Domestic Abuse Protective Orders and Firearm Access in Rhode Island

Preface

Original research by Everytown for Gun Safety shows that people subject to final domestic abuse protective orders in Rhode Island are rarely required to turn in their guns, even when they are prohibited from firearm possession by federal law and there is evidence they have access to guns and pose a serious risk to their victims.

Executive Summary

- Firearms are frequently a factor in Rhode Island domestic abuse cases. Nearly 1 in 4 of the final orders were precipitated by petitions that contained evidence showing a firearm was present or that the abuser threatened to use one against the victim.

- Many complaints indicated a heightened risk of homicide. Almost 40 percent of final domestic abuse protective orders were precipitated by complaints that described abusive behavior matching at least one “lethality risk factor”— criteria that epidemiologists have consistently linked to domestic violence homicides.4Jill Messing and Jonel Thaller, “Intimate Partner Violence Risk Assessment: A Primer for Social Workers,” British Journal of Social Work (2014) 1–17.

- Courts rarely ordered abusers who were subject to final protective orders to turn in their firearms. Among more than 1,600 reviewed final protective orders, courts required abusers to turn in their guns in just five percent of cases (84 in total). Even when the written records indicated a firearm threat, courts ordered abusers to turn in their guns in less than 13 percent of cases; as a result, 325 abusers who appeared to have access to firearms were not ordered to turn them in.

- Even abusers prohibited by federal law were rarely ordered to turn in their firearms. Based on an analysis of the relationship between the abuser and the victim, 72 percent of final protective orders prohibited the abuser from buying or possessing firearms under federal law. Yet courts were no more likely to order abusers who were prohibited by federal law to turn in firearms than abusers who were not.5Federal law prohibits domestic abusers subject to final protective orders from possessing firearms only when the abuser and victim are “intimate partners”-current or former spouses, parents of a child in common, or current or former cohabitants–or when the victim is the child of the abuser or of the abuser’s intimate partner. Federal law does not prohibit domestic abusers subject to final protective orders from possessing firearms when the victim is the abuser’s non-cohabiting dating partner, sibling, parent, grandparent, or roommate.

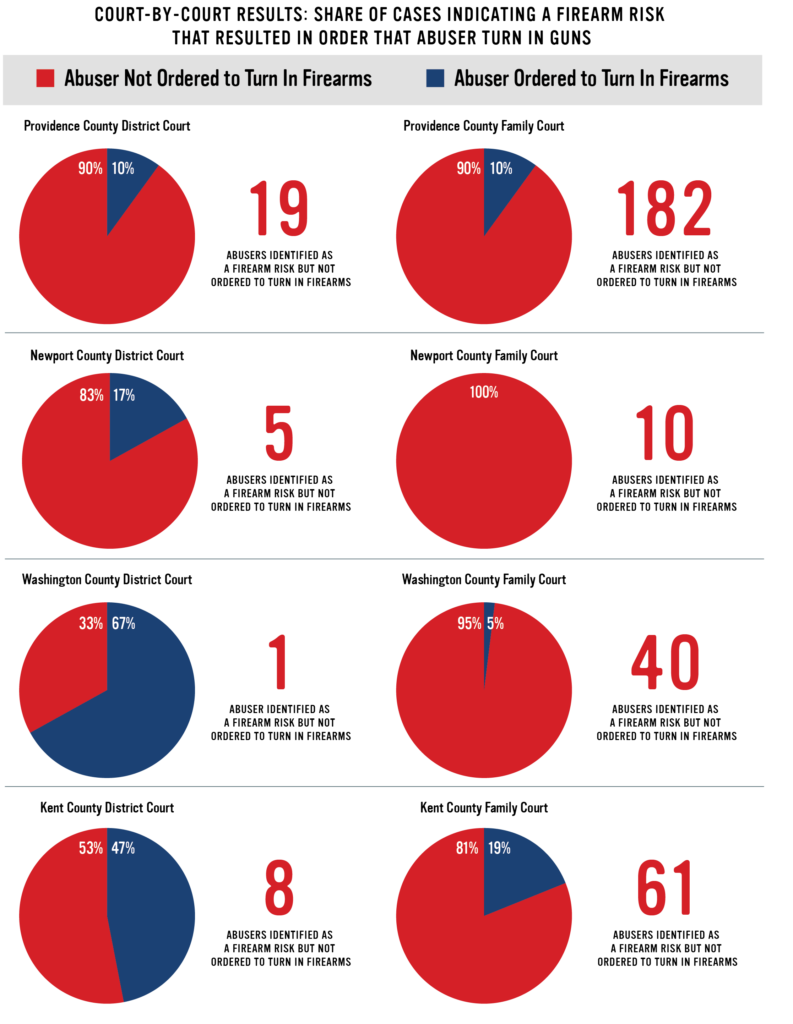

- The rate at which courts ordered abusers to turn in their guns varied substantially across the state’s court systems, from a low of 2 percent (Washington County Family Court) to a high of 53 percent (Washington County District Court).

Background: Limiting Abusers’ Access To Firearms

Domestic abuse affects the lives of thousands of Rhode Islanders. According to the Rhode Island Judiciary Administration, police responded to nearly 8,000 domestic abuse calls and made over 5,500 domestic abuse-related arrests in 2012, the most recent year for which data is available.1Rhode Island Judiciary, “Domestic Violence and Training Unit Statistics,” available at: http://1.usa.gov/1S9Ta6f. And hundreds of victims of abuse in Rhode Island also apply for protective orders through the state’s court system.

Firearms play a particularly insidious role in domestic abuse. One study in California found that about two-thirds of victims of abuse in houses with guns reported that their partners had used the weapons against them, most often by threatening to shoot or kill them.2Susan B. Sorenson and Douglas J. Wiebe, “Weapons in the Lives of Battered Women,” 94 Am. J. Pub. Health 1412-1413 (2004). Additionally, guns make it more likely that domestic abuse will turn into murder: When a gun is present in a domestic violence situation, it increases fivefold the risk of homicide for women.3J.C. Campbell, S.W. Webster, J.Koziol-McLain, et al., “Risk factors for femicide within physically abuse intimate relationships: results from a multi-state case control study,” 93 Amer. J. of Public Health 1089-97 (2003). Between 2008-12, 28 percent of Rhode Island women killed by intimate partners were shot to death, according to an Everytown analysis of FBI data.4Everytown analysis of FBI Supplementary Homicide Reports, 2008-12, available at: http://bit.ly/1yVxm4K.

A final protective order is a critical tool for shielding domestic abuse victims from further violence, in part because it can require the abuser to turn in his or her firearms for the duration of the order. Federal law prohibits intimate partners subject to final protective orders from buying or possessing guns, and 15 states — including Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and New York — require that people subject to final domestic abuse protective orders turn in their guns for the length of the order.

Domestic Abuse Protective Orders in Rhode Island

In Rhode Island, a victim of domestic abuse can seek a protective order by filing a complaint with a clerk in either Family Court or District Court.5Petitioners suffering from domestic abuse at the hands of a cohabitant or dating partner seek relief in District court. R.I. Gen. Laws § 8-8.1-1(5). Petitioners suffering domestic abuse at the hands of a present or former family member seek relief in Family court. R.I. Gen. Laws § 15-15-1(2). The person alleging abuse (the “petitioner”) identifies the person accused of abuse (the “respondent”), defines the nature of their relationship, and describes the abuse, including whether the respondent has threatened or harmed the petitioner with a weapon. The complaint prompts the petitioner to seek specific types of relief, including a request that the respondent turn in all their firearms to local police.

Once the complaint is filed, a judge determines whether the petitioner faces an immediate threat of harm.6R.I. Gen. Laws §§ 8-8.1-4(a)(2); 15-15-4(a)(2) If so, the court may immediately issue a temporary protective order—effective for up to 21 days—and schedule a hearing.7R.I. Gen. Laws §§ 8-8.1-4; 15-15-4. The court then issues a summons notifying the respondent of the temporary order and the upcoming hearing.

At the hearing, the petitioner and respondent each may testify, present evidence, and call witnesses. Both may be represented by counsel. If the evidence establishes that the respondent has subjected the petitioner to domestic abuse,8Rhode Island code does not specify a burden of proof applicable in domestic abuse protective order proceedings. The Rhode Island Supreme Court has indicated that issuance of a protective order is proper when “a fair preponderance of the evidence” establishes that the respondent has committed domestic violence upon the petitioner. Thibaudeau v. Thibaudeau, 947 A.2d 243, 247 (R.I. 2008). the court may issue a protective order barring the respondent from contacting, assaulting, molesting, or interfering with the petitioner for up to three years. The order may also instruct the respondent to immediately vacate a shared household, and a Family Court protective order may award the petitioner custody of minor children or child support payments.9Federal law prohibits people subject to final domestic abuse protective orders from possessing guns only when the abuser and victim are “intimate partners”-current or former spouses, parents of a child in common, or current or former cohabitants–or when the victim is the child of the abuser or of the abuser’s intimate partner. 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(8), 18 U.S.C. § 921(a)(32).

When a judge issues a protective order after a hearing (i.e., a final order), the respondent in that order is automatically prohibited by federal law from buying or possessing guns for the length of the order, provided the petitioner and respondent are intimate partners as defined by federal law.10Federal law prohibits people subject to final protective orders from possessing guns if the victim is the person’s current or former spouse, or cohabitates or has cohabitated with the person. 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(8), 18 U.S.C. § 921(a)(32). Federal law does not provide a mechanism to ensure that prohibited abusers turn in the guns they already own. Current Rhode Island law allows a court to order the abuser to turn in all firearms in his possession, care, custody, or control — but does not require the court to do so.11R.I. Gen. Laws §§ 8-8.1-3(a)(4); 15-15-3(a)(5).

Research Methods

The Rhode Island Administrative Office of State Courts (Administrative Office of State Courts) is responsible for maintaining state protective order data, but it does not track judicial mandates to turn in firearms in protective order proceedings. To better understand when and how courts order abusers to turn in guns in their possession, Everytown requested from the Administrative Office of State Courts every protective order filed in Rhode Island Family and District courts in 2012, 2013, and 2014. The Administrative Office of State Courts identified 2,269 case files, of which the state’s Family and District courts were able to locate 1,857 (82 percent).12The other files had reportedly been moved to an off-site archive facility, been sealed by judicial order, gone missing, or were otherwise unavailable. Occasionally, different case file numbers represented duplicate files of the same case. Everytown reviewed but ultimately excluded two additional files because the judge did not sign the final order, and one file because a copying error made the final order illegible. The Administrative Office of State Courts confirmed in writing that these case files represented every protective order in their internal database system. A physical copy was made of each of these files,13In each Family Court, as well as Newport and Washington District Court, Everytown was allowed to make the copies of the files themselves. For Kent and Providence District Court, office policies required court staff to make the copies for Everytown. and identifying information about the victim and his or her minor children was redacted at the courthouses. Everytown excluded from its analysis files that did not result in final protective orders, resulting in a final dataset of 1,609 case files.

Everytown then analyzed the data in each file to determine whether there were indications a gun was present; whether there were indications of a lethality risk factor; whether the order prohibited the abuser from buying or possessing firearms under federal law; and, finally, whether the court ordered the abuser to turn in his or her firearms. To conduct this analysis, Everytown examined all available documents the court would have viewed when deciding whether to order an abuser to turn in his firearms, including the victim’s Complaint, the victim’s Written Statement, and the Judgment (the final protective order).

Analyzing handwritten records always presents challenges. To assess whether errors made during manual review of the records or data-entry could have affected the analysis, Everytown randomly selected 5 percent of the case files, repeated the classification, and compared the results to those already recorded in the main dataset. Errors in the main dataset were negligible (ranging from 0 to 3 percent) and random, so would not be expected to bias the results.

The Evidence Reviewed for a Protective Order Issued by Providence Family Court in 2013

Document 1: Complaint

First, Everytown examined each complaint for information on the relief the petitioner was seeking and the relationship between the petitioner and the respondent.

In this example, the petitioner checked boxes indicating that she and the respondent had children in common, asking the court to restrain the respondent from further abuse, and asking the court to order the respondent to turn in his firearms to the local police department. Below, the checked box indicates that the petitioner requested that respondent turn in his firearms to the local police department.

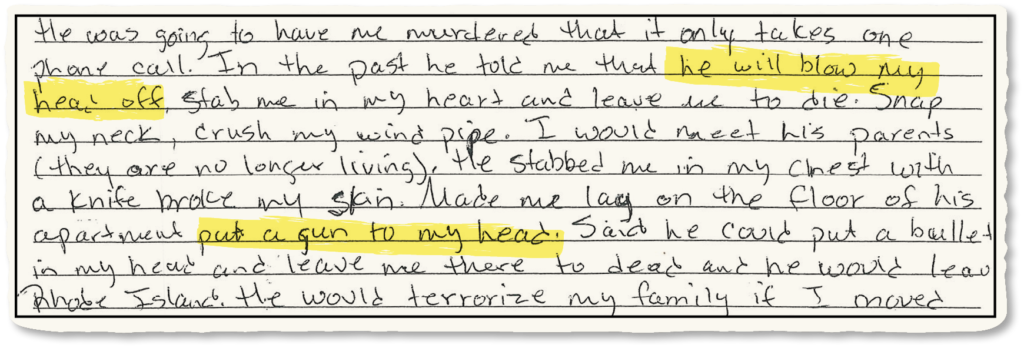

Document 2: Written Statement

Everytown then analyzed the petitioner’s written statement to look for evidence that the respondent possessed or had threatened the petitioner with a firearm, and to determine whether the respondent had exhibited behaviors matching any lethality risk factors.

Below, the petitioner wrote that the respondent had threatened to “blow [her] head off,” and had forced her to “lay on the floor of his apartment [and] put a gun to [her] head.”

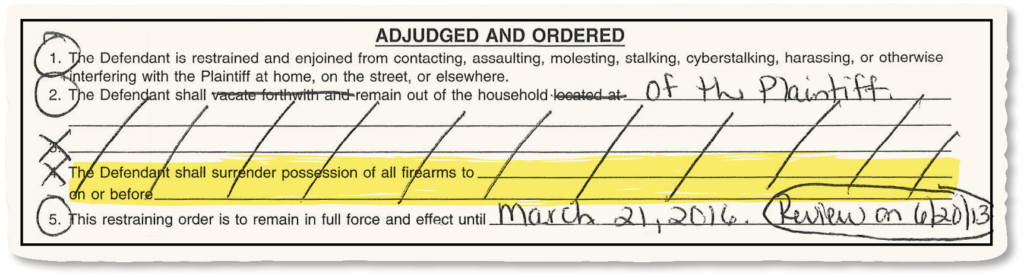

Document 3: Protective Order

Finally, Everytown reviewed each judgment to assess whether the respondent had been ordered to turn in firearms.

Below, the judge circled numbers 1 and 2 to order the respondent to refrain from contacting, assaulting, molesting, stalking, cyberstalking, harassing, or otherwise interfering with the petitioner, and to stay out of the petitioner’s household. The judge crossed out number 4 to clearly indicate that he or she would not order the respondent to turn in his firearms.

Results

Everytown’s analysis of Rhode Island final protective orders suggests that domestic abusers who are subject to final protective orders in the state and prohibited from possessing guns under federal law are rarely required to turn in their firearms.

| District Court | Total Final Protective Orders | Ordered to Turn in Firearms | Included Evidence of a Firearm | Ordered to Turn in Firearms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Providence County* | 108 | 5 | 21 | 2 |

| Newport County | 12 | 1 | 6 | 1 |

| Washington County | 17 | 9 | 3 | 2 |

| Kent County | 47 | 19 | 15 | 7 |

| Family Court | Total Final Protective Orders | Ordered to Turn in Firearms | Included Evidence of a Firearm | Ordered to Turn in Firearms |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Providence County* | 1022 | 31 | 202 | 20 |

| Newport County | 68 | 2 | 10 | 0 |

| Washington County | 94 | 2 | 42 | 2 |

| Kent County | 241 | 15 | 75 | 14 |

*Courts in Providence County also hear domestic abuse protective order proceedings originating in Bristol County.

Firearms are frequently a factor in Rhode Island domestic abuse cases. Nearly 1 in 4 final orders were precipitated by a complaint that indicated a firearm risk: explicitly mentioning the presence of a firearm, describing how the abuser had threatened to use a gun against the victim, or specifically requesting that the court order the abuser to turn in his firearms.14This measurement may undercount the number of cases where a victim indicates to the court that an abuser threatened her with a firearm. The Family Court complaint forms offered the victim a formal opportunity to mark a box indicating that the abuser had threatened her with a weapon and asked her to specify which kind of weapon, but the District Court complaint forms did not contain a similar opportunity for victims to make a formal note of a weapons threat.

Almost 40 percent of victims’ requests for protective orders included strong indicators that their abusers posed a lethal danger. In 633 cases, victims described abusive behavior matching at least one “lethality risk factor” — a set of criteria that epidemiologists have consistently linked to homicide — including threats to kill, strangulation, recent separation from their partners, or the presence of a firearm in the home. Yet of these cases where there was evidence that the abuser posed a lethal danger, courts ordered them to turn in their guns in only 61 cases (10 percent).

Courts in Rhode Island rarely order abusers who are subject to final protective orders to turn in their firearms. Of the 1,609 final protective orders reviewed, courts required just five percent of abusers to turn in their guns (84 cases). Even in cases where written records provided evidence of a firearm threat, courts ordered the abusers to turn in their guns just 13 percent of the time. Three hundred twenty-five abusers who appeared to have access to firearms were not ordered to turn them in.

Even abusers prohibited by federal law were rarely ordered to turn in their firearms. Based on an analysis of the relationships between abusers and victims, 72 percent of final protective orders prohibited the abuser from possessing firearms under federal law. But courts were no more likely to order abusers who were prohibited by federal law to turn in firearms than abusers who were not: only 5.2 percent of each group were ordered to turn in firearms. Further, while abusers in Family Court were almost twice as likely to qualify for federal prohibition as abusers in District Court, Family courts–which issued 89 percent of all final domestic abuse protective orders–were far less likely than District courts to order federally-prohibited abusers to turn in their firearms.

The rate at which courts ordered abusers to turn in their guns varied substantially across counties. Whereas six courts ordered abusers to turn in their firearms less than 9 percent of the time overall, two courts ordered abusers to turn in their guns at significantly higher rates: Washington County District Court (53 percent) and Kent County District Court (40 percent). These courts appeared particularly attuned to ordering abusers to turn in their guns when a victim’s file mentioned a firearm. In such cases, Washington County District Court ordered abusers to turn in their firearms 67 percent of the time and Kent County District Court ordered abusers to turn in their firearms 47 percent of the time.

Cases

The firearm threats described in the case files were often stark, yet in most cases they did not result in orders requiring abusers to turn in their guns:

- In 2013, a woman from Chepachet filed a request for a protective order in Providence Family Court against her 44-year-old former boyfriend. In her written statement, the woman described “aggressive and harassing” behavior and noted that “he owns a gun and I’m afraid he will show up at my new house and kill me and the children…one time he took the gun to his head and threatened to kill himself.” The woman requested that the court order her former boyfriend to turn in his firearms. Although the court issued a protective order, it did not order the former boyfriend to turn in his firearms.

- In 2012, a woman from Providence filed a request for a protective order in Providence Family Court against her 28-year-old estranged husband. In her written statement, the woman described how he broke into her new home that she shares with their young children, and, after threatening her life, “told me that he was going back to his truck to get a gun to kill me.” The woman requested that the court order her estranged husband to turn in his firearms. Although the court issued a protective order, which prohibited the estranged husband from possessing firearms under federal law, it did not order him to turn in his firearms.

- In 2013, a woman from Providence filed a request for a protective order in Providence Family Court against her 50-year-old former boyfriend and the father of her two young daughters. In her written statement, the woman wrote that during an argument, the former boyfriend “made me lay on the floor of his apartment and put a gun to my head. Said he could put a bullet in my head and leave me there…” The woman requested that the court order her former boyfriend to turn in his firearms. The court issued a protective order, which prohibited the former boyfriend from possessing firearms under federal law, but it did not order him to turn in his firearms.

- In 2013, a woman from North Kingston filed a request for a protective order in Washington Family Court against her 27-year-old estranged husband. In her written statement, the woman described how her husband “had their children and refused to give them back. He called me later that night and threatened to come to my house and shot [sic] me.” The woman requested that the court order her estranged husband to turn in his firearms. Although the court issued a protective order, which prohibited the estranged husband from possessing firearms under federal law, it did not order him to turn in his firearms.

Although they only did so in a minority of cases, courts can and did order some abusers to turn in their firearms:

- In 2012, a woman filed a request for a protective order in Providence Family Court against a man she had previously dated and with whom she had a child. In her written statement, she described an argument in which the man told her he was going to “get his gun” and that “she was going to get it,” and she requested that the court order him to turn in his guns. When it issued the protective order, prohibiting the man from possessing firearms under federal law, the court also instructed the man to turn in his guns to the local police department.

Recommendations

This analysis of court data suggests that existing Rhode Island law does not sufficiently protect domestic abuse victims from the threat of armed abusers. Rhode Island courts rarely require abusers to turn in their firearms, even when they are under protective orders that prohibit them from possessing firearms under federal law and there is evidence that they have access to guns and pose a lethal risk to victims.

Fifteen states have closed this loophole by creating a procedure for courts to follow that requires all abusers subject to final domestic abuse protective orders to turn in their guns for the length of their orders. States that restrict access to firearms by those under domestic violence restraining orders, including by requiring them to turn in guns, see a 25 percent reduction in intimate partner gun homicides.15A Zeoli and D Webster, “Effects of domestic violence policies, alcohol taxes and police staffing levels on intimate partner homicide in large US cities,” Journal of Injury Prevention, 2010, available at http://bit.ly/1qbHZxG.

Comprehensive legislation that requires domestic abusers to turn in their firearms would keep guns out of dangerous hands and protect Rhode Island women and families. Rhode Island policymakers should bring state law in line with federal law by enacting legislation that prohibits people subject to domestic abuse protective orders and people convicted of domestic violence crimes from possessing guns. The state should further protect victims by requiring domestic abusers to turn in their firearms to law enforcement or licensed gun dealers upon becoming prohibited.

Learn More:

Everytown Research & Policy is a program of Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, an independent, non-partisan organization dedicated to understanding and reducing gun violence. Everytown Research & Policy works to do so by conducting methodologically rigorous research, supporting evidence-based policies, and communicating this knowledge to the American public.