Dual Tragedies: Domestic Homicide-Suicides with a Firearm

Last Updated: 10.2.2025

Executive Summary

Content Warning: This report includes descriptions of intimate partner homicide-suicide with a gun and the experiences of victims and survivors, including children. Please take care. Help is available through the resources listed at the bottom of this report.

“My daughter was shot seven times while her 7- and 8-year-old daughters were there. . . . Then he [her ex-husband] shot and killed himself. And in an instant, everybody’s world was shattered. Even though they had been divorced for six years . . . it had to do with the kids and jealousy because he was estranged from his family. My daughter had a restraining order, and she had a stalking order against him. Their kids were seeing a counselor because of his erratic behavior. It was getting worse and worse.

Before the incident, there was a judge, there were attorneys, there were counselors, there were therapists, and he’d had an order to have his guns taken away. Nobody checked. It was multiple things, failures all around. And my husband said three months before it happened, ‘If anything ever happens, there’s red flags everywhere.’

After this, I stopped dreaming. Everything just went black and dark and stayed that way for a long time.”

A father killed his partner in front of his children, and then himself. This is called an intimate partner homicide-suicide (IPHS). These tragedies occur nearly every day in the United States,1Everytown Research analysis of NVDRS data from 2014 to 2020, accessed January 2025. and the impact is immeasurable. Surviving families mourn the loss of two family members, and in some cases the mass murder of a family. Children grapple with the loss of their parents while surviving family members become their new caretakers. Those who survive may live with wounds and trauma. And communities are fractured as they grapple with the grief and trauma that stems from these unimaginable tragedies. Moreover, the stigma associated with both suicide and intimate partner violence (IPV) leaves the details of many of these traumatic experiences untold.

To understand the frequency with which these tragedies occur and how we can better prevent them, Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund acquired and examined data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS)2The CDC’s National Violent Death Reporting System (NVDRS) is a state-based surveillance system that collects information from coroner or medical examiner reports, law enforcement reports, and death certificates on the circumstances and characteristics of violent deaths, including homicide and suicide. State participation in NVDRS has expanded over time, and the participating states vary by year. All states were included in this study with the exception of Florida due to insufficient data. Through a data use agreement, Everytown obtained records from the NVDRS Restricted Access Database for all female victims ages 13 and older of intimate partner homicides that occurred from 2014 through 2020. on all recorded intimate partner homicide-suicides of women by their male partners from 2014 to 2020. Behind these numbers are complex circumstances that lead up to these unthinkable tragedies. To bring attention to this, in 2024, we conducted focus groups with 43 survivors of intimate partner homicide-suicide. The focus group participants included people who survived an attempted intimate partner homicide-suicide, family members, and other individuals closely involved with the incident. This mixed methods research (MMR)3Mixed methods research (MMR) is a type of research that combines elements of qualitative and quantitative research approaches such as data collection, analysis, and inference techniques to gain an in-depth understanding of a phenomenon. R. B. Johnson, A. J. Onwuegbuzie, and L. A. Turner, “Toward a Definition of Mixed Methods Research,” Journal of Mixed Methods Research 1, no. 2(2007): 112–33, https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689806298224. paints a complete picture of these tragedies by documenting use of lethal means, as well as the complex emotional, social, and psychological factors that precede each dual-death.

In this report, we discuss the prevalence of IPHS nationally, the unique role of the accessibility of firearms, risk factors for IPHS, the impact on survivors and their families, and survivors’ experiences in accessing support services. We hope to honor the survivors who broke their silence and gave voice to the many lives forever changed by the dual tragedies of homicide-suicide.

Key Findings

-

Analysis of intimate partner homicide-suicides (IPHS) involving a firearm from 2014 to 2020 in the United States reveals that:

- A firearm was the primary weapon used in 85 percent of all IPHS, killing an average of 19 women each month.

- Women ages 45 and older were more likely to die by IPHS in comparison to intimate partner homicide.

- In states with the weakest gun safety laws, the IPHS rate was three times higher than in states with the strongest gun safety laws.

-

Analysis of focus groups with IPHS survivors in 2024 reveals that:

- There are 11 common risk factors associated with IPHS, collectively identified by survivors and family members, including access to a firearm, suicidal behaviors, and previous abuse.

- One in four IPHS perpetrators had a history of suicidal behaviors, such as suicide attempts and suicidal ideation.

- In nearly one in three IPHS incidents, the gun used was not securely stored and was readily accessible.

- According to survivors’ reports, nearly 25 percent of the perpetrators were prohibited by law from possessing a firearm for reasons including being under a domestic violence restraining order, having been convicted of a felony or misdemeanor domestic violence crime, or having certain mental health histories.1Everytown Research has not independently confirmed the prohibited status of the perpetrators.

- Children were witnesses in 43 percent of the IPHS with a firearm. As a result, they experienced immediate and long-term impacts such as suicidal ideation, actions of self-harm, academic challenges, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

What is intimate partner homicide-suicide (IPHS)?

A tragedy where a person kills their current or former intimate partner, their children, or other victims (e.g., a woman’s new partner) and then attempts or dies by suicide.

How often does intimate partner homicide-suicide with a firearm occur in the United States?

“My sister’s shooting occurred during a child handoff . . . Her kids and their grandfather were in the car when it occurred. . .After he shot her, my sister’s partner killed himself. She had recently decided she wanted to leave their marriage. When she made that known, he attempted strangulation. She then got a restraining order. . .However, he was able to travel to a different state, purchase a gun through a private sale, one not requiring a background check or anything. . .There were no safeguards to protect her.”

—Survivor whose sister was killed during an IPHS shooting.1The names of survivors in this report are pseudonyms in order to protect their confidentiality and identity. Everytown for Gun Safety has not independently reviewed the restraining order nor confirmed the state where the gun was purchased and therefore whether a background check was required under state law.

On that day, what should have been an uneventful caregiver transition turned into a crime scene. A painful trauma was created for this survivor, and for the children whose parents were ripped from their life. Sadly, we show that this story is one of many. Homicide-suicide occurs more than once a day on average in the United States, and intimate partner violence is the most common precursor to this particularly tragic form of gun violence.2Violence Policy Center, “American Roulette Murder-Suicide in the United States,” editions 4–8, https://vpc.org/revealing-the-impacts-of-gun-violence/murder-suicide/. A five-year average was developed using 2011, 2014, 2017, 2019, and 2021 data. An average of 187 intimate partner murder-suicide incidents occurred over six months, an estimated 374 annually.

In our analysis of NVDRS data from 2014 to 2020, we found that over 5,450 women were killed by an intimate partner. In one in three of these instances, the perpetrator then died by suicide themself. A firearm was used in 85 percent of all incidents of IPHS, killing nearly 1,600 women—these incidents make up nearly one in five of all gun homicides of women during this period.3Everytown Research analysis of NVDRS data, 2014–2020. Analysis includes firearm homicides involving females ages 13–85+ among participating states. Nearly all perpetrators of IPHS were men (99 percent) who killed their former or current intimate partners. Unfortunately, these numbers represent only a fraction of the reality due to poor data collection in some states.4NVDRS now includes all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. However, the quality and completeness of data collection vary by state due to differences in data-sharing policies, uneven resource allocation, and the lack of standardization in local practices and policies for medical and legal death investigators.

Intimate Partner Homicide-Suicides with a Firearm from 2014 to 2020

To compound these tragedies, intimate partners are often not the only lives cut short by IPHS. We found that nearly one in 10 incidents of IPHS involved the murder of the family’s children.5In addition to the intimate partner, 271 people were shot and killed in an IPHS. Of these victims, 142 were children ages 18 and younger. And among all incidents of IPHS, 8 percent saw the murder of two or more additional family members. Abusers who view their family members as possessions whom they control, or who lack boundaries between their identity and that of family members, may not want to leave their loved ones alive if they are preparing to take their own life.6Salvador Minuchin developed the concept of “enmeshment” to describe families in which boundaries between family members become blurred. As a result, they may start to lose their sense of autonomy and individual identity. Families and Family Therapy (Harvard University Press, 1974). The lethality and accessibility of firearms give abusers in suicidal crisis the ability to overpower and harm multiple people with little chance for intervention or survival.

In the aftermath of these incidents, survivors and family members must cope with their own trauma responses; tend to the needs of others, including children; and navigate support services and court systems. Families are fractured and communities struggle to understand why and how these tragedies could occur.

Who are the victims of intimate partner homicide-suicides with a firearm?

Women aged 45 and older—who are often in longer marriages or partnerships—experienced higher rates of IPHS compared to intimate partner homicides without suicides (IPH). This risk increases over a woman’s lifetime: women aged 75 and older died by homicide at rates nearly four times higher than IPH without suicides in the same age group. Caregiving represents a unique stressor and potential contributing factor for violence, particularly for elderly men who care for a partner with chronic illnesses. Elderly caregivers can experience a complex interplay of stress, mental health challenges, and hopelessness. Feelings of guilt can compound these stressors as they witness the decline of their partner’s health.7Gregory M. Zimmerman, Emma E. Fridel, and Kara McArdle, “Examining the Factors that Impact Suicide Following Heterosexual Intimate Partner Homicide,” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 38, no. 3-4 (February 2023), https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221104523. While intimate partner violence fuels many of these homicides, more research is needed to understand those motivated by aging and health conditions, which may more closely resemble double suicides than IPHS.

The risk of intimate partner homicide-suicide fluctuates for women as they age.

Intimate partner violence impacts families and communities of all races and ethnicities. However, the burden is not shared equally by all women. Our analysis of these tragedies from 2014 to 2020 shows that Black women saw rates of IPHS with a firearm that were 19 percent higher than white women. Pregnant or postpartum victims of gun IPHS are also disproportionately Black women, with rates nearly three times higher than white pregnant or postpartum women. The rate of IPHS with a firearm was also 9 percent higher for American Indian/Alaska Native women than white women. Women’s experiences of victim-blaming8Michele R. Decker et al., “‘You Do Not Think of Me as a Human Being’: Race and Gender Inequities Intersect to Discourage Police Reporting of Violence Against Women,” Journal of Urban Health 96 (2019): 772-83. and shame are compounded by chronic underresourcing of victim service providers and culturally specific resources that reduce IPV and lethal violence.9Corinne Peek-Asa et al., “Rural Disparity in Domestic Violence Prevalence and Access to Resources,” Journal of Women’s Health 20, no. 11 (November 2011): 1743–49, https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2011.2891; Danielle M. Davidov et al., “Intimate Partner Violence-Related Hospitalizations in Appalachia and the Non-Appalachian United States,” PLoS One 12, no. 9 (2017): e0184222, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0184222.

Black and American Indian/Alaska Native Women experienced the highest rates

of intimate partner homicide-suicide.

Access to a Gun: The Centerpiece of Dual Tragedies

“My sister’s husband . . . attempted strangulation. She got a restraining order. He then attempted suicide twice. At that time, she still had the active restraining order, but he was able to go to a different state and purchase a gun through a private sale.”10Everytown Research has not independently reviewed the restraining order nor confirmed the state where the gun was purchased and therefore whether a background check was required under state law.

—Survivor whose sister was killed by her partner

Access to a gun is the centerpiece of the dual tragedies of intimate partner homicide and suicide. The role of firearms in these tragedies is threefold: first, they are used as tools of power in abusive relationships to manipulate and control partners. Second, they are used to threaten or inflict harm or death. And third, using a gun is the most lethal form of suicide for people during a crisis.11Andrew Conner, Deborah Azrael, and Matthew Miller, “Suicide Case-Fatality Rates in the United States, 2007 to 2014: A Nationwide Population-Based Study,” Annals of Internal Medicine 171, no. 12 (2019): 885–95. Abusive partners may also threaten suicide with a firearm as a form of coercive control. Such threats can lead to impulsive and irreversible acts of violence. While IPHS is generally the result of many precipitating factors and a history of abuse, one of the most common factors in these incidents is that the offender had access to a gun and used it.12April M. Zeoli, “Multiple Victim Homicides, Mass Murders, and Homicide-Suicides as Domestic Violence Events,” Battered Women’s Justice Project, November 2018, https://www.preventdvgunviolence.org/multiple-killings-zeoli.pdf.

Impulsivity and Easy Access to Guns

In the focus groups, even though survivors often reported long-term intimate partner violence and other risk factors leading up to the incident, they consistently discussed the impulsive nature of IPHS, facilitated by easy access to a firearm. The “knee-jerk reaction” of carrying out IPHS resonated with survivors in the focus group as they described the moments before the incident. A survivor whose daughter was killed by their partner stated,

“I think it was a knee-jerk reaction. . . . The fiancé had a concealed-carry license [and] the gun was left out loaded and unlocked all of the time. And I know a hundred percent for sure that if that had not been the case, my daughter would be alive.”

Another survivor discussed how her partner died by suicide with an easily accessible gun:

“My first husband, a former Marine . . . had a suicide attempt right before we got married. . . . About a week after our second wedding anniversary, he had at some point gotten [the gun] out of the attic where it was stored, put it in the nightstand, and loaded it. I didn’t know that he did. And we got into an argument . . . and he pulled the gun out of his dresser.”

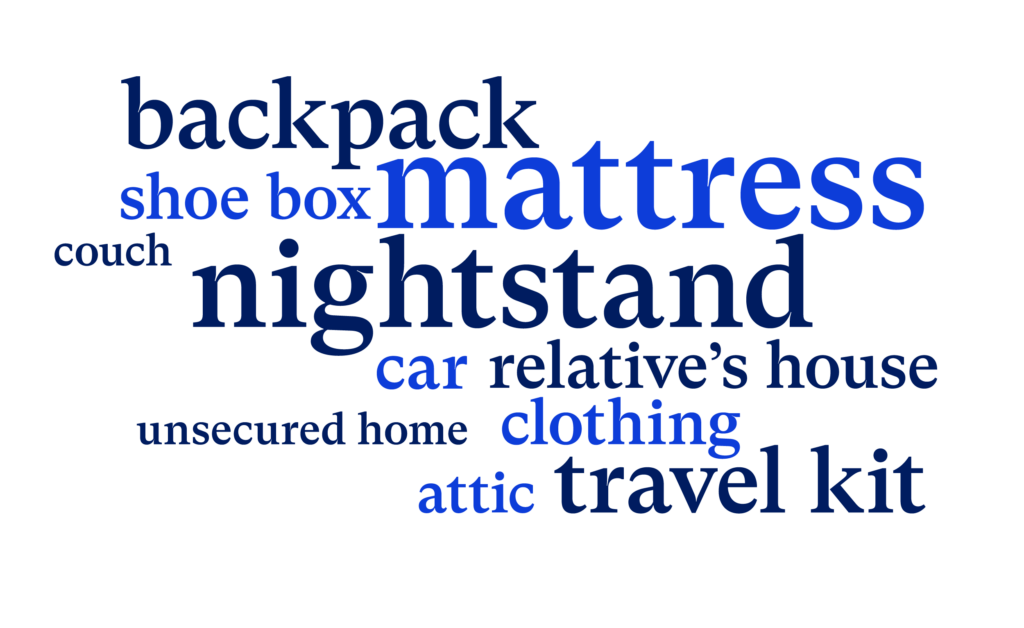

Where was the gun stored?

Thirty-two percent of survivors in the focus group stated that the gun used was easily accessible and stored unsecured. As with the incident described above, guns were often easily accessible in a nightstand, under the mattress, in the car, or unsecured at a family member’s house. Suicidal crises are often very brief, and access to a gun in a moment of crisis may be the difference between life and death for an individual; in the case of IPHS, easy access to a gun could mean the difference between life and death for multiple people.

Gaps in Gun Safety Policies and Implementation Failures

Many survivors in the focus groups revealed that, prior to the incident, offenders threatened family members and the victim that they would use a firearm for IPHS. In addition, the survivors highlighted signs that the perpetrator was a danger to themselves or others, describing behaviors such as suicidal ideation, stalking, and abuse within the relationship between the victim and the perpetrator. In response to these threats and actions, family members took various steps, including contacting their local police department to remove access to a gun, obtaining restraining orders, and seeking support from lawyers. However, survivors and their families faced a number of challenges, including difficulty accessing legal interventions and the judiciary and law enforcement’s failure to enforce laws. These challenges ultimately enabled abusers to retain access to guns, with devastating effects.

A mother whose daughter was killed described the multiple failures among institutions and support services:

“My daughter had a restraining order and she had a stalking order against him, and their kids and her were seeing a counselor because of his erratic behavior. It was getting worse and worse. . . . He’d had an order to have his guns taken away. Nobody checked. It was multiple things, failures all around.”

Laws that disarm abusers do not implement themselves. Mothers, partners, and family members in the focus groups spoke about the various “red flags” raised and the lack of adequate action from service providers and court systems to guard the safety of the victim and their children.

Challenges Accessing Legal Interventions

In response to firearm threats and dangerous behaviors, family members attempted to remove access to guns through an extreme risk protection order (ERPO) and obtain a domestic violence restraining order (DVRO), which may include several vital protections, such as ordering the abuser to stay away from the survivor and housing and child custody provisions. However, when survivors sought protection through a DVRO or an ERPO, they were often met with myriad challenges, such as stigmatization from law enforcement and the courts and bureaucratic barriers. For example, a survivor whose partner attempted to kill her before he died by suicide described the difficulties in obtaining a DVRO:

“I couldn’t get a protective order because there was really nothing rising. He was stalking me, but it’s also really hard to get a protective order for somebody stalking you who’s married to you. . . . So it really was difficult to get any help. I couldn’t call the police. There were really no resources for me.”

Research shows that states that prohibit abusers subject to DVROs from possessing firearms have seen a 13 percent reduction in intimate partner firearm homicide rates,13April Zeoli et al., “Analysis of the Strength of Legal Firearms Restrictions for Perpetrators of Domestic Violence and Their Associations with Intimate Partner Homicide,” American Journal of Epidemiology 187, no. 11 (November 2018): 2365–71, https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwy174. and studies in Indiana and Connecticut estimate that one suicide is prevented for every 10 to 11 firearm removals under Extreme Risk laws.14Aaron J. Kivisto and Peter Lee Phalen, “Effects of Risk-Based Firearm Seizure Laws in Connecticut and Indiana on Suicide Rates, 1981–2015,” Psychiatric Services 69, no. 8 (August 2018): 855–62, https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201700250. The recent US Supreme Court decision in United States v. Rahimi,15Everytown for Gun Safety, “United States v. Rahimi,” https://www.everytown.org/rahimi-scotus/. which ruled the federal law prohibiting domestic abusers subject to DVROs from possessing guns is constitutional under the Second Amendment, is crucial for IPV victims, survivors, and their families. This decision makes it clear that guns do not belong in the hands of domestic abusers.

Histories of Stalking and Loopholes in the Law

Ten percent of survivors in the focus groups stated that perpetrators engaged in stalking behaviors before the homicide-suicide or attempted homicide-suicide. A survivor whose mother died by IPHS discussed this:

“There was a lot of stalking and harassment behavior that went on. She did get a restraining order, and it was even extreme enough that at least in the state of Florida, they put a GPS tracker on him to keep him away from her. But eventually, the judge lifted that order and a few weeks later he bought a gun online and then murdered her.”

Violent and harassing stalking behaviors often occur alongside physical, emotional, and psychological abuse—contributing to fear of future serious harm or death.16Mindy B. Mechanic, Terri L. Weaver, and Patricia A. Resick, “Intimate Partner Violence and Stalking Behavior: Exploration of Patterns and Correlates in a Sample of Acutely Battered Women,” Violence and Victims 15, no. 1 (Spring 2000): 55–72, https://doi.org/10.1891/0886-6708.15.1.55. Stalking is a strong risk factor for intimate partner homicide: one study found that 76 percent of intimate partner homicides and 85 percent of attempted homicides of women were preceded by at least one incident of stalking in the year before the attack.17Judith MacFarlane et al., “Stalking and Intimate Partner Femicide,” Homicide Studies 3, no. 4 (November 1999): 300–316, https://doi.org/10.1177/10887679990. Yet federal law only bars those convicted of felony stalking from obtaining a firearm—not those with misdemeanor stalking convictions. Fewer than half of states have closed this loophole by either classifying stalking as a felony offense or by extending prohibiting offenses for accessing firearms to include specified misdemeanors.18 As of May 2024, 21 states prohibited people with stalking convictions from having firearms. Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, “Everytown Gun Law Rankings: Which States Prohibit People with Stalking Convictions from Having Firearms?,” accessed May 29, 2024, https://everytownresearch.org/rankings/law/stalker-prohibitor/.

Failure to Block Gun Access from Prohibited Perpetrators

-

WHAT IS FAMILY ANNIHILATION?

Family annihilation is any event where a person kills two or more family members, such as their partner or children, before killing themselves.

Even when survivors had access to and sought protections and petitioned a court for an order to temporarily prevent someone in crisis from accessing guns, the judicial system and law enforcement frequently failed to protect survivors and enforce lifesaving laws, including preventing perpetrators prohibited from having guns from accessing them. In our focus groups, survivors stated that nearly 25 percent of the perpetrators were prohibited by law from possessing a firearm,19Everytown Research has not independently confirmed the prohibited status of the perpetrators. for reasons including being under a domestic violence restraining order, having been convicted of a felony or misdemeanor domestic violence crime, or having certain mental health histories. A survivor whose sister and nephew died in a family annihilation followed by suicide discussed this:

“He [the perpetrator] wasn’t supposed to have a gun due to being a convicted felon. But I was later informed by one of my sister’s friends that he had multiple guns and actually held her and the kids as hostages a few weeks before the shooting incident.”

This family continues to struggle with the loss of their loved ones, and the question, “How did he access a gun?” remains. The reality is that far too often, people who are legally prohibited from having guns are able to evade background checks and purchase firearms with no questions asked. Each year, on average, at least one in eight prohibited purchasers of firearms who are denied the purchase through a background check are denied due to prohibiting domestic violence histories.20US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), “Publications & Products: Background Checks for Firearm Transfers,” https://bit.ly/2F4vMYw. Data on federal- and state-level denials were obtained from the BJS reports for the years 1999–2010 and 2012–2020. Local-level denials were available and included only for the years 2012, 2014–2018, and 2020 from the BJS reports. Data for the years 2011 and 2021 were obtained by Everytown Research from the FBI directly. Though the majority of the transactions and denials reported by the FBI and BJS are associated with a firearm sale or transfer, a small number may be for concealed-carry permits and other reasons not related to a sale or transfer. Totals include both those who are prohibited due to a misdemeanor crime of domestic violence (MCDV) conviction and those who are denied due to restraining or protection orders for domestic violence. According to survivors in the focus groups, in too many cases, no one ensured that the centerpiece of this tragedy—the gun—was removed when the perpetrator became legally prohibited from having it.

Risk Factors and Impact of Intimate Partner Homicide-Suicide

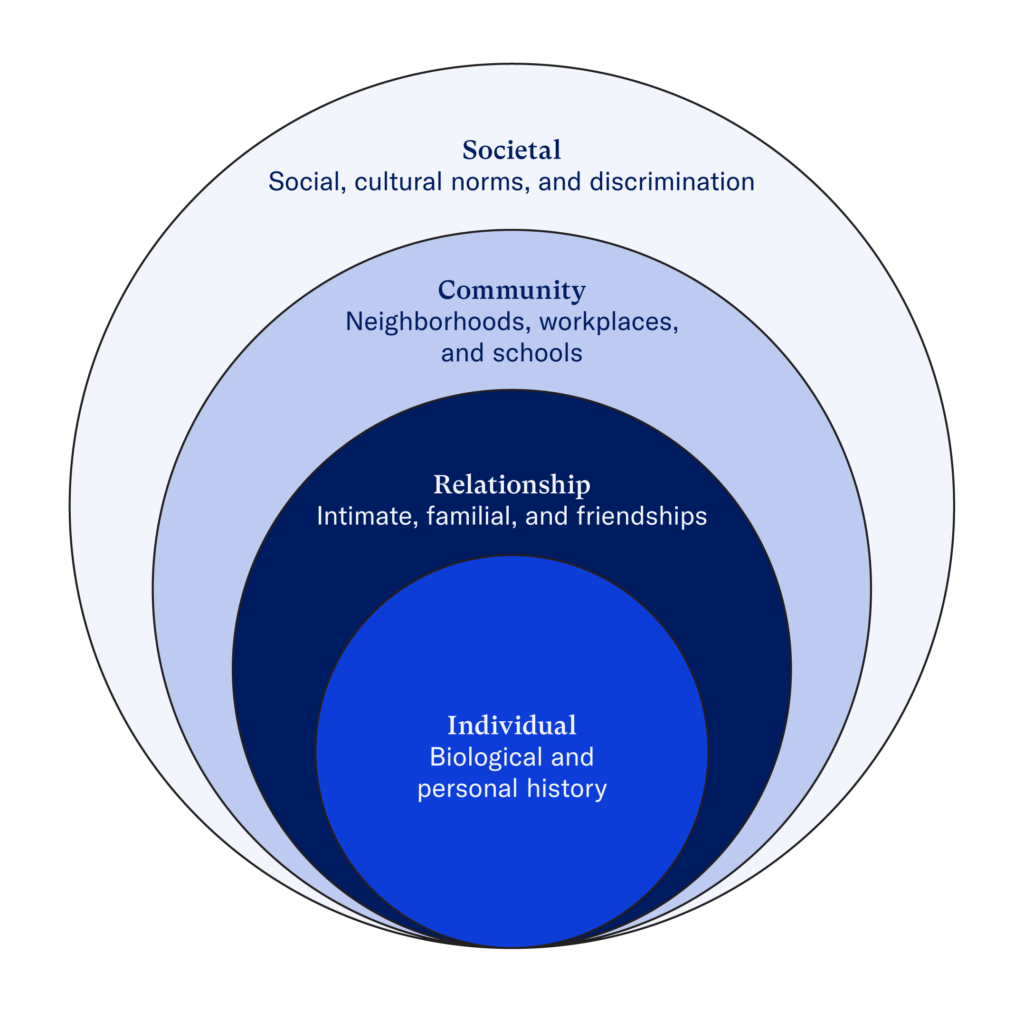

There is no excuse for abuse. Recognizing the risk factors leading up to an IPHS incident is critical in order to understand how to prevent these unimaginable tragedies. We adapted a model for looking at risk factors that contribute to violence and victimization at the individual, relationship, community, and societal level. This is called the socio-ecological model.21 Developmental psychologist Urie Bronfenbrenner originally theorized an ecological model to examine human development. See Urie Bronfenbrenner, “Ecological Systems Theory,” in Encyclopedia of Psychology, vol. 3, ed. A. E. Kazin (Oxford University Press, 2000), 129–33, http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/10518-046.

| Risk Factors and Protective Factors: The Socio-Ecological Model | |

|---|---|

| Individual Biological and personal history | Individual-level factors include substance misuse, history of abuse, education, income, and age. |

| Relationship Intimate, familial, and friendships | Relationship-level factors include conflicts such as jealousy, divorce, separation, and unhealthy or harmful familial relationships. |

| Community Neighborhoods, workplaces, and schools | Community-level factors include neighborhood poverty, residential segregation, and high density of alcohol outlets. |

| Societal Social, cultural norms, and discrimination | Societal factors include stigma; educational, economic, and health policies and practices that maintain social inequities, as well as accessibility of firearms; and gun laws and policies. |

We find that the dual tragedies of intimate partner homicide-suicide can occur amid warning signs and risk factors. In the focus groups, all survivors of IPHS identified one or more of these 11 common risk factors:

- Access to a firearm

- Previous abuse in the relationship, such as verbal, emotional, or physical abuse

- Threats against children and family members

- History of traumatic events (e.g., childhood exposure to violence)

- Suicidal behaviors, such as suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and threats of suicide

- Divorce or separation

- Jealousy

- Stalking

- Abuse through technology

- Substance misuse

- Social isolation

Our analysis of IPHS from 2014 to 2020 found similar risk factors at all levels, including alcohol use, substance misuse, mental health challenges, and perpetrators’ recent contact with a psychiatric facility and hospitals.

Individual-Level Factors

Various individual-level factors increase a person’s risk of becoming a victim or perpetrator of violence. Note, however, that perpetrating abuse is never justified, regardless of the circumstances in a person’s life. Focus group findings on individual-level factors were supported by research showing that exposure to violence during childhood is a risk factor for experiencing and perpetrating IPV in adulthood.22Diana Gil-González et al., “Childhood Experiences of Violence in Perpetrators as a Risk Factor of Intimate Partner Violence: A Systematic Review,” Journal of Public Health 30, no. 1 (January 2008): 14–22, https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdm071; Angela J. Narayan et al., “The Legacy of Early Childhood Violence Exposure to Adulthood Intimate Partner Violence: Variable- and Person-Oriented Evidence,” Journal of Family Psychology 3, no. 7 (2017): 833–43, https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000327; Margot Shields et al., “Exposure to Family Violence from Childhood to Adulthood,” BMC Public Health 20, no. 1673 (2020), https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09709-y. Such violence can include physical abuse, emotional abuse, neglect, witnessing parental IPV, and a history of suicidal behavior. A survivor discusses how exposure to violence played a role before the incident:

“His background included being abused as a child, and he went through a horrible divorce with his parents, and there were substance use issues, and he wasn’t getting treated or dealing with any of those issues.”

Survivors also shared that intimate partner violence between their parents led to their own aggressive and violent behaviors in adulthood. Moreover, exposure to trauma during childhood also led survivors down a path of being in abusive relationships. For example, one focus group participant stated that her daughter died by IPH, and while the survivor was pregnant with her now-deceased daughter, the survivor’s mother also died by IPHS. This survivor discussed the impact on her daughter:

“So she was very traumatized in her life knowing the fact that she was there when it happened. . . . She was really, really traumatized by that. And she chose really bad men because of that. I think she felt almost guilty.”

Exposure to the dual tragedies of IPHS experienced by her mother impacted the daughter throughout her life as she experienced trauma, feelings of guilt, and unhealthy relationships. Trauma from witnessing or experiencing abuse can be passed down across generations, a cycle called intergenerational trauma. Additionally, children who are exposed to multiple forms of violence—such as suicide, homicide, and IPV—are more likely to exhibit higher levels of distress and experience a greater risk of depression, anxiety, and PTSD.23David Finkelhor et al., “Polyvictimization: Children’s Exposure to Multiple Types of Violence, Crime, and Abuse,” National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence 39 (2011): 24–34, https://scholars.unh.edu/ccrc/25/.

Substance misuse was another prevalent individual-level risk factor. Focus group participants described substance misuse as both a risk factor leading up to the tragedies and a coping strategy. One survivor whose mother was killed by intimate partner homicide and whose father died by suicide stated,

“When I was a small child, my father was a raging alcoholic and very abusive, and my parents argued a lot. In that particular room, my mother was laying in bed and he was standing over her with a shotgun that we owned because he did hunting.”

This survivor witnessed her father’s substance misuse and alcohol dependence and how they factored into her mother’s abuse. Twenty-four percent of survivors and families of IPHS victims observed substance misuse or alcohol dependence prior to the incident. This finding aligns with previous studies: substance misuse and alcohol dependence are a risk factor for suicide and IPV, either as a victim or perpetrator.24Deborah M. Capaldi et al., “A Systematic Review of Risk Factors for Intimate Partner Violence,” Partner Abuse 3, no. 2 (April 2012): 231–80, https://doi.org/10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.231; Yari Gvion and Yossi Levi-Belz, “Serious Suicide Attempts: Systematic Review of Psychological Risk Factors,” Frontiers in Psychiatry 9 (March 6, 2018), https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00056. In fact, one study found that nearly 38 percent of IPHS perpetrators who were tested for alcohol at the time of the incident tested positive.25Joseph E. Logan, Allison Ertl, and Robert Bossarte, “Correlates of Intimate Partner Homicide among Male Suicide Decedents with Known Intimate Partner Problems,” Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 49, no. 6 (June 12, 2019): 1693–706, https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12567.

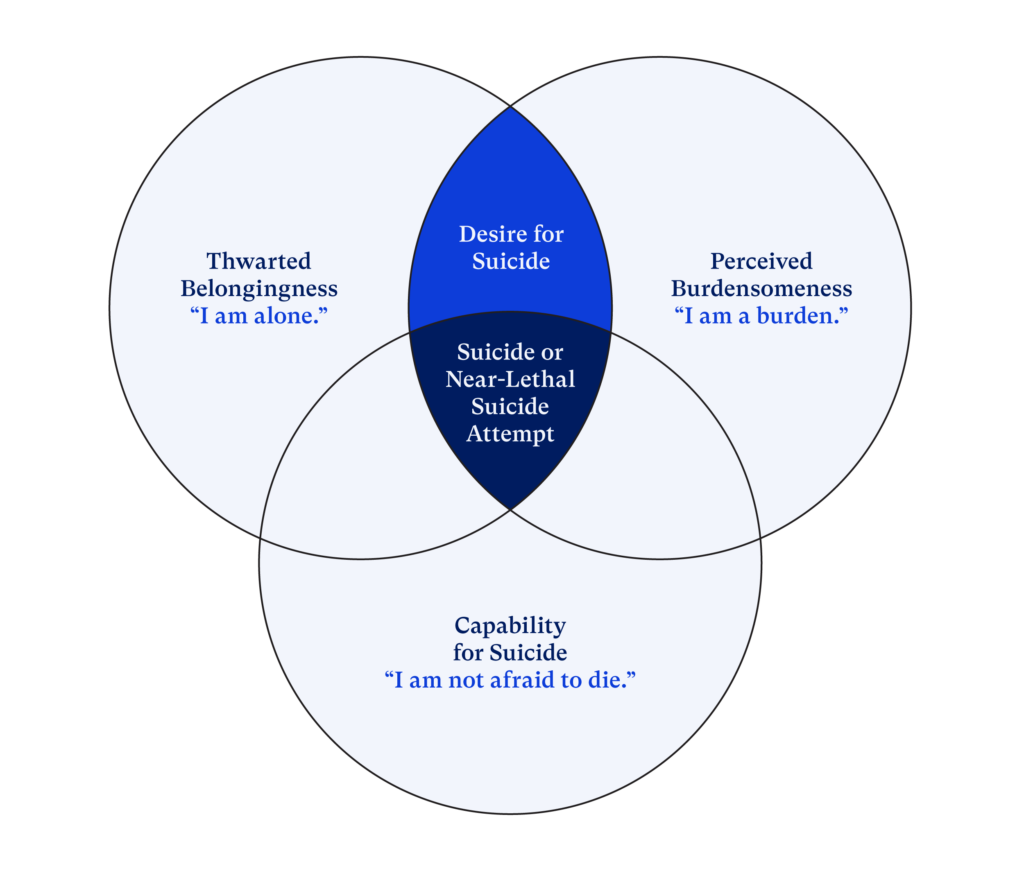

Joiner’s Theory of Suicide

While studies have focused on the mental health and substance misuse histories of people who died by IPHS, little is known about their previous suicidal behaviors, such as suicidal ideation, attempted suicide, and threats of suicide. In the focus groups, nearly 25 percent of IPHS perpetrators had a history of suicidal behavior. A survivor of attempted IPHS described her partner’s suicidal behavior:

“He had threatened suicide when we were still together when I was even pregnant with our daughter. . . . And he said he had nothing to live for and that he was just going to go kill himself. . . . He had threatened suicide by cop before. And I think just the fact that I wasn’t going to be taking him back and he was making the whole divorce process as ugly as possible, I think that kind of was the tipping point for him.”

This survivor’s husband threatened suicide multiple times before the incident, especially during stressful events. Suicidal ideation and attempts are connected with other risk factors, such as relationship-level issues, financial stressors, poverty, and lack of health care. These factors contribute to Thomas Joiner’s three primary components of suicide:26Thomas Joiner, Why People Die by Suicide (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005).

- Perceived burdensomeness, such as feeling that one’s partner or family would be happier or better off without them.

- Thwarted belongingness, such as feeling isolated and disconnected from others and from social environments.

- A build-up of lethality and fearlessness through the loss of fear of death and self-harm and suicide attempts.

Survivors of attempted IPH recalled such feelings among their partners. Simultaneously, another common aspect of intimate partner violence is that the abusive partners ensured that their victims were disconnected from family and social support networks. Abusive partners would also make the victim feel like a burden due to economic dependence and by lowering their self-esteem.

Relationship-Level Factors

Focus group participants also reported various relationship-level factors present before the IPHS incident. These factors included unhealthy family relationships, jealousy, possessiveness, and divorce or separation. Many of the participants who referenced divorce or separation also discussed the challenges of seeking custody of the children they shared with the perpetrator. A survivor whose daughter was killed in a homicide-suicide explained,

“My second husband was an abuser and we had a two-year-old daughter together. And when I realized that he was an abuser, because I didn’t realize it at the beginning, I finally got him moved out of the house. A few months later he murdered our two-year-old daughter and committed suicide.”

In this tragedy, separation was a key factor leading up to the father’s fatal actions. Separation between partners also increases the risk of lethality for the woman.27Kathryn J. Spearman et al., “Firearms and Post‐separation Abuse: Providing Context behind the Data on Firearms and Intimate Partner Violence,” Journal of Advanced Nursing 80, no. 4 (2024): 1484–96, https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15933. In the focus group, for nearly 50 percent of survivors, separation or divorce was a circumstance leading up to the incident. Research also shows that parental IPV and a perpetrator’s history of suicidal behaviors are both risk factors for child homicides.28Vivian Lyons et al., “Risk Factors for Child Death During an Intimate Partner Homicide: A Case-Control Study,” Child Maltreatment 26, no. 4 (2021):, 356–62, https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559520983901. Barriers to safety following a separation can turn deadly as women negotiate family court and co-parenting arrangements, navigate coercive control and tactics such as stalking and technological harassment, and face economic barriers to safety.29Kathryn Spearman et al., “Addressing Intimate Partner Violence and Child Maltreatment: Challenges and Opportunities,” Handbook of Child Maltreatment (2022): 327–49, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-82479-2_16; Kathyrn Spearman, Jennifer Hardesty, and Jacquelyn Campbell, “Post‐separation Abuse: A Concept Analysis,” Journal of Advanced Nursing 79, no. 4 (2023): 1225–46, https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15310.

-

WHAT IS COERCIVE CONTROL?

Coercive control is a pattern of behavior in which one person establishes dominance over another through isolation, intimidation, threats of violence, and physical violence. People who experience coercive control are often isolated from their friends, family, and support networks and are fearful for their safety, even in the absence of physical violence.

Prior abuse by the perpetrator served as another risk factor for homicide-suicides.30Bernie Auchter, “Men Who Murder Their Families: What the Research Tells Us,” NIJ Journal 266 (2010). In fact, 59 percent of victims or survivors in the focus group endured short- and long-term abuse before the incident. A survivor recalled the long-term abuse perpetrated by her father before the homicide-suicide incident that killed both her parents:

“My father . . . worked in law enforcement and had many guns. . . . He used them to intimidate his family. . . . He abused us. . . . He threatened to kill my mom several times and to kill me.”

Survivors in the focus group echoed these experiences of threat with a firearm. Previous studies on intimate partner homicides have found that perpetrators had feelings of jealousy,31Laura Johnson, “Jealousy as a Correlate of Intimate Partner Homicide-Suicide versus Homicide-Only Cases: National Violent Death Reporting System, 2016–2020,” Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior, March 30, 2024, https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.13076. monitored victims’ behaviors through the use of technology, and expressed attitudes of ownership and possessiveness.32 Jane Koziol-Mclain et al., “Risk Factors for Femicide-Suicide in Abusive Relationships: Results from a Multisite Case Control Study,” Violence and Victims 21, no. 1 (February 1, 2006): 3–21, https://doi.org/10.1891/vivi.21.1.3. Multiple focus group participants shared that before the incident, offenders stated, “If I can’t have you, no one can.” These behaviors were compounded by repeated breakups. Support services and interventions on the relationship level should acknowledge the heightened risk when a person is ending an abusive relationship.

Social stigma around intimate partner violence and suicide can make survivors hesitant to speak about the tragedy with family members and friends. One woman whose partner died by suicide after he attempted to take her life described the impact on some of her relationships:

“There was, especially on his side of the family, a lot of anger—a lot of wanting to place blame, avoidance, and a lot of silence from my side of the family. There wasn’t a lot of coming together and healing. It was [the] complete opposite. And because of that, I don’t really know how anyone is doing. Nobody talks about it, and I don’t talk to his family. It’s been eight years, almost nine.”

As people grapple with pain, conflict, stigma, and trauma, relationships can become strained, fractured, and end. “Blame, avoidance, and a lot of silence” can produce feelings of anger and guilt that make it difficult to cope in the aftermath. Silence surrounding the tragedy can create barriers to healing and accessing support services.

Community-Level Factors

Various community-level factors can increase or decrease someone’s likelihood of experiencing or perpetrating intimate partner violence. Research has shown that community risk factors for IPV include exposure to high rates of violence and crime, limited support services, social isolation from community residents, and weak community sanctions against IPV—such as the unwillingness of neighbors and law enforcement to intervene in violent situations.33Capaldi et al., “A Systematic Review of Risk Factors for Intimate Partner Violence.”

Living in a rural area can heighten existing challenges for survivors. Rural residents have less access to support services such as local domestic violence shelters or community-based organizations. Rural survivors in the focus group experienced less effective responses from law enforcement compared to those who lived in urban communities. And even when support services were accessible, they were limited. For example, a rural survivor of attempted IPHS stated that when her husband became verbally abusive, she contacted a local domestic shelter in her community, which told her, “Well, you don’t meet the criteria to leave with your kids,” without offering other resources or options to exit the abusive relationship. Research has shown that rural women are nearly twice as likely to be turned away from services because of inadequate staffing and a limited number of programs for survivors.34Radha Iyengar and Lindsay Sabik, “The Dangerous Shortage of Domestic Violence Services,” Health Affairs 28, Supplement 1 (January 2009): w1052–w1065, https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.28.6.w1052. In addition, long response times from law enforcement can deter survivors from reporting. A mother who constantly told her daughter to call the police if she felt unsafe stated,

“My daughter had a restraining order, and he would text her very mean things and leave very nasty voicemails to her. And I’m like, ‘Hey, he’s not supposed to have any contact with you. You need to call the police.’ But it would take the police a long time to get there. So, she didn’t think that they would come.”

In these experiences, social isolation became a barrier to seeking help and receiving an effective response from law enforcement. Research has shown that people who reported limited social connections in a community experienced higher rates of IPV,35Elizabeth Schreiber and Emily Georgia Salivar, “Using a Vulnerability-Stress-Adaptation Framework to Model Intimate Partner Violence Risk Factors in Late Life: A Systematic Review,” Aggression and Violent Behavior 57 (2021): 101493. and the focus group survivors stated that this influenced the lack of intervention from community members. A survivor who described the death of her neighbor by IPHS stated, “He [the perpetrator] had been very abusive to his wife and the kids. . . . Our whole neighborhood was watching what was going on behind a closed door.” Intimate partner violence should be a community-level concern, and neighborhood bystander intervention and local community-based resources can interrupt harmful situations. Such interventions also help those at risk to access services, heal, and connect with a supportive community—leading to safety.

Survivors discussed the importance of such social support as communities navigate collective trauma following the tragedies: feelings of hopelessness, hypervigilance, and fear. Such exposure to trauma can also increase the risk of future violence in the community. A survivor whose brother and mother were shot and killed discussed the importance of community support during a traumatic event:

“These are two people that I cared deeply for and I wanted to get that message [out there], and [the media outlet] was very helpful in that. And then the broader community in our hometown really came out in support as well. And that was great. It really showed me how much other people’s lives were touched by my mom and my brother.”

Social support as a protective factor can reduce negative psychological symptoms, such as self-harm and PTSD, and promote post-trauma resilience and recovery.36Brooke Feeney and Nancy Collins, “A New Look at Social Support: A Theoretical Perspective on Thriving through Relationships,” Personality and Social Psychology Review 19, no. 2 (August 14, 2014): 113–47, https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314544222; Casey Calhoun et al., “The Role of Social Support in Coping with Psychological Trauma: An Integrated Biopsychosocial Model for Posttraumatic Stress Recovery,” Psychiatric Quarterly 93, no. 4 (October 5, 2022): 949–70, https://doi.org/10.1007/s11126-022-10003-w. Healing happens when members of the community acknowledge the impact of the tragedy, collectively mourn, and create pathways to resources and social support for all individuals affected.

Societal-Level Factors

Stigma and Silence

In addition to experiencing stigma from family members, survivors also faced stigmatization at the societal level. Traditional gender norms surrounding masculinity and femininity, racial discrimination, and sexism are embedded within societal factors that contribute to IPHS—and, in turn, prevent survivors from seeking intervention or mental health support services and reporting their abuse.

The societal perception of IPV often revolves around the belief that partner abuse is provoked or that IPV survivors willingly stay in abusive situations. For example, one survivor stated that when she attended her court hearing for a DVRO, “The judge asked me if I deserved to be shot.” This survivor later stated, “I’m a BIPOC woman, Black, white, and Native. . . . My perpetrator was white, so of course the system took his side and made him the victim.” Dismissal of her IPV experience negatively impacted the implementation of laws that prohibit abusers’ access to guns. At a time when she faced a heightened risk, the system failed her.

The pervasiveness of self-blame and shame accompanying IPV may lead to deadly consequences and a culture of silence. A survivor of family annihilation murder-suicide discussed the impact of being silenced:

“When women finally ask for help—because we don’t always ask for help—we ask for help when it’s too late. . . . As domestic violence survivors, we downplay the situation. We don’t want to cause drama or we know we’re not going to be believed, or the person, the domestic abuser, is really very charming to other people.”

Survivors anticipate the stigma they would endure from responders such as law enforcement, healthcare providers, and others.37Nicole M. Overstreet and Diane M. Quinn, “The Intimate Partner Violence Stigmatization Model and Barriers to Help-Seeking,” Basic and Applied Social Psychology 35, no. 1 (January 1, 2013): 109–22, https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2012.746599.

As a result, survivors are discouraged from reporting their abuse or seeking interventions and protections, often downplaying the situation. Black and Latinx women in the focus group were often blamed for their abuse due to racial and gender-based stereotypes of promiscuity. In addition, the perception that Asian American and Native American women are submissive led to a dismissal of their IPV experiences. These experiences mirror our findings of the disproportionate burden of IPHS on Black and American Indian/Alaska Native women nationally.

While shame, stigma, and fear can limit women’s engagement with health services and the judicial system, according to focus group participants, men also experienced stigma when seeking mental healthcare services. Survivors mentioned various short- and long-term interventions that men sought, such as therapy from community-based organizations and visiting state mental health hospitals and psychiatric treatment centers. However, when men sought it, that care felt short. A survivor whose brother died by suicide following family annihilation describes the mental health care his brother received:

“After his second attempt, it was just sort of a procedure with being found by the police and he had to go to a state mental health hospital, which they kept him for three days and then said that he was fine and not a threat to anybody. He indicated that none of those things ever did anything for him.”

Men in the United States represent 87 percent of firearm suicide victims and are nearly seven times more likely than women to die by firearm suicide.38Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, WONDER Online Database, Underlying Cause of Death. A yearly average was developed using five years of the most recent available data: 2018 to 2022. White defined as non-Latinx origin. Yet men are less likely to seek help for mental health difficulties.39Ilyas Sagar-Ouriaghli et al., “Improving Mental Health Service Utilization among Men: A Systematic Review and Synthesis of Behavior Change Techniques within Interventions Targeting Help-Seeking,” American Journal of Men’s Health 13, no. 3 (May 2019): 155798831985700, https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988319857009. Why is this? Research has shown that men’s help-seeking behaviors for mental health support for issues such as depression are influenced by societal norms surrounding masculinity, such as expectations that men should be strong, self-reliant, and in control, and should avoid expressing their emotions.40Silvia Krumm et al., “Men’s Views on Depression: A Systematic Review and Metasynthesis of Qualitative Research,” Psychopathology 50, no. 2 (March 11, 2017): 107–24, https://doi.org/10.1159/000455256. The pressures to conform to these norms discourage men from seeking support, stigmatize their help-seeking behaviors, influence their silence, and may lead to unhealthy coping strategies such as substance misuse.

When men do seek help, providers’ own gender biases may lead them to underestimate men’s needs and miss or misdiagnose their psychological issues.41Paul Sharp et al., “‘People Say Men Don’t Talk, Well That’s Bullshit’: A Focus Group Study Exploring Challenges and Opportunities for Men’s Mental Health Promotion,” PLoS One 17, no. 1 (January 21, 2022), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261997. In fact, our analysis of IPHS incidents from 2014 to 2020 shows that there were missed opportunities to support men: In nearly 10 percent of these tragedies, the suspect had recent contact with the police or was recently released from jail, a hospital, psychiatric facility, residential treatment program, or other type of institution. Court and healthcare systems can be intervention points, and recent contact with these systems indicates that there were multiple missed opportunities for intervention in many incidents of IPHS.

In the Aftermath of IPHS

All survivors in this study experienced trauma, which refers to the lasting adverse effects of an event or a culmination of a series of events. Trauma’s impact is beyond measure—rippling through families and communities. Research shows that people who experienced threats with a gun during incidents of domestic violence had more psychological symptoms than women who experienced other forms of IPV victimization, such as mental, emotional, and sexual types of abuse.42Tami P. Sullivan and Nicole H. Weiss, “Is Firearm Threat in Intimate Relationships Associated with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptoms among Women?,” Violence and Gender 4, no. 2 (June 2017): 31–36, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5467129/.

The initial impact of IPHS affected survivors’ decision-making processes and how they coped with trauma. Families whose loved ones died by IPHS immediately stepped into caretaker roles for surviving children and family members, while navigating news reporters as well as the criminal justice system to ensure justice. Some survivors became immobilized by grief and trauma. A survivor whose daughter died by IPHS discussed the initial impact:

“The dress I was wearing on the day she was taken—I didn’t bathe. I didn’t do anything for probably three weeks—I slept in it. . . . I was doped up. . . . I didn’t sleep. I didn’t eat. I don’t know where my head was at.”

Survivors in the focus groups described similar responses in the incident’s initial aftermath: shock, disbelief, and an inability to go to work or school or to tend to necessary functions like eating, sleeping, and other daily activities. Additionally, survivors themselves experienced suicidal ideation and attempts. A survivor whose daughter died by domestic violence with a firearm reported,

“All three of us attempted suicide. My youngest daughters were 14 and 15 at the time when their sister’s life was taken, and her [youngest daughter’s] [suicide] attempt was first. . . . I was trying to keep it together, and I couldn’t keep it together any longer. . . . Then I attempted and failed . . . and then I was hospitalized. . . . My daughter and I were one floor away from each other at the same hospital. It was a horrible time.”

The impact of the incident, with the compounding trauma from homicide and suicide, rippled through this family as they struggled to cope. Few studies have explored the effects of gun violence exposure on suicidal behavior. However, limited research shows that exposure to gun violence is associated with lifetime suicidal behaviors and thoughts.43Daniel Semenza et al., “Gun Violence Exposure and Suicide among Black Adults,” JAMA Network Open 7, no. 2 (2024). For the prevention of suicidality and suicide risk, we need to understand how exposure to traumatic events—especially when there are multiple deaths and traumas from one incident—serves as a risk factor.

Children as IPHS Witnesses and Victims

The impact of IPHS-related trauma can manifest differently across different life stages. During early childhood, exposure to domestic violence incidents can lead to delays in social and emotional skill development in addition to early trauma.44Jack Shonkoff et al., “The Lifelong Effects of Early Childhood Adversity and Toxic Stress,” Pediatrics 129, no. 1 (2012), https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-2663. Moreover, direct and indirect exposure to firearm violence among children and adolescents can lead to posttraumatic symptoms and acute stress and affect the emotional well-being of young people throughout their lives.45Heather Turner et al., “Gun Violence Exposure and Posttraumatic Symptoms among Children and Youth,” Journal of Traumatic Stress 32, no. 6 (2019): 881–89. In the focus group, children were witnesses in 43 percent of the IPHS incidents and were killed in 16 percent of these incidents. Other children had witnessed long-term abuse and were directly impacted by the deaths of mother, father, siblings, and others. A survivor of an attempted homicide-suicide describes the impact the incident had on her children:

“All four of the kids have had to be in therapy. We’re going on 10 years this October, and I know my oldest, because she actually wasn’t there, she feels really guilty. . . . So my oldest really struggles with a lot of depression. She still struggles with self-harm. She also self-medicates heavily and it’s caused some more serious health concerns in the past year. . . . My youngest son was 10 at the time and he got into EMDR46According to the American Psychological Association, Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) is “a structured therapy that encourages the patient to briefly focus on the trauma memory while simultaneously experiencing bilateral stimulation (typically eye movements), which is associated with a reduction in the vividness and emotion associated with the trauma memories.” It is commonly used to treat PTSD related to past domestic violence. American Psychological Association, “Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) Therapy,” 2017, https://www.apa.org/ptsd-guideline/treatments/eye-movement-reprocessing; Kristin M. Phillips et al., “EMDR Treatment of Past Domestic Violence: A Clinical Vignette,” Journal of EMDR Practice and Research 3, no. 3 (2009): 192–97, https://doi.org/10.1891/1933-3196.3.3.192. therapy for about a year and has done fantastic since then. So I mean we have a full range on the spectrum of how we’ve all done.”

These traumatic impacts on children were shared throughout the focus groups. Survivors reported that children experienced anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation, behavioral challenges, self-harm, academic challenges, school avoidance, and substance misuse. Family members also described feelings of isolation among children in schools as their peers did not interact with them. Therapy and social and familial support played critical roles in healing for child survivors as they coped with these tragedies.

Support Services and Interventions

Focus group participants noted that, prior to the homicide-suicide, victims, survivors, and perpetrators sought many types of interventions and support services. These ranged from telling family and friends about the abuse and seeking therapy to legal interventions. Participants spoke about the lack of adequate action and support from service providers and the legal system, despite the many actors involved that are intended to guard the safety of the victim and their children.

Survivors and family members who sought counseling described a lack of trauma-informed care. Survivors also pointed out the frequent inability of service providers to identify factors that put individuals at a higher risk for suicide, such as being a veteran or having previous suicide attempts. A survivor whose family members died by family annihilation homicide-suicide discussed suicidal ideation and direct threats the perpetrator had told his psychiatrist about prior to the incident:

“Now I know that he had gone into the VA hospital in Oregon because he was suicidal. . . . He was a Vietnam War vet and he had some real problems because of that. But he had threatened and told the psychiatrist he was seeing that if he got out, when he got out, he was going to start looking for me. He was going to shoot and kill me.”

Healthcare providers have the opportunity to put time and space between a person contemplating suicide and access to lethal means. Roughly two in three Americans who attempt suicide visit a healthcare professional in the month before an attempt.47Brian K. Ahmedani et al., “Racial/Ethnic Differences in Health Care Visits Made before Suicide Attempt across the United States,” Medical Care 53, no. 5 (May 2015): 430–35, https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0000000000000335. Mental health providers should be educated on the prevalence of suicides in their communities and those at higher risk for suicides.

Focus group participants also discussed the difficulty—as survivors of intimate partner violence with a firearm—in accessing support services such as mental health services. Stereotypes about survivors or victims of IPV can play a role in defining the “ideal” victim. A survivor whose daughter was killed discussed this:

“Unfortunately, there’s a lot of judgment. You have to be a perfect victim of domestic violence, just like you have to be a perfect gun violence survivor in order for people to really be interested and want to give support. People tend to shy away from complicated stories or stories where the person who was shot may not have been the perfect victim.”

The term “perfect victim” reflects decades of research showing that the victim of domestic violence most likely to receive support is weak, white, middle-class, and in a heterosexual relationship.48Nils Christie, “The Ideal Victim,” in From Crime Policy to Victim Policy: Reorienting the Justice System, ed. Ezzat A. Fattah (London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 1986), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-08305-3_2, 17–30. IPV survivors, particularly people of color, often fear they will not receive support if they seek help.49Nicole M. Overstreet and Diane M. Quinn, “The Intimate Partner Violence Stigmatization Model and Barriers to Help-Seeking,” Basic and Applied Social Psychology 35, no. 1 (January 1, 2013): 109–22, https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2012.746599. Focus group participants stated that when they did seek help, it was challenging to obtain mental health services that were culturally responsive and find providers who were aware of their community’s experience with gun violence. A survivor who was shot by their partner stated,

“I’m a BIPOC woman, Black, white, Native. . . . I tried looking for culturally diverse therapy. That didn’t work out, because even though the person [the therapist] was of color, they didn’t really understand gun violence.”

Such challenges resonated with focus group participants as they sought identity-responsive therapy. This survivor’s multiracial identity was central to her experience as a gun violence survivor. As a result, peer support networks and joining the gun violence prevention movement became central to her healing and posttraumatic growth.

Policy Matters: The Impact of Strong Versus Weak State Gun Safety Laws

Each year, Everytown releases updated state Gun Law Rankings, an online tool that ranks all 50 states based on the strength of their gun laws and catalogs 50 gun safety laws by state. Everytown Research’s analysis shows that states with strong gun safety policies, such as background checks on all gun sales and Extreme Risk laws, also known as Red Flag laws, see lower rates of gun violence. Meanwhile, states with weaker gun laws, like permitless carry and Shoot First laws, see higher rates of gun violence.

Using this ranking system, we are also able to focus in particular on the effects of laws enacted to protect women in domestic abuse situations. How do these six state-level domestic violence-related gun laws relate to intimate partner homicide-suicide?

- Emergency Domestic Violence Restraining Order Prohibitor

- Extreme Risk Law

- Firearm Possession Prohibition for Convicted Domestic Abusers

- Firearm Relinquishment for Convicted Domestic Abusers

- Firearm Possession Prohibition for Domestic Abusers Under Restraining Orders (DVROs)

- Firearm Relinquishment for Domestic Abusers Under Restraining Orders

Strong gun safety laws can prevent IPHS, according to our analysis, and even mitigate many of the risk factors identified above. Our findings show that the enactment of state laws that prevent firearm access by domestic abusers is associated with fewer intimate partner homicide-suicide deaths. The rate of IPHS with a firearm was three times higher in states with the weakest gun safety laws50 Everytown Research analysis of NVDRS data, 2014-2020. Everytown’s Gun Law Rankings are updated annually. In its 2024 rankings, used in this analysis, states with the weakest gun safety laws, which are categorized as national failures, are Alaska, Wyoming, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Kansas, Georgia, Montana, Missouri, Arizona, Kentucky, New Hampshire, Idaho, Mississippi, and South Dakota. than in those with strongest laws.51Everytown Research analysis of NVDRS data, 2014-2020. Everytown’s Gun Law Rankings are updated annually. In its 2024 rankings, used in this analysis, states with the strongest gun safety laws, which are categorized as national leaders, are Maryland, Hawaii, Illinois, Connecticut, New Jersey, Massachusetts, New York, California, and Washington. Even though California is a national leader in gun safety policies, it was excluded from this analysis because the denominator for the rates for this state represent only the populations of the counties from which the data were collected. And when we compared individual domestic violence–related firearm policies in states with weak policy against those with strong policy, we found that IPHS rates were roughly 50 to 80 percent higher in states with weak protections for survivors than in states with strong protections.52 Everytown Research analysis of NVDRS data, 2014-2020. Everytown’s Gun Law Rankings are updated annually. The 2024 Gun Law Rankings is used for this analysis, though California, Texas, and Florida are excluded because the denominators for the rates for these states represent only the populations of the counties from which the data were collected during the period of this study. For each policy, a state’s policy is considered “weak” if it did not have the relevant policy in place. For Extreme Risk Laws, a state’s policy is considered “strong” if it allows family members, in addition to law enforcement, to petition for an extreme risk protection order. For Prohibition for Convicted Abusers and Prohibition for Abusers under ROs, a state is considered “strong” if it prohibits abusive dating partners, in addition to spouses, from having firearms. For Emergency Restraining Order Prohibitor, Relinquishment for Convicted Abusers, and Relinquishment for Abusers under ROs, a state’s policy is considered “strong” if it had any version of the policy in place.

Survivors and their family members in the focus groups sought protections from gun safety laws to disarm abusers and protect their families. However, they were met with various challenges, such as stigmatization from law enforcement and the courts. Laws intending to keep guns away from abusive partners do not implement themselves, and failure to enforce them can have devastating consequences for survivors of domestic violence. The moment a survivor seeks legal assistance is often a time of heightened risk,53 Julia Bradshaw, Ellen R. Gutowski, and Kashoro Nyenyezi, “Intimate Partner Violence Survivors’ Perspectives on Coping With Family Court Processes,” Violence against Women 30, no. 1 (2024): 101–125, https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10666492/. making it even more crucial that laws to disarm domestic abusers are effectively implemented. Additional information on the implementation of these laws can be found here.

States with strong gun safety laws experienced lower rates of intimate partner homicide-suicides.

Recommendations

There are several ways to help prevent future dual tragedies of intimate partner homicide-suicide. The following recommendations for action can create opportunities for awareness, intervention, and prevention.

- Educate stakeholders on the 11 risk factors for intimate partner homicide-suicide: Throughout the focus groups, 11 common risk factors emerged that showed the victim(s) and perpetrator of the homicide-suicide were in danger. Survivors and perpetrators navigate complex systems for intervention and support, including victim services, substance misuse services, law enforcement, and the court systems. Professionals in those systems must understand the elevated risk of homicide-suicide. For example, survivor advisory councils at the local, state, and federal levels create opportunities for the people most impacted to educate diverse stakeholders.

- Create time and space between a person experiencing a crisis and their firearm, which can prevent a moment of despair from becoming an irreversible tragedy. Policies and practices including secure firearm storage in the home, giving the keys or combination to the storage device to a trusted friend or family member, or storing guns outside of the home during a period of crisis can help mitigate the risks of firearm suicide or other tragic actions.

- Intervene through DVROs and ERPOs. The focus groups offered a landscape of risk and warning signs relevant to DVROs and ERPOs. DVROs, which under federal law prohibit abusers subject to the order from having guns, may include several other vital protections for survivors and children, including ordering the abuser to stay away from the survivor, housing protections, and child custody provisions. ERPOs are solely focused on blocking a person’s access to firearms when they pose a serious threat to themselves or others. Understanding the differences between these types of orders and the circumstances in which one or both types of orders might be appropriate is critical. Law enforcement and service providers should receive training and educational materials about both types of orders to most effectively support survivors.

- Screen for suicide-related behaviors of respondents in DVRO petitions. Jurisdictions should consider including questions about suicide-related behaviors of the respondent on a DVRO petition in light of the significant link between intimate partner violence, suicidal threats, and access to a gun. Most states do not currently capture information regarding suicide-related behaviors as part of the petition process. Suicide prevention and intervention resources should be shared with any respondent who demonstrates suicide-related behaviors.

- Educate professionals in healthcare settings, law enforcement, and court systems on the co-occurrence of suicidality and IPV. Screening women for intimate partner violence in healthcare settings has been pivotal in helping to prevent this public health problem. However, IPV prevention should extend to identifying those who are at risk for suicide and who carry out violence in their relationships as well. Many suspects of IPHS had previous interactions with law enforcement and court systems, and these interactions can serve as an opportunity for intervention before a tragedy occurs.

- Disarm abusers once they are prohibited and ensure effective implementation of laws that disarm domestic abusers. For many survivors, it takes enormous courage to seek help and interventions. When they do, they are often faced with myriad challenges, including lack of enforcement of gun safety laws. Law enforcement must safely disarm the abuser once they become prohibited from possessing firearms due to a disqualifying conviction or restraining order, and our systems must ensure that abusers are not able to purchase additional firearms. The recent Supreme Court ruling in United States v. Rahimi54Everytown for Gun Safety, “United States v. Rahimi,” https://www.everytown.org/rahimi-scotus/.—upholding the constitutionality of the federal law prohibiting abusers subject to DVROs from possessing guns—provides a renewed call to action. States and local jurisdictions need to ensure that laws prohibiting domestic abusers from having guns and requiring prohibited abusers to turn in their guns are well implemented so that they can have their intended lifesaving impacts.

Conclusion

Intimate partner homicide-suicides are devastating tragedies that impact thousands of families in the United States, and firearms play a significant role in these incidents. Everytown’s focus groups showed how victims, survivors, and perpetrators navigated many layers of risk factors and protective factors leading up to these tragedies. These tragedies are preventable: risk factors such as a history of mental health challenges, substance misuse, and perpetrators’ recent police and system contact provide opportunities for intervention. But far too many abusers retain their access to a firearm—a weapon that makes it five times more likely that an abuser will kill their female partner.55Campbell, J. C. et al. “Risk factors for femicide in abusive relationships: results from a multisite case control study”. American Journal of Public Health. (2003). https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.93.7.1089.

The evidence is clear: states with laws that keep guns out of the hands of abusers saw lower rates of homicide and subsequent suicide among intimate partners. Across the nation, legislators have a duty to pass comprehensive gun safety laws, and state and local courts as well as law enforcement must properly implement existing laws to prevent the deadliest outcome of IPV, and save lives. This report is dedicated to every life taken or forever changed by an act of intimate partner homicide-suicide.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund would like to gratefully acknowledge the Ford Foundation for a generous grant that made the focus groups possible.

Help is Available

Domestic Violence Hotline

The National Domestic Violence Hotline provides free confidential support to people experiencing domestic violence and their loved ones anywhere in the US. Call 1-800-799-SAFE (7233), text “START” to 88788, or chat online at thehotline.org. You can also find more resources on domestic violence legal assistance in English and Spanish at WomensLaw.org.

988

Everytown Research & Policy is a program of Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, an independent, non-partisan organization dedicated to understanding and reducing gun violence. Everytown Research & Policy works to do so by conducting methodologically rigorous research, supporting evidence-based policies, and communicating this knowledge to the American public.