no or only reckless access storage laws, but in states with the most protective laws, the youth gun suicide rate decreased by 1 percent during this period.

When looking at urbanicity, the youth firearm suicide rate for young people is nearly two and a half times higher in the most rural areas than in urban areas,14Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death. Based on five-year crude rates: 2019–2023. Ages 10–24. Everytown defined AIAN as non-Latinx origin. The “most urban” category includes “Large Central Metro” counties and the “most rural” category includes “NonCore (Nonmetro)” counties. Connecticut is excluded due to CDC data limitations. likely due to higher household gun ownership,15Anita Knopov et al., “Household Gun Ownership and Youth Suicide Rates at the State Level, 2005–2015,” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 56, no. 3 (2019): 335–42, http://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2018.10.027. social isolation,16 Jameson K. Hirsch and Kelly C. Cukrowicz, “Suicide in Rural Areas: An Updated Review of the Literature,” Journal of Rural Mental Health 38, no. 2 (2014): 65–78, https://doi.org/10.1037/rmh0000018. the impact of the opioid epidemic,17Nora Volkow, “Suicide Deaths Are a Major Component of the Opioid Crisis That Must Be Addressed,” National Institute on Drug Abuse (blog), September 19, 2019, https://bit.ly/3jm9NgW. and limited access to mental and behavioral health services.18Kurt D. Michael and Ujjwal Ramtekkar, “Overcoming Barriers to Effective Suicide Prevention in Rural Communities,” in Youth Suicide Prevention and Intervention: Best Practices and Policy Implications, ed. John P. Ackerman and Lisa M. Horowitz (Springer, 2022), 153–59, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-06127-1_17. Poverty and income19Alison L. Cammack et al., “Vital Signs: Suicide Rates and Selected County-Level Factors—United States, 2022,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 73, no. 37 (September 2024): 810–18, http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7337e1. also have an impact on suicide: Counties with the highest poverty levels had higher youth gun suicide rates compared to those with the lowest concentrations of poverty.20 Jefferson T. Barrett et al., “Association of County-Level Poverty and Inequities with Firearm-Related Mortality in US Youth,” JAMA Pediatrics 176, no. 2 (2022): e214822, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.4822.

Rates of Firearm Suicide among Young People by State (ages 10–24)

Last updated: 8.19.2025

The Burden of Youth Firearm Suicide Is Not Felt Equally

Youth Firearm Suicide and Gender

The devastating toll of firearm suicide is affecting communities all across the United States, but some groups are suffering more than others. Looking at gender, we find that boys and young men are overwhelmingly impacted, representing nearly nine out of 10 firearm suicide victims.21Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death. Based on five-year average: 2019–2023. Ages 10–24, by gender. Young people are telling us that they are in crisis. In a 2023 CDC survey, nearly 30 percent of male high school students and more than half of female students reported persistent feelings of sadness and hopelessness during the past year.22Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report: 2013–2023,” US Department of Health and Human Services, 2024, https://www.cdc.gov/yrbs/dstr/index.html.

Boys and young men represent nearly nine out of 10 firearm suicide victims.

LGBTQ+ youth placed at a higher risk than other peers of contemplating and attempting suicide.23Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report: 2013–2023”; Asha Z. Ivey-Stephenson et al., “Suicidal Ideation and Behaviors among High School Students: Youth Risk Behavior Survey, United States, 2019,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Supplement 69, no. 1 (August 21, 2020), 47–55, http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su6901a6; Michelle M. Johns et al., “Transgender Identity and Experiences of Violence Victimization, Substance Use, Suicide Risk, and Sexual Risk Behaviors among High School Students—19 States and Large Urban School Districts, 2017,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 68, no. 3 (January 25, 2019): 67–71, https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6803a3; Jones et al., “Mental Health, Suicidality, and Connectedness.” According to the Trevor Project’s 2024 US National Survey on the Mental Health of LGBTQ Young People, 39 percent of LGBTQ people ages 13 to 24 seriously considered attempting suicide in the past year—and young people who are transgender, nonbinary, and/or people of color reported even higher rates.24The Trevor Project, “2024 U.S. National Survey on the Mental Health of LGBTQ Young People,” 2024, https://www.thetrevorproject.org/survey-2024/. Another study found that among high schoolers, LGBTQ+ youth report being three times more likely to make a suicide plan and attempt suicide than their cisgender and heterosexual peers.25Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report: 2013–2023,” 62. Homophobia, transphobia, discriminatory anti-LGBTQ+ policies, social stigma, family rejection, interpartner violence, bullying, harassment, and barriers to accessing health and safety services are all risk factors for LGBTQ+ youth suicide.26Jun Sung Hong, Dorothy L. Espelage, and Michael J. Kral, “Understanding Suicide among Sexual Minority Youth in America: An Ecological Systems Analysis,” Journal of Adolescence 34, no. 5 (2011): 885–94, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.01.002; Laura Kann et al., “Sexual Identity, Sex of Sexual Contacts, and Health-Related Behaviors among Students in Grades 9–12—United States and Selected Sites, 2015,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Surveillance Summaries 65, no. 9 (August 12, 2016): 1–202, https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.ss6509a1; The Trevor Project, “Suicide Risk Factors for LGBTQ+ Youth,” July 16, 2021, https://bit.ly/325IIaQ; Joanna Almeida et al., “Emotional Distress among LGBT Youth: The Influence of Perceived Discrimination Based on Sexual Orientation,” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 38, no. 7 (2009): 1001–14, https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9397-9; Sandy E. James et al., “The Report of the 2015 US Transgender Survey,” National Center for Transgender Equality, 2016, https://transequality.org/sites/default/files/docs/usts/USTS-Full-Report-Dec17.pdf. Receiving care that respects gender identity,27Amy E. Green, “Association of Gender-Affirming Hormone Therapy with Depression, Thoughts of Suicide, and Attempted Suicide among Transgender and Nonbinary Youth,” Journal of Adolescent Health 70, no. 4 (2022): 643–49, https://www.jahonline.org/article/S1054-139X(21)00568-1/fulltext; Giuliana Grossi, “Suicide Risk Reduces 73% in Transgender, Nonbinary Youths with Gender-Affirming Care,” HCP Live, March 8, 2022, https://www.hcplive.com/view/suicide-risk-reduces-73-transgender-nonbinary-youths-gender-affirming-care. having support from family and beyond, and fostering safe and connected environments free from discrimination can reduce the risk of suicide among LGBTQ+ youth.28Hong et al., “Understanding Suicide among Sexual Minority Youth”; Kann et al., “Sexual Identity, Sex of Sexual Contacts, and Health-Related Behaviors.”

Youth Firearm Suicide, Race, and Ethnicity

Firearm suicide rates among young people in all racial and ethnic groups have increased over the past decade.29 Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death. Percent change in crude rates: 2014 vs. 2023. Ages 10–24. Young American Indians and Alaska Natives (AIANs) have the highest firearm suicide rate, followed by white and Black youth.30Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death. Based on five-year crude rates: 2019–2023. Ages 10–24. Everytown defined AIAN, ANHPI, Black, and white as non-Latinx origin. Latinx is defined as people of Latinx origin of all races. Black youth have experienced the greatest increase in firearm suicide rates over the past 10 years—159 percent—followed by Latinx and Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (ANHPI) young people, who experienced increases of 111 and 84 percent, respectively.31Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death. Percent change in crude rates: 2014 vs. 2023. Ages 10–24. Everytown defined Black and Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander as non-Latinx origin. Latinx is defined as people of Latinx origin of all races. In 2022, for the first time since data became available in 1968, Black youth were more likely to die from gun suicide than white youth.32Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death. Crude rates: 1968–2023. Ages 10–24. Everytown defined Black and white as non-Latinx origin. Although Black youth suicide declined in 2023, it remains higher than white youth suicide.

American Indian and Alaska Native youth have the highest rate of firearm suicide.

The gun suicide rate among Black youth recently surpassed the rate among white youth.

2019 to 2023. Ages 10–24. Everytown defined Black and white as non-Latinx origin.

Learn more about suicide among:

-

American Indian and Alaska Native Youth

American Indians and Alaska Natives (AIANs) have historically had some of the highest rates of suicide in the United States, with younger AIAN people most heavily impacted.1Rachel A. Leavitt et al., “Suicides among American Indian / Alaska Natives: National Violent Death Reporting System, 18 States, 2003–2014,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 67, no. 8 (2018): 237–42, http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6708a1 And this may even be an undercount due to the issue of racial misclassification among medical examiners.2Elizabeth Arias et al., “The Validity of Race and Hispanic Origin Reporting on Death Certificates in the United States,” Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Vital and Health Statistics 2, no. 148 (2008): https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/series/sr_02/sr02_148.pdf. Youth suicide risk factors for this community include substance misuse, exposure to violence, poverty, unemployment, intergenerational trauma, and mental health disorders.3US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “To Live to See the Great Day That Dawns: Preventing Suicide by American Indian and Alaska Native Youth and Young Adults,” April 2010, https://library.samhsa.gov/product/to-live-to-see-the-great-day-that-dawns-preventing-suicide-american-indian-alaska-native-youth/sma10-4480; US Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Minority Health, “Mental and Behavioral Health—American Indians / Alaska Natives,” May 19, 2021, https://minorityhealth.hhs.gov/omh/browse.aspx?lvl=4&lvlid=39; André B. Rosay, “Violence against American Indian and Alaska Native Women and Men,” June 1, 2016, https://bit.ly/3shGVxE. Any of these factors can lead to feelings of despair: In 2023, nearly half of AIAN high school students reported persistent feelings of sadness or hopelessness, and one in four considered attempting suicide in the past year.4Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report: 2013–2023,” 58, 60. To address this, in partnership with tribal communities, government agencies and other organizations should develop culturally relevant suicide prevention programs and medical and mental health services, including known protective factors such as belonging to one’s culture and a strong tribal/spiritual bond.5US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, “To Live to See the Great Day That Dawns,”, 8, https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/sma10-4480.pdf.

Learn more about suicide prevention in AIAN communities through the Center for Native American Youth and the US Department of Health and Human Services’ Indian Health Service—and learn more about suicide prevention in rural areas through the Suicide Prevention Resource Center and the CDC.

-

White Youth

Overall, white people in the United States experience the highest rate of firearm suicide.1Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death. Based on five-year age-adjusted rate: 2019–2023. All ages. Everytown defined white as non-Latinx origin. Among young people, on average, white youth have the second-highest rate of firearm suicide2Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death. Based on five-year crude rates: 2019–2023. Ages 10–24. Everytown defined white as non-Latinx origin. but constitute the majority (62 percent) of young people who die by firearm suicide.3Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death. Based on five-year average: 2019–2023. Ages 10–24. Everytown defined white as non-Latinx origin. In 2023, nearly one in three white high school students reported that they had poor mental health in the past 30 days—the second-highest rate of any racial and ethnic group—and more than one in five said they had considered attempting suicide.4Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report: 2013–2023,” 58, 60. High rates of gun ownership among white people5Kim Parker et al., “America’s Complex Relationship with Guns,” Pew Research Center, 2017, 16–28, https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/20/2017/06/Guns-Report-FOR-WEBSITE-PDF-6-21.pdf. suggest that counseling about lethal means6Counseling on Access to Lethal Means (CALM) is one example of a program that trains medical professionals to perform this practice. See Counseling on Access to Lethal Means (CALM), Suicide Prevention Resource Center, accessed June 2, 2025, https://bit.ly/4dPo1EI. and limiting access to firearms through secure storage are key components to suicide prevention efforts for these communities. Learn more about suicide prevention through the Suicide Prevention Resource Center and the CDC.

-

Black Youth

Black youth use guns more often in suicide than any other racial group: 58 percent of suicide deaths among Black youth involve a firearm.1Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death. Crude rates: 2019–2023. Ages 10–24. Everytown defined Black as non-Latinx origin. Studies on Black teens have shown that risk factors for suicide include depression; traumatic experiences such as exposure to racism, discrimination, and neighborhood violence; and poor support from family.2Congressional Black Caucus, Emergency Taskforce on Black Youth Suicide and Mental Health, “Ring the Alarm: The Crisis of Black Youth Suicide in America,” 2019, 14–15, https://watsoncoleman.house.gov/imo/media/doc/full_taskforce_report.pdf. Yet young Black people are less likely than their white peers to have had a mental health diagnosis prior to suicide.3Sofia Chaudhary et al. “Youth Suicide and Preceding Mental Health Diagnosis,” JAMA Network Open 7, no. 7 (2024): https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.23996; US Department of Health and Human Services, “African American Youth Suicide: Report to Congress,” 2020, https://bit.ly/3KogeNv.

In addition, mass incarceration and the school-to-prison pipeline adversely impact Black youth in many ways. Black children are two times more likely than their white peers to have an incarcerated member of their household, which robs children of their families and communities.4Connor Maxwell and Danyelle Solomon, “Mass Incarceration, Stress, and Black Infant Mortality: A Case Study in Structural Racism,” Center for American Progress, 2018, https://www.americanprogress.org/article/mass-incarceration-stress-black-infant-mortality/. Black students often experience cultural policing through disciplinary sanctions and hypersurveillance from school resource officers and law enforcement for the way they dress and express themselves.5Odis Johnson Jr., Jason Jabbari, and Olivia Marcucci, “Disparate Impacts: Balancing the Need for Safe Schools with Racial Equity in Discipline,” Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences 6, no. 2 (2019): 162–69, https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732219864707. As a result, they are also arrested more often than students of other racial and ethnic groups.6US Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, “Student Discipline and School Climate in US Public Schools,” 2020–2021 Civil Rights Data Collection, November 2023, https://www.ed.gov/sites/ed/files/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/crdc-discipline-school-climate-report.pdf; US Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights, “Data Highlights on School Climate and Safety in Our Nation’s Public Schools,” 2015–2016 Civil Rights Data Collection: School Climate and Safety, 2018, https://bit.ly/3aVDJgx; Amir Whitaker et al., “Cops and No Counselors: How the Lack of School Mental Health Staff Is Harming Students,” American Civil Liberties Union, 2019, https://bit.ly/3xzz0fF. Removing children from their families, schools, and communities increases the risk of poverty and has been associated with post-traumatic stress disorder, poor school performance, and feelings of alienation.7Saneta deVuono-powell et al., “Who Pays? The True Cost of Incarceration on Families,” Ella Baker Center for Human Rights, 2015, https://ellabakercenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Who-Pays-FINAL.pdf; Kelly Welch et al., “Cumulative Racial and Ethnic Disparities along the School-to-Prison Pipeline,” Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency 59, no. 5 (2022): 574–626, https://doi.org/10.1177/00224278211070501. Important steps to prevent suicide include centering the voices of Black youth in prevention efforts, developing safe and supportive spaces, improving access to mental health care, and investing in Black mental health professionals and researchers.8Janel Cubbage and Leslie Adams, “Still Ringing the Alarm: An Enduring Call to Action for Black Youth Suicide Prevention,” Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Department of Mental Health, 2023, https://publichealth.jhu.edu/sites/default/files/2023-08/2023-august-still-ringing-alarm.pdf.

Learn more about how to address suicide among Black youth from the Congressional Black Caucus Emergency Taskforce’s report on Black Youth Suicide and Mental Health and through the Mental Health Coalition./

-

Latinx Youth

Over 500 young Latinx people die each year by firearm suicide.1Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death. Based on five-year average: 2019–2023. Ages 10–24. Latinx is defined as people of Latinx origin of all races. As a group, Latinx youth have seen the second-greatest increase in firearm suicide rate over the past decade.2Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death. Based on percentage change in crude rates: 2014 vs. 2023. Ages 10–24. Latinx is defined as people of Latinx origin of all races. Various factors—including intimate partner conflicts, family problems, abuse, poverty, stress surrounding immigration, and food insecurity—can influence Latinx youth suicide attempts.3Christina Seowoo Lee and Y. Joel Wong, “Racial/Ethnic and Gender Differences in Antecedents,” Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology 26, no. 4 (2020): 532–43, https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000326; Carolina Hausmann-Stabile and Lauren E. Gulbas, “Latina Adolescent Suicide Attempts: A Review of Familia, Cultural and Community Protective and Risk Factors,” in Handbook of Youth Suicide Prevention: Integrating Research into Practice, ed. Regina Miranda and Elizabeth L. Jeglic (Springer, 2021), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-82465-5_16; Meryn Hall et al., “Suicide Risk and Resiliency Factors among Hispanic Teens in New Mexico: Schools Can Make a Difference,” Journal of School Health 88, no. 3 (2018): 227–36, https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12599; Caroline Silva and Kimberly A. Van Orden, “Suicide among Hispanics in the United States,” Current Opinion in Psychology 22 (2018): 44–49, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.07.013; The Trevor Project, “The Trevor Project Research Brief: Latinx LGBTQ Youth Suicide Risk,” 2020, https://bit.ly/3s0OacR; The Trevor Project, “The Mental Health and Well-Being of Latinx LGBTQ Young People,” 2023, https://www.thetrevorproject.org/research-briefs/the-mental-health-and-well-being-of-latinx-lgbtq-young-people/. In 2023, nearly one in five Latinx high school students reported that they seriously contemplated suicide in the past year.4Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report: 2013–2023,” 60. Among Latinx high school students, 18 percent reported seriously considering attempting suicide in the past year. Young Latinx people also have low mental health service utilization due to stigma, poor mental health literacy, unfavorable attitudes toward seeking help, costs, language barriers, and concerns about legal status.5Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, “2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Hispanics, Latino or Spanish Origin or Descent,” 2022, https://www.samhsa.gov/data/report/2020-nsduh-hispanics-latino-or-spanish-origin; Leopoldo J. Cabassa, Luis H. Zayas, and Marissa C. Hansen, “Latino Adults’ Access to Mental Health Care: A Review of Epidemiological Studies,” Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 33, no. 3 (2006): 316–30, https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10488-006-0040-8; Susan De Luca, Karen Schmeelk-Cone, and Peter Wyman, “Latino and Latina Adolescents’ Help-Seeking Behaviors and Attitudes regarding Suicide Compared to Peers with Recent Suicidal Ideation,” Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 45, no. 5 (2015): 577–87, https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12152; Mudita Rastogi, Nicole Massey-Hastings, and Elizabeth Wieling, “Barriers to Seeking Mental Health Services in the Latino/a Community: A Qualitative Analysis,” Journal of Systemic Therapies 31, no. 4 (2012): 1–17, https://doi.org/10.1521/jsyt.2012.31.4.1; National Alliance on Mental Illness, “Hispanic/Latinx,” accessed October 9, 2024, https://bit.ly/3kyaG8P. Latinx communities need better access to quality trauma-informed mental health resources that are culturally affirmative and linguistically accessible.6Silva and Van Orden, “Suicide among Hispanics;” Cabassa et al., “Latino Adults’ Access to Mental Health Care.” Positive relationships with educators and other adults at school enable young Latinx students to feel more comfortable when speaking out about suicidal ideation, underscoring the importance of fostering a positive, supportive school environment.7Hall et al., “Suicide Risk and Resiliency Factors.”

Learn more about suicide prevention in Latinx communities from the Suicide Prevention Resource Center.

-

Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Youth

Although young Asian, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander (ANHPI) people die by firearm suicide at a lower rate than other racial and ethnic groups, that rate has nearly doubled over the past decade.1Everytown Research analysis of CDC, WONDER, Underlying Cause of Death. Based on percentage change in crude rates: 2014 vs. 2023. Ages 10–24. Everytown defined ANHPI as non-Latinx origin. Many factors can elevate this risk, such as discrimination, ethnic marginalization, and acculturation,2Laura C. Wyatt et al., “Risk Factors of Suicide and Depression among Asian American, Native Hawaiian, and Pacific Islander Youth: A Systematic Literature Review,” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 26, no. 2 (2015): 191–237, https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2015.0059. as well as stress from family conflicts and school pressures.3Anna S. Lau et al., “Correlates of Suicidal Behaviors among Asian American Outpatient Youths,” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 8, no. 3 (2002): 199–213, http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1099-9809.8.3.199; Lee and Wong, “Racial/Ethnic and Gender Differences in Antecedents”; Y. Joel Wong, Chris Brownson, and Alison E. Schwing, “Risk and Protective Factors Associated with Asian American Students’ Suicidal Ideation: A Multicampus, National Study,” Journal of College Student Development 52, no. 4 (2011): 396–408, https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/1/article/446117/pdf. Importantly, the ANHPI community is also incredibly diverse, comprising a wide range of cultural and linguistic subgroups. For example, a study on ANHPI youth suicide rates shows a wide variation among subgroups, and found that “Other Asian,” Chinese, and Asian Indians had the highest number of suicides from 2018 to 2021.4Miles P. Reyes, Ivy Song, and Apurva Bhatt, “Breaking the Silence: An Epidemiological Report on Asian American and Pacific Islander Youth Mental Health and Suicide (1999–2021),” Child and Adolescent Mental Health 29, no. 2 (2024): 136-44, https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12708. This underscores the need for further research and targeted, culturally competent solutions and prevention efforts that are linguistically accessible.5Y. Joel Wong et al., “Asian Americans’ Proportion of Life in the United States and Suicide Ideation: The Moderating Effects of Ethnic Subgroups,” Asian American Journal of Psychology 5, no. 3 (2014): 237–42, https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033283; Lillian Polanco-Roman et al., “Emotion Expressivity, Suicidal Ideation, and Explanatory Factors: Differences by Asian American Subgroups Compared to White Emerging Adults,” Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology 30, no. 1 (2019): 11–21, https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000313.

Learn more about suicide prevention in the ANHPI community from the Suicide Prevention Resource Center.

What Is Contributing to This Decade-Long Rise?

Online and School Environments

The rise in firearm suicide rates among young people is clear, and researchers are theorizing what could be behind the trend. One important factor is that for the past decade, the lives of young people have been reoriented to emphasize the use of technology such as social and digital media. Although some researchers have noted upsides in connectedness, many have linked today’s technology to increasing depression, anxiety, loneliness, and even self-harm.33Jean M. Twenge, “Increases in Depression, Self-Harm, and Suicide among U.S. Adolescents after 2012 and Links to Technology Use: Possible Mechanisms,” Psychiatric Research & Clinical Practice 2, no. 1 (2020): https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.prcp.20190015. The increasing use of technology has also made devastating cyberbullying possible.34Raquel António, Rita Guerra, and Carla Moleiro, “Cyberbullying during COVID-19 Lockdowns: Prevalence, Predictors, and Outcomes for Youth,” Current Psychology 43 (2023): 1067–83, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04394-7. A survey of young people ages 12 to 17 found that students who experienced either school-based or online bullying were more likely to report suicidal thoughts, and students who experienced both forms of bullying were more likely to report suicide attempts compared to their peers who did not experience bullying.35Sameer Hinduja and Justin W. Patchin, “Connecting Adolescent Suicide to the Severity of Bullying and Cyberbullying,” Journal of School Violence 18, no. 3 (2019): 333–46, https://doi.org/10.1080/15388220.2018.1492417. Bullying, whether in person or online, amplifies the risk of suicidal behavior among adolescents.

In the face of these multiple challenges, students are also returning to school to news of mass shootings across the country. Research has found that adolescents who are concerned about shootings or other violence at their school—or other schools—experience heightened symptoms of panic and anxiety.36Kira E. Riehm et al. “Adolescents’ Concerns about School Violence or Shootings and Association with Depressive, Anxiety, and Panic Symptoms,” JAMA Network Open 4, no. 11 (2021): e2132131, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.32131. This all also comes at a time when students are asked to learn in environments that have unannounced fear-provoking active-shooter drills, which have been found to increase depression, stress, anxiety, and physiological health problems among students.37Mai ElSherief et al., “Impacts of School Shooter Drills on the Psychological Well-Being of American K–12 School Communities: A Social Media Study,” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 8, no. 315 (2021): https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-021-00993-6.

Continued Impacts of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic reshaped the lives of teens and young adults well beyond the direct effects of the illness itself. The disruption of school closures was compounded by stressors exacerbated during the pandemic such as economic and health challenges, the illness and death of loved ones, social isolation, and mental stress—and youth continue to experience these ripple effects.38Jones et al., “Mental Health, Suicidality, and Connectedness;” Stirling T. Argabright et al., “COVID-19-Related Financial Strain and Adolescent Mental Health,” The Lancet Regional Health–Americas 16 (2022): 1–10; Susan D. Hillis et al., “COVID-19-Associated Orphanhood and Caregiver Death in the United States,” Pediatrics 148, no. 6 (2021): https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2021-053760. These consequences can be seen through the rise of suicidal behavior among young people during the pandemic and since then.

During periods of the first year of the pandemic, there was a disturbing rise in emergency department visits for suspected suicide attempts among young people ages 12 to 25.39Ellen Yard et al., “Emergency Department Visits for Suspected Suicide Attempts among Persons Aged 12–25 Years before and during the COVID-19 Pandemic—United States, January 2019–May 2021,” Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report 70, no. 24 (2021): 888–94, https://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7024e1. Tragically, these rates continued to increase during the second year of the pandemic.40Alexandra Junewicz et al., “The Persistent Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Pediatric Emergency Department Visits for Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors,” Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior 54, no. 1 (2024): 38–48, https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.13016. The CDC’s Youth Risk Behavior Survey, conducted in 2023, found that one in five high school students seriously considered attempting suicide and nearly one in 10 had attempted suicide in the past year.41Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, “Youth Risk Behavior Survey Data Summary & Trends Report: 2013–2023,” 60, 64.

The pandemic also has a lasting impact on children who are coping with prolonged symptoms of COVID-19, which include headaches, trouble with memory, stomach pain, and trouble sleeping,42Rachel S. Gross et al. “Characterizing Long COVID in Children and Adolescents,” JAMA 332, no. 14 (2024): 1174–88, http://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2024.12747 . as well as the burden of stepping into the caretaking roles of family members with disabilities related to long COVID.43Emma Armstrong-Carter et al. “The United States Should Recognize and Support Caregiving Youth,” Social Policy Report 34, no. 2 (2021): 1–24, https://doi.org/10.1002/sop2.14. These additional stressors lead to daily pressures, mental and physical health problems, and limited educational and employment opportunities for young people during their transition to adulthood—which can lead to feelings of hopelessness.44Emma Armstrong-Carter, Elizabeth Olson, and Eva Telzer, “A Unifying Approach for Investigating and Understanding Youth’s Help and Care for the Family,” Child Development Perspectives 13, no. 3 (2019): 186–92, https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12336. Young people also continue to navigate the traumatic impacts of experiencing physical and emotional abuse from family members during the pandemic45Kathleen H. Krause et al., “Disruptions to School and Home Life among High School Students during the COVID-19 Pandemic—Adolescent Behaviors and Experiences Survey, United States, January–June 2021,” MMWR Supplements 71, no. 3 (2022): 28–34, https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.su7103a5.—one of the most commonly identified circumstances precipitating suicide among youth ages 10 to 24 in the United States today.46Chaudhary et al., “Youth Suicide and Preceding Mental Health Diagnosis.”

A Surge in Gun Sales

Driven by fear and anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic, people in the United States bought a record number of guns in 2020—an estimated 22 million guns, a 64 percent increase over 2019.47Daniel Nass and Champe Barton, “How Many Guns Did Americans Buy Last Month? We’re Tracking the Sales Boom,” The Trace, May 13, 2025, https://www.thetrace.org/2020/08/gun-sales-estimates/. Percent change in estimated gun sales 2019 vs. 2020. Gun sales have declined since, but remain higher than prepandemic sales: an estimated 88 million guns were sold from 2020 to 2024, compared to 71 million from 2015 to 2019—a 24 percent increase.48Nass and Barton, “How Many Guns Did Americans Buy Last Month?” Roughly 30 million children in the United States now live in homes with firearms—up 7 million since 2015. Researchers estimate that a staggering 4.6 million of these children live in households with at least one loaded and unlocked firearm.49Matthew Miller and Deborah Azrael, “Firearm Storage in US Households with Children: Findings from the 2021 National Firearm Survey,” JAMA Network Open 5, no. 2 (2022): https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.48823.

88M

An estimated 88 million guns were sold in the United States from 2020 to 2024—a 24 percent increase compared to the previous five years.

Source: Daniel Nass and Champe Barton, “How Many Guns Did Americans Buy Last Month? We’re Tracking the Sales Boom,” The Trace, April 24, 2025, https://www.thetrace.org/2020/08/gun-sales-estimates/. Percent change in estimated gun sales 2020–2024 vs. 2015–2019.

The ready access to guns is deeply concerning, given that seven in 10 firearm suicides by young people take place in or around a home,50Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS), 2020–2022. Ages 10–24. On average, 70 percent of firearm suicides among young people ages 10–24 take place in a house or an apartment, including the driveway, porch, or yard. and 79 percent of firearm suicides by children (ages 17 or younger) and 44 percent of young adults (ages 18 to 20) involve a gun belonging to a family member.51Catherine Barber et al., “Who Owned the Gun in Firearm Suicides of Men, Women, and Youth in Five US States?” Preventive Medicine 164 (2022): 107066, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107066. A recent study found that the gun used in suicides of Black and Latinx youth (10 to 18 years old) were more likely to be kept loaded and unlocked than among adolescents as a whole.52Eugenio Weigend Vargas et al., “Adolescent Firearm Suicides in the United States: Exploring Racial and Ethnic Differences, 2004 to 2020,” Youth & Society 56, no. 8 (2024): 1542–57, https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X241277202. Parents may believe that their guns are kept out of sight or that their children have never handled their firearms. But the evidence tells us otherwise. One study found that even though 70 percent of parents think their teen cannot access the gun(s) in their home, half of teens said they could gain access to a loaded gun in their home in under an hour, including one-third who said they could do so in under five minutes.53Carmel Salhi, Deborah Azrael, and Matthew Miller, “Parent and Adolescent Reports of Adolescent Access to Household Firearms in the United States,” JAMA Network Open 4, no. 3 (2021): e210989, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0989.

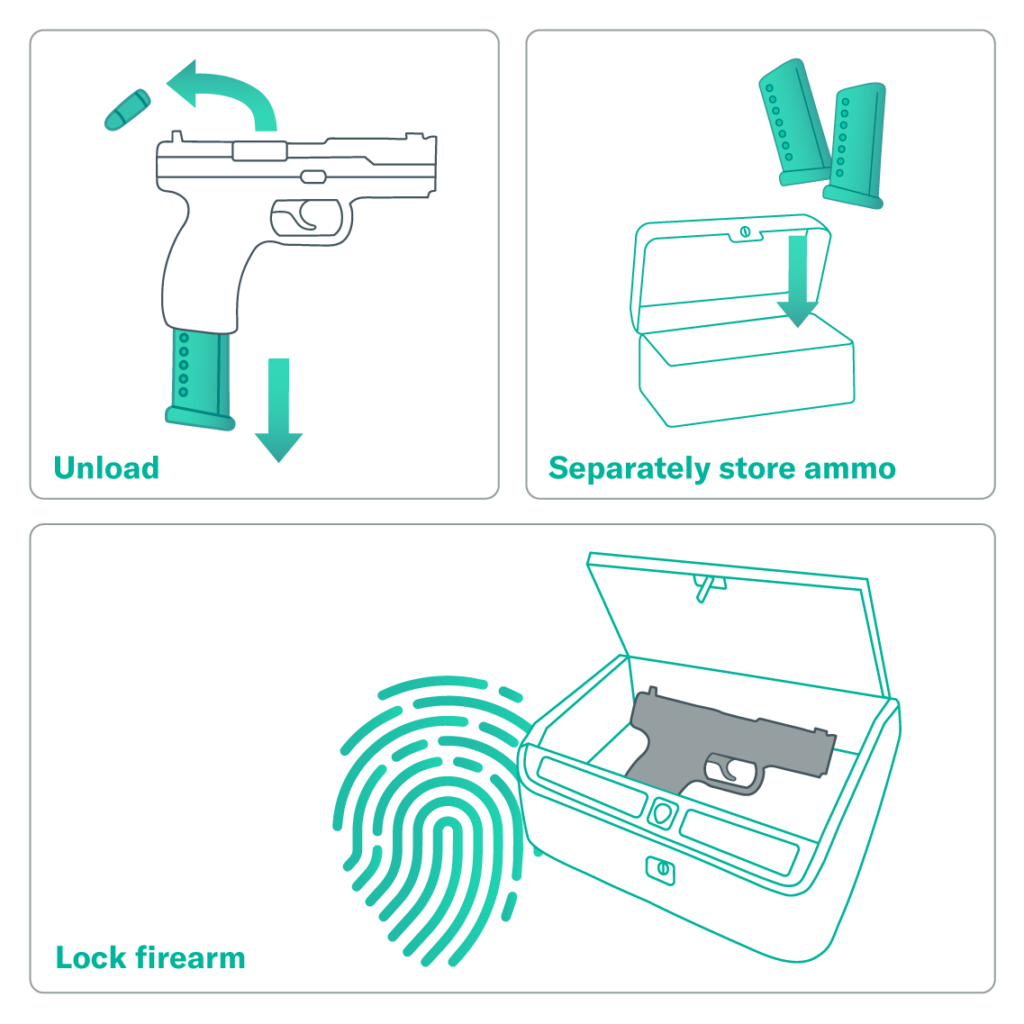

What Is Secure Firearm Storage?

Gun owners can reduce the risk of youth suicide—and gun violence in general—by securing all guns in the home. That means storing them unloaded, locked, and separate from ammunition. Gun owners and others can also reduce risks by asking about secure gun storage in all homes their children visit. These simple actions can save a child’s life.

Learn more about the Be SMART campaign to raise awareness about how secure gun storage can save lives.

Recommendations for Action

Thousands of young lives are tragically cut short every year by suicide. We can take actions to mitigate the risk of suicide and potentially save lives. Effective suicide prevention among young people in the United States requires a multifaceted approach. Recommendations include the following:

Enact legislation and policies to limit easy and immediate access to firearms.

Mechanisms that create time and space between access to lethal means and someone experiencing crisis are proven to reduce the risk of suicide. The vast majority of people who survive a suicide attempt do not go on to die by suicide.54David Owens, Judith Horrocks, and Allan House, “Fatal and Non-fatal Repetition of Self-Harm: Systematic Review,” British Journal of Psychiatry 181, no. 3 (2002): 193–99, https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.181.3.193. The following practices and policies limit easy and immediate access to firearms and are proven to reduce firearm suicide rates.

- Secure storage laws prevent unauthorized access by children and teens by requiring gun owners to lock up their firearms.

- Extreme risk laws, sometimes referred to as “red flag” laws, allow loved ones or law enforcement to intervene by petitioning a court for an order to temporarily prevent someone in crisis from accessing guns.

- Waiting-period laws require a certain number of days to pass between the purchase of a gun and when the buyer can take possession of that gun. This creates a time buffer for someone who is in crisis having access to a gun.

- Permit-to-purchase laws, in addition to background checks, ensure that a person attempting to buy a gun is not legally prohibited from having a gun and is not too young to buy one.

Develop and scale preventive programs and tools.

Communities, cities, and states can develop or implement a wide array of programs that put time and space between a young person in crisis and firearms. Many of these interventions emphasize voluntary actions by friends, family, or trusted community members rather than interaction with courts or law enforcement. Everytown’s Continuum of Gun Access Interventions for Preventing Gun Suicide summarizes many of these options.

- Secure storage awareness programs: Gun owners can make their homes and communities safer by storing their guns securely in their homes and vehicles. This means storing firearms unloaded, locked, and separate from ammunition. Even when a state does not have an underlying secure storage law, awareness-raising campaigns, like Be SMART, can encourage voluntary behavior change by helping ensure that firearm owners are aware of the risks of youth suicide and best practices for storing their guns. School districts can take action by passing resolutions requiring schools to provide parents with resources about secure gun storage.55Students Demand Action, “Urge Your School Board to Act on School Safety,” January 26, 2022, https://studentsdemandaction.org/report/urge-your-school-board-to-act-on-school-safety/. State legislatures can enact laws mandating this requirement also.56Everytown for Gun Safety, ”Following Tireless Advocacy by California Moms Demand Action, Students Demand Action, California Legislature Passes Groundbreaking Gun Violence Prevention Bills,” press release, August 9, 2022, https://www.everytown.org/press/following-tireless-advocacy-by-california-moms-demand-action-students-demand-action-california-legislature-passes-groundbreaking-gun-violence-prevention-bills/.

- Out-of-home storage: Temporarily storing a gun securely outside of the home by transferring the firearm to another trusted person or storing it at a secure third-party location can be life-saving when someone is in crisis, including young people residing in or visiting the home.57Depending on state law, gun owners may be able to temporarily transfer a firearm(s) to another person, such as a trusted family member or friend. Many businesses and agencies may consider temporarily storing firearms, including local law enforcement agencies, veteran service organizations, firearm retailers, shooting ranges, or commercial firearms storage facilities. Firearm storage maps have been developed to help community members find third-party storage options in several localities and states, including Colorado, Maryland, Mississippi, Missouri, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, and Washington.

- Health care provider counseling on lethal means access: Physicians and other medical professionals are crucial sources of information about the risk of firearm access. By asking patients about firearm access and counseling them about firearm suicide risk, they can help prevent firearm suicide deaths. Counseling on Access to Lethal Means (CALM) is one example of a program that trains medical professionals to perform this practice.

- Public awareness and purchaser education: Access to a firearm increases the risk of suicide for all people in a household.58Andrew Anglemyer, Tara Horvath, and George Rutherford, “The Accessibility of Firearms and Risk for Suicide and Homicide Victimization among Household Members: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis,” Annals of Internal Medicine 160 (2014): 101–10, https://www.acpjournals.org/doi/10.7326/m13-1301. In many communities, gun dealers are considered trusted messengers by gun owners and can play a role in building public awareness about the suicide risk posed by firearm access and how to mitigate that risk. Through programs like the Gun Shop Project dozens of firearm retailers nationwide display information about the risks of firearm access—particularly as it pertains to suicide. Training and awareness-raising programs can empower more individuals, especially gun owners, to openly discuss risks and mitigation strategies.

Invest in research and prevention programs.

More research is needed to better understand the significant rise in youth firearm suicide and to develop targeted prevention efforts. Myriad factors influence risks for suicide, some of which are unique to specific populations. So it is critically important to have research that disaggregates data by subgroups and to develop evidence-informed and culturally appropriate interventions.59Lee and Wong, “Racial/Ethnic and Gender Differences in Antecedents”; Lau et al., “Correlates of Suicidal Behaviors”; Polanco-Roman et al., “Emotion Expressivity, Suicidal Ideation, and Explanatory Factors;” Lisa R. Fortuna et al., “Prevalence and Correlates of Lifetime Suicidal Ideation and Attempts among Latino Subgroups in the United States,” Journal of Clinical Psychology 68, no. 42 (2007): 572–81, https://dx.doi.org/10.4088/jcp.v68n0413; US Department of Health and Human Services, “African American Youth Suicide.” Failure to address the unique risk factors linked to specific demographic groups can negatively affect people in need, further exacerbate disparities, and impact program outcomes.60Sarah P. Carter et al., “Suicide Attempts among Racial and Ethnic Groups in a Nationally Representative Sample,” Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities 9 (2021): 1783–93, https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-021-01115-3.

Know the risk factors and warning signs.

Knowing the risk factors and warning signs that someone may be at risk of taking their life is critical to saving lives. Although these factors and behaviors—whether in yourself or in a loved one—do not automatically mean someone is at risk for suicide, they are important to recognize, especially if they are new or have increased. To learn more, read about the warning signs of suicide risk from the American Association of Suicidology and American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, which include:

- Threatening or talking about wanting to hurt or kill themselves.

- Looking for ways to kill themselves, such as attempting to acquire a firearm or pills.

- Increased use of alcohol and/or other drugs.

- Feeling like they have no reason to live or no sense of purpose in life.

- History or signs of depression, anxiety, agitation, and/or difficulty with sleep.

- Withdrawal from friends, family, and society.

- Reaching out to say goodbye to loved ones and/or giving away their possessions.

- A sudden and unexplainable improvement in their mood.61American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, “Risk Factors, Protective Factors, and Warning Signs,” accessed June 2, 2025, https://afsp.org/risk-factors-protective-factors-and-warning-signs/; American Association of Suicidology, “Know the Signs: How to Tell If Someone Is Suicidal,” June 2, 2025, https://afsp.org/risk-factors-protective-factors-and-warning-signs/.

SCHOOL DISTRICTS HAVE IMPLEMENTED ANONYMOUS TIP LINES THAT ARE SAVING LIVES.

Initially developed as a mechanism for students to anonymously report concerns about their classmates and prevent school shootings, students are now using school tip lines to report others who are at risk of self-harm or are feeling suicidal.1Tyler Kingkade, “School Tip Lines Were Meant to Stop Shootings, but Uncovered a Teen Suicide Crisis,” NBC News, February 1, 2020, https://nbcnews.to/3gi4kpB Statewide school safety tip lines in Oregon and Pennsylvania received 204 and 2,424 tips about suicide, respectively, during the 2023–2024 school year. This is compared to 208 tips in Oregon and 1,111 tips in Pennsylvania about threats against schools.2Number of tips for “suicidal ideation” (reported by another person and self-reported) and “threat of planned school attack,” excluding duplicate and prank tips in Oregon, and “suicide / suicide ideation” and “threat against school” in Pennsylvania. Oregon State Police, Safe Oregon, “Safe Oregon Annual Report, July 1, 2023–June 30, 2024,” 2024, https://www.safe2saypa.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/2023-2024-Annual-Report.pdf; Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Office of Attorney General, “Safe2Say Something Annual Report, 2023–2024 School Year,” 2023, https://www.safeoregon.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/SAFEOREGON-2024-Annual-Report-1.pdf. Given the unprecedented uptake of these programs, Everytown recommends that more school districts implement anonymous tip lines to address the rise in youth suicide and keep our students safe.

Schools should consider using Sandy Hook Promise’s Know the Signs campaign and Say Something program, which are now in several states. Pennsylvania has used this program to develop its Safe2Say Something tip line program, which trains students on warning signs and encourages them to report a classmate who may be at risk of harming themselves or others.3Sandy Hook Promise, “Safer Schools through Proven Prevention Programs,” accessed October 10, 2024, https://bit.ly/34L0ymx.

Learn how to talk about mental health.

If a friend, family member, or loved one is exhibiting any of the above warning signs and you are worried that they are contemplating suicide, it is important to have an open and honest conversation with them and not wait with the hope that they will start to feel better. Contrary to popular myth, talking to loved ones about suicide does not make them suicidal or plant the idea in their head.62Christine Polihronis et al., “What’s the Harm in Asking? A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis on the Risks of Asking about Suicide-Related Behaviors and Self-Harm with Quality Appraisal,” Archives of Suicide Research 26, no. 2, (2020): https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2020.1793857. In fact, you can make a difference by offering support and help. The American Foundation for Suicide Prevention RealConvo Guide urges us to let them know you are listening and taking them seriously:

- Show your support and that you care. The RealConvo Guide includes examples of phrases you can use to facilitate these conversations.

- Encourage them to keep talking—and actively listen by expressing curiosity and interest in the details.

- Ask them about changes in their life and how they are coping.

- Be direct if you suspect that they are thinking about suicide. Use the words “suicide” or “kill yourself” if you are asking about suicidal thinking.

- Follow their lead and know when to take a break.

- Find a way to bring up the benefits of professional help and provide them with resources on how to do so.

REACH OUT FOR HELP

Suicide prevention hotlines are staffed by trained counselors who assess callers for suicide risk, provide crisis counseling, and offer referrals, including lethal means counseling when someone mentions that they have firearms or other lethal means in the home. These hotlines are saving lives every day. After Congress designated a new phone number, the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline transitioned to the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline in July 2022. The Lifeline has experienced increasing demand: from January 2022 to December 2024, 988 routed more than 15 million contacts via phone, text, and chat, double the contacts during the previous three years.1Everytown Research analysis of 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline performance metrics. There were 7,253,558 Lifeline contacts from 2019 to 2021, compared to 15,040,694 from 2022 to 2024. Data excludes contacts offered to the Veterans Crisis Line. Data for 2019–2021 available at https://web.archive.org/web/20231130121443/https://988lifeline.org/by-the-numbers/; data for 2022–2024 available at https://www.samhsa.gov/mental-health/988/performance-metrics. Free and confidential support is available when you, a loved one, or a peer needs to talk to someone.

Resources

-

Free and Confidential Crisis Lines

- 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline (formerly the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline) provides free and confidential support for people in distress or suicidal crisis. Call or text 988 to talk with a counselor—or visit 988lifeline.org/chat to chat online with one. Call, text, and chat lines are available 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

- Crisis Text Line provides free live support with a trained crisis counselor. Text HOME to 741741, visit connect.crisistextline.org/chat, or message HOME to 1-443-787-7678 on WhatsApp.

- Teen Line connects teens who need someone to talk to with other trained teens who can listen and present available options. Call 1-800-852-8336 from 6 p.m. to 10 p.m. PT or text TEEN to 839863 from 6 p.m. to 9 p.m. PT.

- The Trevor Project provides crisis intervention and suicide prevention services to LGBTQ+ young people under age 25. Call 1-866-488-7386, text START to 678-678, or visit chat.trvr.org to chat with a counselor 24/7.

- Trans Lifeline Hotline provides support services by trans people, for trans and questioning callers in crisis, 24/7. Call 1-877-565-8860.

- Veterans Crisis Line provides confidential support to anyone, regardless of Veteran Affairs status. Call 988 and press 1; text 838255; or chat 24/7.

- Your Life Your Voice connects teens in need of help with crisis counselors 24/7. Call 1-800-448-3000 or text VOICE to 20121.

-

Suicide Prevention and Mental Health Organizations

- Active Minds has chapters on more than 800 college campuses that work to empower students to talk openly about their mental health so that no one struggles alone.

- Asian Mental Health Collective provides a list of culturally competent therapists for API clients and works to raise awareness about the importance of mental health care and challenging the stigma surrounding it.

- Black Mental Health Alliance aims to develop and promote culturally relevant trainings and services to support the health of Black people and other communities in the United States.

- Center for Native American Youth at the Aspen Institute works to improve the health and safety of Native youth through research, advocacy, and policy change.

- Loveland Foundation provides financial assistance to Black women and girls nationwide seeking therapy, with the goal of prioritizing opportunity, access, validation, and healing.

- National Alliance for Hispanic Health is a science-based and community-driven organization that focuses on improving the health and well-being of Hispanic people and providing quality care to all.

- American Association of Suicidology’s National Center for the Prevention of Youth Suicide works to identify youth at risk, develop strategies to move prevention upstream, and engage and empower youth to be partners in their suicide prevention efforts.

- Society for the Prevention of Teen Suicide, founded by two dads who lost teenage children to suicide, encourages public awareness about the issue through the development and promotion of educational training programs.

Acknowledgement

Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund would like to gratefully acknowledge Dr. Sofia Chaudhary, Assistant Professor in Pediatrics and Emergency Medicine at Emory University School of Medicine, and Brian Malte, Executive Director of Hope and Heal Fund, for their expert review of this report.

Learn More:

Everytown Research & Policy is a program of Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, an independent, non-partisan organization dedicated to understanding and reducing gun violence. Everytown Research & Policy works to do so by conducting methodologically rigorous research, supporting evidence-based policies, and communicating this knowledge to the American public.