Summer Youth Employment Programs for Violence Prevention

A Guide to Implementation and Costing

Executive Summary

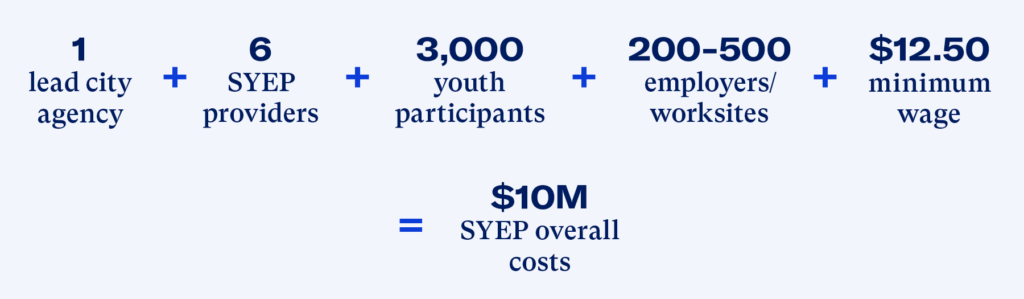

Homicide rates across the United States have increased 35 percent since before the Covid-19 pandemic. Violence also follows seasonal patterns, routinely peaking in the summer months, meaning that cities feel these effects most strongly then.1Leah H. Schinasi and Ghassan B. Hamra, “A Time Series Analysis of Associations between Daily Temperature and Crime Events in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,” Journal of Urban Health 94, no. 6 (2019): 892–900, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28687898/; Janet L. Lauritsen and Nicole White, Seasonal Patterns in Criminal Victimization Trends (Washington, DC: US Department of Justice Bureau of Justice Statistics, June 2014), https://bjs.ojp.gov/content/pub/pdf/spcvt.pdf. A growing body of evidence shows that summer youth employment programs (SYEPs) aimed at the young people most at risk for or with histories of violence are a promising intervention to reduce violent crime in cities. With this guide, Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund’s Research team (Everytown) aims to help cities and funders understand the key components and costs of implementing SYEPs. To make the process simpler, Everytown also developed a costing tool that can be tailored to specific needs and budgets. As an example, Everytown estimates that a three-year program that serves 3,000 youth, works with six program providers, and pays youth a stipend of $12.50 per hour for 24 hours per week and six weeks per summer will cost $10 million each year—a total of $3,338 per youth participant. Compared to the social and economic price of gun homicides,2The cost of a gun homicide in the United States was obtained using the Everytown for Gun Safety Cost Calculator (2023). investing in an SYEP is a cost-effective way to help prevent violence in cities.

Relative Costs of SYEP Enrollment

$15.6M

Average Cost per Gun Homicide

$3,338

Average Cost per Youth in SYEP

“As a kid, I always wanted to work in city government, so seeing its inner workings really stuck with me, even now. In the Los Angeles Mayor’s Office of Gang Reduction and Youth Development, I helped families impacted by gun violence, worked with community organizers, participated in neighborhood events, and networked with city officials. I learned that it takes a village. As a rising college freshman, it made me even more excited for a political science major.”

—Emmanuel Macedo, Students Demand Action Summer Leadership Academy Alum

The Role of Summer Youth Employment in Reducing Violence

Governments and community members pay a steep price for persistent gun violence, including the costs of lives lost, police response, incarceration, medical care, and loss of income. Homicide rates across the United States have increased 35 percent since before the Covid-19 pandemic, posing an elevated and persistent public health crisis, and four out of every five homicides involve guns.1Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Health Statistics, CDC WONDER Online Database, Underlying Cause of Death, 2018–2021, https://wonder.cdc.gov/controller/datarequest/D158. This problem does not affect all Americans equally. Young men living in the country’s poorest urban communities suffer from the highest rates of gun homicides and nonfatal injuries, and interpersonal gun violence is often concentrated geographically and demographically among male adolescents, often in communities of color.2Kathryn Schnippel, Sarah Burd-Sharps, Ted R. Miller, Bruce A. Lawrence, and David I. Swedler, “Nonfatal Firearm Injuries by Intent in the United States: 2016-2018 Hospital Discharge Records from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project,” Western Journal of Emergency Medicine 22, no. 3 (2021): 462–70, https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2021.3.51925; Melissa Tracy, Anthony A. Braga, and Andrew V. Papachristos, “The Transmission of Gun and Other Weapon-Involved Violence Within Social Networks,” Epidemiologic Reviews 38, no. 1 (2016): 70–86, https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxv009.

What steps can cities take to prevent violence in their communities? A growing body of evidence highlights one promising intervention: summer youth employment programs (SYEPs) aimed at young people at risk for or with histories of violence. These programs match participating youth with jobs during the summer months, when violence is at its highest and many young people lack the structure and support that school ordinarily provides. SYEPs offer meaningful employment, safe spaces, and mentoring to young people, serving as a cost-effective intervention to prevent violence.

What Are the Benefits?

There are many potential advantages to establishing SYEPs: these programs can help prepare young people for college and careers, teach financial literacy, offer income support through paid work, improve school attendance and educational outcomes, and provide participants with a sense of agency, identity, and competency.3Kate O’Sullivan, Don Spangler, Thomas Showalter, and Rashaun Bennett, Job Training for Youth with Justice Involvement: A Toolkit (Washington, DC: National Youth Employment Coalition, 2020), 47; Financial Literacy and Education Commission, Resource Guide for Youth Employment Programs: Incorporating Financial Capability and Partnering with Financial Institutions (Washington, DC: US Department of the Treasury, 2017), https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/231/FLEC-Resource-Guide-for-Youth-Employment-Programs-January-2017-FINAL.pdf; Alexander Gelber, Adam Isen, and Judd B. Kessler, “The Effects of Youth Employment: Evidence from New York City Lotteries,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 131, no. 1 (2016): 423–460, https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjv034; Jacob Leos-Urbel, “What Is a Summer Job Worth? The Impact of Summer Youth Employment on Academic Outcomes,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 33, no. 4 (2014): 891–911, https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.21780; Alicia Sasser Modestino, “How Do Summer Youth Employment Programs Improve Criminal Justice Outcomes, and for Whom?,” Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 38, no. 3 (2019): 600–628, https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.22138. In addition to these broader benefits, studies of SYEPs in cities across the country show that these programs can help reduce violence, crime, and justice system involvement among participating young people.4Modestino, “How Do Summer Youth Employment Programs Improve Criminal Justice Outcomes, and for Whom?”; Judd B. Kessler, Sarah Tahamont, Alexander M. Gelber, and Adam Isen, “The Effects of Youth Employment on Crime: Evidence from New York City Lotteries” (NBER Working Paper 28373, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, 2021), https://doi.org/10.3386/w28373; Meghan Salas Atwell, Youngmin Cho, Claudia Coulton, and Tsui Chan, “The Impact of Summer Youth Employment (SYEP) in Cleveland on Criminal Justice and Educational Outcomes” (Briefly Stated Research Summary No. 20–01, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, February 2020), 6, https://case.edu/socialwork/povertycenter/sites/case.edu.povertycenter/files/2020-05/BrieflyStated_Feb_2020.pdf; Gelber, Isen, and Kessler, “The Effects of Youth Employment.” As just one example, a randomized control trial of Chicago’s SYEP found a 43 percent decrease in violent crime arrests among participants in the 16 months after they completed the program.5Sara B. Heller, “Summer Jobs Reduce Violence among Disadvantaged Youth,” Science 346, no. 6214 (2014): 1219–23, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1257809. SYEPs also offer safe spaces where youth are less likely to be victimized and counteract the structural racism that often denies young people of color pathways to meaningful employment. Programs can be effective at various levels of intervention—for example, both pre- and post-violence or justice system involvement—and research shows that benefits are felt particularly strongly by youth who have already been involved with the justice system.6Kessler et al., “The Effects of Youth Employment”; Katherine Tyson McCrea, Maryse Richards, Dakari Quimby, Darrick Scott, Lauren Davis, Sotonye Hart, Andre Thomas, and Symora Hopson, “Understanding Violence and Developing Resilience with African American Youth in High-Poverty, High-Crime Communities,” Children and Youth Services Review 99 (2019): 296–307, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.12.018.

↓43%

Chicago’s SYEP reduced violent arrests by 43% among participants 16 months post-program completion.

Sara B. Heller, “Summer Jobs Reduce Violence among Disadvantaged Youth,” Science 346, no. 6214 (2014): 1219–23, https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1257809.

While evaluations in the few years following these programs often show promising results, summer youth employment is not a magic wand that can wave away the multiple, often compounding, challenges youth at-risk of being involved with violence may face. Those problems—such as homelessness or housing instability, trouble with reading or simple math resulting from under-resourced schools, lack of access to culturally competent mental health care, and various forms of childhood trauma—are years in the making. Likewise, the solution will also require multiple forms of support over multiple years. A high-quality SYEP can make important contributions to overcoming these challenges. But it cannot be the only solution.

With this guide, Everytown aims to help cities and funders understand the key components and costs of implementing SYEPs. To make the process simpler, Everytown also developed and provides a costing tool that can be tailored to specific needs and budgets by adjusting for factors like cost of living, program size, inflation, specific outreach and support strategies, and more. This tool was developed using a rigorous methodology known as an ingredients approach from the bottom up, itemizing the key resources needed to implement an SYEP aimed at violence prevention.7For more information about the methodology employed to develop this costing tool, see https://everytownresearch.org/report/summer-youth-employment-programs/

Implementing an SYEP: Roles and Responsibilities

Who Do They Serve?

SYEPs are diverse and can target different populations based on program goals. Generally, programs whose goal is violence prevention prioritize recruiting participants from neighborhoods where youth are most impacted by violence, due to issues such as high crime, failing schools, and limited job opportunities. SYEPs are typically aimed at young people ages 14 to 24, at least some of whom face barriers to upward mobility, like living in low-income households, experiencing homelessness or housing instability, being involved in foster care or the justice system, or being pregnant or a parent.

Target neighborhoods might have:

- High crime

- Failing schools

- Limited jobs

- Housing instability

Who’s Involved?

A typical SYEP brings together a lead city agency to plan and oversee the program, SYEP provider organizations to train and work directly with young people, and employers to hire participants for the summer. Often, the employers are the cities or SYEP providers themselves—for example, a city might hire young people as lifeguards at a city pool or city park cleanup crews, while an SYEP provider might employ youth as summer camp counselors for younger children—but other organizations or businesses like private-sector retail or tech companies can also serve this role.

The lead city agency, usually a youth development or workforce development agency, is in charge of the program’s creation and execution. The city agency determines which populations and neighborhoods the program should prioritize. It also selects and contracts with the SYEP providers, working with them to recruit participants, advertise the program, and establish connections with other providers offering supplemental support and wraparound services as needed. The city agency is responsible for tasks such as producing the pre-employment training curriculum, providing the necessary data infrastructure to monitor the program, establishing and enforcing standard agreements for employers to have youth participate, and processing youth stipend payments.

The SYEP providers—which may be community-based organizations, nonprofit or for-profit organizations, universities, foundations, or other organizations—are in charge of the program’s on-the-ground implementation. The SYEP providers work directly with young people involved in the program, providing training, supervision, and mentoring for participants and connecting youth to wraparound support services as needed. SYEP providers also develop relationships with employers and coordinate with them to address any concerns or compliance issues.

The central role of employers is to introduce program participants to the working world and provide a safe and supportive work environment in accordance with program standards. To help with the recruitment and selection process, employers are responsible for documenting and describing available positions and tasks. Once the program is underway, employers supervise participants’ day-to-day activities, sign off on timesheets and communicate work absences to SYEP providers, allow SYEP provider staff visits, and notify SYEP providers when young people need additional support.

SYEP Organizational Structure

Lead City Agency

Example: Office of Youth Services, Office of Workforce Development

Role: advertise and oversee program, contract providers, run participant lottery, process payroll

SYEP Providers

Example: Community foundation or youth services nonprofit

Role: Implement program; recruit, refer, train, and support youth; conduct site visits; process timesheets and reports

Employers/Worksites

Example: Park services, summer camp, retail storefront, technology sector

Role: Provide safe, age-appropriate, and supervised employment; submit job descriptions; sign off on timesheets

Youth Participants

Age range: 14–24 years old

Target population: All youth in served communities, especially those at-risk of or with prior justice system contact

Implementing an SYEP: Calculating the Costs

The budget for an SYEP program can be divided into four major categories: staffing, training, equipment, and youth stipends, with an additional line for indirect costs. The total cost will depend on several factors, such as the number of youth served, the city’s minimum wage, and the length of the program. As an example, Everytown estimates that a three-year program that serves 3,000 youth, works with six program providers, and pays youth a stipend of $12.50 per hour8Minimum wages vary across states and range from $7.25 (the federal minimum wage) to $16.50 per hour. Research shows that higher minimum wages are associated with lower crime and violence rates. Eric D. Gould, Bruce A. Weinberg, and David B. Mustard, “Crime Rates and Local Labor Market Opportunities in the United States: 1979–1997,” Review of Economics and Statistics 84, no. 1 (2002): 45–61,

https://direct.mit.edu/rest/article-abstract/84/1/45/57295/Crime-Rates-and-Local-Labor-Market-Opportunities; “Consolidated Minimum Wage Table,” Wage and Hour Division, US Department of Labor, last revised January 1, 2023, https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/mw-consolidated; Council of Economic Advisors, Economic Perspectives on Incarceration and the Criminal Justice System (Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President of the United States, April 2016), https://web.archive.org/web/20160804151713/https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/page/files/20160423_cea_incarceration_criminal_justice.pdf. for 24 hours per week and six weeks per summer will cost $10 million each year—$3,338 per youth participant. To estimate the costs for your own program, you can use the SYEP costing tool to easily edit key program parameters such as the number of youth and the hourly wage.9To access the customizable costing tool, see https://everytownresearch.org/report/summer-youth-employment-programs/

Example SYEP Costing Breakdown

Key Costing Ingredients for City Agencies

- Staff: Staffing at the city agency will depend on program size and where the agency is housed in relation to other city departments. In our example, Everytown assumes that the SYEP will have a director, who is responsible for oversight, planning, curriculum development, and strategy; an assistant director, who leads the day-to-day operations of the program; and four data and administrative employees, who are in charge of tasks such as processing applications and submitting reports.

- Training and Materials: Training costs to the city agency are mostly for printed materials, such as a standardized workbook on workforce training provided to all the youth across the city or translation of materials into languages to be able to reach the targeted youth. Topics could include workplace etiquette, résumé and cover letter writing, financial literacy, conflict resolution, trauma-informed care, and hiring interview practice. The city agency may have additional recruitment costs such as flyers, brochures, public transportation advertisements, and online promotions.

- Equipment: The city agency’s equipment needs are limited to the office needs for staff, such as laptops or tablets and workspaces. Equipment costs should account for new programs, wear and tear, and loss and breakage.

Key Costing Ingredients for SYEP Providers

- Staff: A typical SYEP provider organization will require a program manager, a program assistant, youth employment specialists, team leads, and data entry staff. The level of staffing needed will depend on the number of youth served by the program and the intensity of support provided to them.

- Training: The SYEP provider offers workforce training to participants at the beginning of the summer, before employment begins, using curricula and materials produced by the city agency. This training usually takes place at the SYEP providers offices or a community space. Costs include materials for youth employment specialists and program participants such as pens, notepads, and flipcharts, and a lunch budget.

- Equipment: Similar to the lead city agency’s requirements, the equipment needed by SYEP providers includes laptops or tablets and workspaces for staff. This equipment should last for multiple years; however, the equipment budget should include the costs of replacement for loss and wear and tear, especially as staff are expected to frequently be out of the office supporting the youth. Other possible examples of equipment include a vehicle to transport team leads or youth to worksites or laptops that youth can use to submit applications, create résumés, or enter timesheets.

Youth Stipends

54¢

54¢ of every $1 invested in SYEPs is paid directly to youth.

Stipends paid directly to participating young people make up the largest share of the budget—54 cents for every dollar spent on the SYEP. While many summer programs and student internships may promote opportunities that rely on volunteer labor by the youth and, in doing so, avoid the cost of minimum-wage stipends, these programs create a major barrier for the young people most in need.10O’Sullivan, K., Spangler, D., Showalter, T., & Bennett, R. (2020). Job Training for Youth with Justice Involvement: A Toolkit (p. 47). National Youth Employment Coalition. In addition to an hourly wage, SYEPs may also want to invest in stipends for public transit to help youth travel to and from worksites.

A Focus on Violence Prevention

An SYEP aimed at reducing violence should explicitly prioritize neighborhoods where crime is concentrated. The mentoring and intensive support required for programs that serve young people at risk for or with histories of violence contributes to the estimated cost per youth in the example above. These costs can be higher in communities where additional supports are incorporated, based on need and resources. For example, New York City’s Emerging Leaders SYEP—aimed at homeless and runaway youth residing in shelters, justice-system- or court-involved youth, and youth in foster care or receiving support from child services—provides the most intensive support and the highest level of funding per youth. In our example, in order to lower participation barriers and offer the necessary support to young people in the program, the SYEP provider budget includes a team lead to mentor and support every 20 youth, lunch provided during training, and a public transit or transportation stipend on top of youth wages. While tailoring programs for young people with the greatest needs results in higher costs, SYEPs that focus on violence prevention may be most cost effective when considering the potential impact on public safety.

Download the Adjustable Costing Workbook

-

Methodological Note

The methods utilized in this report employ frameworks for economic analysis1Don Husereau, Michael Drummond, Stavros Petrou, Chris Carswell, David Moher, Dan Greenberg, Federico Augustovski, Andrew H. Briggs, Josephine Mauskopf, and Elizabeth Loder, “Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS)—Explanation and Elaboration: A Report of the ISPOR Health Economic Evaluation Publication Guidelines Good Reporting Practices Task Force,” Value in Health 16, no. 2 (2013): 231–50, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2013.02.002. and costing public2Administration for Children and Families, Cost Analysis in Program Evaluation: A Guide for Child Welfare Researchers and Service Providers (Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, 2013), 28; GAO, Cost Estimating and Assessment Guide: Best Practices for Developing and Managing Program Costs (Washington, DC: Government Accountability Office, 2020), https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-20-195g.pdf. or nonprofit3Nadini Persaud, “A Practical Framework and Model for Promoting Cost-Inclusive Evaluations,” Journal of MultiDisciplinary Evaluation 14, no. 30 (2018): 88–104. interventions. Costs are built using an ingredients approach from the bottom up, itemizing the key resources necessary to implement an SYEP with the goal of violence prevention. Unit costs were gathered by reviewing publicly available budgets and program reports for SYEPs that explicitly include youth who were justice-involved or at risk for violence (e.g., in Boston and New York City). Salary costs per month were estimated using OpenPayrolls.com information on average salaries for public-sector local employees in similar roles. Youth salary and stipend unit costs were entered as a factor of the minimum wage in order to adjust for locality differences. All costs are from the perspective of the organization or entity implementing the SYEP. Nonmonetary costs such as volunteer hours or in-kind donations of food, materials, or services are presented using their monetary value (replacement-cost approach) so that programs can plan for these resources if they are not available.

The costs and assumptions presented here are broken down by organization (i.e., lead city agency, SYEP providers, and employers, as well as youth participants ) and major budget category (i.e., staff, training, equipment, indirect costs, and stipends). They represent three years of funding and implementation, a period that often aligns with funding proposals, and present differences in the initial investment required compared to annual and recurrent costs. A 3.6 percent factor of annual inflation was included based on projections for 2023.4“March 22, 2023: FOMC Projections Materials, Accessible Version,” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, March 22, 2023, https://www.federalreserve.gov/monetarypolicy/fomcprojtabl20230322.htm. Units, unit costs, and formulas developed using the methods and assumptions described in the paper are both visible and editable in the supplementary workbook, where users can easily alter key program parameters such as wages and the number of youth served to have these cascade through other formulas as needed.

Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund would like to gratefully acknowledge Kathryn Bistline, formerly of Everytown, and Bruce Larson and Jonathan Jay, of Boston University, for their research and analytical contributions to this report.

Everytown Research & Policy is a program of Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, an independent, non-partisan organization dedicated to understanding and reducing gun violence. Everytown Research & Policy works to do so by conducting methodologically rigorous research, supporting evidence-based policies, and communicating this knowledge to the American public.