Business As Usual

How High-Volume Gun Sellers Fuel the Criminal Market and How the President Can Stop Them

Preface

A regulation that clarifies the “engaged in the business” standard would clarify for gun sellers whether they need to get a federal firearms license — and consequently comply with all dealer regulations and conduct background checks. And it would put teeth into the federal statute that law enforcement use to prosecute gun traffickers and high-volume sellers who feed the criminal market.

Executive Summary

Selling guns doesn’t have to be a risky business.

Every day across America, tens of thousands of professional, responsible gun dealers engage in the business of selling firearms. They are licensed and subject to regular inspections, and they conduct criminal background checks on every prospective buyer to ensure he or she can lawfully possess firearms before handing a gun across the counter.

People without licenses can sell firearms, too, if they offer guns occasionally or sell exclusively from their personal collections.

But a lack of clarity in the federal definition of “engaging in the business” of selling firearms has created a hazy arena between firearm dealers who must obtain a license, and occasional sellers who need not obtain a license or conduct background checks.

Under federal law, anyone “engaged in the business” of dealing firearms must get a license and follow dealer rules, including running background checks on potential buyers. In contrast, those who make only “occasional sales…for a hobby” or who sell only from their “personal collections” need not be licensed. But the absence of a clear definition for “engaging in the business,” and for what constitutes “occasional sales” and “personal collection,” allows these distinctions to blur.

Some unlicensed sellers take advantage of this ambiguity to offer tens or hundreds of guns for sale each year, tapping into the lucrative firearms market without following the rules. They sell guns without background checks, and as this report shows, some of those guns are later trafficked across states lines, recovered at crime scenes in major cities, and used against police officers.

While these high-volume unlicensed sellers defy the intent of the law against “engaging in the business” of dealing guns without a license, they can argue that they do not defy its letter—because the vague language of current law gives them ample room to play fast and loose with public safety.

The President has the power to clarify the “engaged in the business” standard through regulation, drawing for the first time an evidence-based distinction between the few unlicensed sellers who abuse the system and the majority of gun owners who sell guns only infrequently. If he does not, some high-volume sellers will continue to evade the dealer licensing laws and sell thousands of guns into the underground market with near impunity. And law enforcement will remain unable to stop them.

To assess whether gun sellers are taking advantage of the lack of clarity in this standard, Everytown looked at how people sell guns in the U.S.—both those accused of having sold guns illegally and those operating in the country’s largest online marketplace for unlicensed gun sales.

Similar to the landmark Department of Justice report Following the Gun, which examined two years of gun trafficking investigations, Everytown analyzed every federal prosecution of “engaging in the business” of dealing guns without a license in 2011 and 2012. And because the internet has reshaped firearm commerce in the 21st century, Everytown also drew a unique dataset from the online marketplace: over half-a-million gun ads posted publicly on the website Armslist.com by unlicensed sellers. These two datasets give us a unique window into the behavior of unlicensed sellers.

We have three main findings:

First, the prosecutions show that “engaging in the business” without a license is a risky business. It is closely linked with gun trafficking across state and national borders, often involves felons and drug criminals, and relies at least in part on existing marketplaces well known for unlicensed gun sales without background checks:

– Nearly one-quarter of prosecutions involved alleged gun trafficking across state or national borders, as guns originating in states with weak laws imperiled residents in neighboring states.

– The sellers were often criminals themselves. Three in ten defendants charged with dealing guns without a license were also charged with illegal firearm possession; 17 percent were charged with drug crimes; and seven percent of the prosecutions involved stolen firearms.

– In approximately 10 percent of cases, the defendants relied on gun shows, online markets, or print ads to buy or sell their wares.

Second, our analysis shows how the current “engaging in the business” standard lacks the clarity necessary to be an effective law enforcement tool. Even a defendant selling hundreds of guns and earning tens of thousands of dollars in profit was acquitted of the charges when brought to trial.

– Prosecutors accept a lower share of “engaged in the business” cases when compared to referrals for other comparable federal crimes. Prosecutors accept these cases only 54 percent of the time compared to 77 percent for drug trafficking crimes.

– When prosecutors do bring charges, three in ten defendants charged with “engaging in the business” were not ultimately convicted of that charge. Moreover, when defendants accused of dealing guns without a license go to trial, they are acquitted of that charge nearly half (47 percent) the time, indicating that inconsistent application of the standard makes it difficult to anticipate what type of conduct qualifies as a violation.

Third, our first-of-its-kind analysis of a nationwide online gun marketplace provides evidence that a narrow group of sellers, who should have obtained a license but did not, are offering guns in extremely high volumes. We tested whether unlicensed sellers offering 25 or more guns a year—who play a disproportionate role in the unregulated market—are more likely than not to meet multiple additional factors for illegally “engaging in the business” without a license. The results showed that they were, and that they differed significantly from low-volume sellers:

– Of sellers we identified online, those offering 25 or more guns accounted for 1 in 500 sellers but offered 1 in 20 guns.

– Selling large quantities of guns is highly associated with the factors established through case law as indicators of unlawful “engaging in the business.” High-volume sellers are more likely than not to meet multiple factors of being “engaged in the business”—and are three times as likely to be characterized by multiple factors as are low-volume sellers.

Based on this evidence, we conclude that the President can reduce gun trafficking and save lives by issuing a regulation that clarifies the “engaged in the business” standard. A strong regulation would clarify and define key terms as follows:

– First, it should codify the factors that courts have used to determine if a person is unlawfully “engaged in the business” of selling firearms.

– Second, it should create an inference that a person who sells 25 or more guns during a one-year period is “engaged in the business” of selling firearms. Our research provides evidence that an inference of this type would impact a very narrow fraction of unlicensed sellers, but the majority of those above it would clearly meet criteria for “engaging in the business.” While the results show that those above the threshold are more likely than not to exhibit multiple factors for “engaging in the business,” they do not discount the possibility that sellers operating at slightly lower thresholds also meet these criteria. Therefore, this study provides a conservative bar at which a numeric standard for “engaging in the business” might be established.

– Finally, since the statute allows people to engage in “occasional sales” and to sell gun from their “personal collection” without getting a license, a regulation should define these two terms:

– The legislative history suggests that the “occasional sales” exception was intended to exempt people who were selling just a few guns. A regulatory limit on how many guns can be sold in “occasional sales” would cap the number of guns a hobbyist can sell in a year, while still allowing people to liquidate their personal collections of firearms.

– “Personal collection” should be defined to exclude guns obtained for the purpose of selling or trading. Further, as with dealer-owned firearms, a gun should not qualify for the “personal collection” exemption until it has been owned for a period of one year, unless it was obtained through inheritance.

History of a Loophole

Americans suffer from an extraordinary rate of gun violence, 20 times higher than nations with comparable levels of economic development.1EG Richardson and D. Hemenway, “Homicide, Suicide, and Unintentional Firearm Fatality: Comparing the United States with Other High-Income Countries, 2003,” Journal of Trauma 70, no. 1 (2011): accessed June 30, 2015, http://1.usa.gov/1IqE60d. To address this scourge without infringing on lawful ownership of firearms, federal law bars several narrow categories of people—including felons, domestic abusers, and people with severe mental illness—from possessing firearms on the basis that they pose an elevated risk of harm to themselves or others.

Professional gun dealers play a pivotal role in enforcing this prohibition. Given the inherently lethal nature of their wares, every dealer is required to obtain a federal firearm license by submitting an application and fingerprints to the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives (ATF), undergoing a background check, and paying a processing fee of $200.2Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives: Instructions for Form 7 – Application for Federal Firearms License, available at http://1.usa.gov/1XZORwe (last visited Oct. 11, 2015). One of a gun dealer’s most important responsibilities is to consult the national background check system before transferring a firearm to any prospective buyer, and to retain paperwork on the sale for 20 years. If the background check concludes that the prospective gun buyer is prohibited from purchasing firearms, the dealer must deny the sale and refuse to transfer the gun. Since 1998, dealers have stopped nearly 2.5 million gun sales to prohibited people, and have assisted law enforcement in attempting to trace over 5 million recovered firearms.3Bureau of Justice Statistics, U.S. Department of Justice, NCJ 247815, Background Checks for Firearm Transfers, 2012 – Statistical Tables available at http://1.usa.gov/1DaX5UW (last accessed Nov. 11, 2015);Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives: National Tracing Center Fact Sheet, available at http://1.usa.gov/1GVIkOF (last visited Nov. 10, 2015). Licensed dealers may also be inspected by the ATF on an annual basis to ensure they are complying with all relevant laws.4Among other regulations, dealers are required to keep acquisition and disposition records of their sales—which records are critical for law enforcement that recover guns at crime scenes and are seeking to establish a chain of custody and catch a criminal or break up a trafficking ring. Licensees help to enforce federal firearm laws in other critical ways, including for example by enforcing the law that bars gun buyers from crossing state lines to buy handguns and by ensuring that prohibited persons cannot use a “straw purchaser”—a third-party who is not barred from buying guns—to buy guns illegally on their behalf. See 27 C.F.R. § 478.124 (2014) These responsibilities are a cornerstone of public safety.

In contrast, federal law does not require unlicensed sellers to adopt these safeguards. Since a seller might be tempted by the economic opportunity of dealing firearms without obtaining a license—or might simply want to duck the regulations required of licensed dealers—Congress created a threshold to separate dealers from casual sellers, and made it a crime to “engage in the business” of dealing firearms without a license. But the 1968 law that established this “engaging in the business” standard did not define the term, leaving gun sellers little guidance about what level of activity would obligate them to get a license, and law enforcement without a clearly delineated crime to enforce.

The current language dates from 1986, when the Firearm Owners’ Protection Act (FOPA) first defined the term, including the exception allowing unlicensed people to make “occasional sales” and sell guns from their “personal collections.” The standard was discussed in legislative hearings at that time, and the testimony indicates that the goal of the legislation was to create a clear definition for what constitutes “engaged in the business” and to protect people who sell guns in very small numbers.

For example, Senator James McClure (R-ID), the bill’s sponsor, said that the legislation would address the problem wherein sellers were prosecuted for transferring “two, three, or four guns from their collection.”5The Firearms Owner Protection Act, Hearing Before the S. Comm. On the Judiciary, 97th Cong. 47(1981) (statement of Sen. James McClure). Likewise, Senator Orrin Hatch (R-UT) said that the new definition would protect people from selling “two or three weapons from their personal collections and thus unwittingly violating” the law.6The Federal Firearms Owner Protection Act, Hearing Before the S. Comm. on the Judiciary, 98th Cong. 5 (1983) (Statement of Senator Orrin Hatch). The head of the National Rifle Association’s Institute for Legislative Action, the organization’s lobbying branch, similarly described the problem as “prosecutions on the basis of as few as two sales.”7The Firearms Owner Protection Act, Hearing Before the S. Comm. On the Judiciary, 97th Cong. 47 (1981) (Statement of Neal Knox, Exec. Dir. NRA-ILA).

Though the clear implication of this testimony was that the updated definition was meant to generally cover most high-volume sellers and to exclude only low-volume sellers,8One congressional witness said that without a clear definition, “the standard changes, not only from one year to the next but on a case by case basis.” Statement of David T. Hardy, Senate Judiciary Committee, 1981. Senators spoke of “a vague legal definition…the end result [of which] is tremendous confusion”and “a hodgepodge of legal interpretations” Statement of Sen. James Abdnor, Statement of Sen. Orrin Hatch, June 24, 1985 Vol. 131, No. 85. And the House sponsor said that the new definition aimed to address “a complete lack of certainty.” Statement of Rep. Harold Volkmer, 131 Cong Rec H 824 February 28, 1985 A top government official speaking for the Reagan Administration said that further definition would “establish clearer standards for law enforcement officers in investigating potential violations of the law.” Robert E. Powis, 1983 Senate Judiciary Hearing at 47, 50-51 the result has been to provide a safe harbor for people selling hundreds of guns and making tens of thousands of dollars in profit.

More than a decade after the effort to clarify the law, the ATF issued a report documenting how the vague definition continued to hamper law enforcement, despite the fact that more than half of the illegal activity their investigations unearthed at gun shows involved people dealing without a license. The lack of clarity provided law enforcement and prosecutors with insufficient authority to police the border between dealers and unlicensed sellers, the Treasury argued, “frustrat[ing] the prosecution” of alleged wrongdoers, and holding up enforcement while months of undercover work and surveillance take place to prove each element of the definition.9The Department of the Treasury, the Department of Justice, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms, “Gun Shows: Brady Check and Crime Gun Traces,” January 1999, available at https://www.atf.gov/file/57506/download.

Given the unintended safe harbor the statute has created for high-volume sellers and the continued lack of clarity as to what constitutes “engaging in the business” of dealing firearms, the Administration should promulgate regulations defining key terms. To shed light on how this might be accomplished, this report draws on two datasets. First, we examine a comprehensive database of federal prosecutions of defendants who were allegedly dealing guns without a license, describe the behaviors identified in connection with these crimes, and assess law enforcement’s success at bringing alleged wrongdoers to justice. Second, we examine a first-of-its-kind dataset of more than half-a-million gun ads posted by unlicensed sellers in the country’s largest online marketplace, to better understand what share of sellers are operating at a high-volume, what share of total gun sales they account for, and if they differ in other qualitative ways from low-volume sellers.

Methods

Analysis of Federal Prosecutions

In the first phase of this investigation, Everytown examined how the current “engaging in the business” standard is enforced in practice — by looking directly at a comprehensive set of prosecutions brought by federal prosecutors against sellers allegedly dealing guns without licenses. These cases offer a vivid glimpse of how the wider underground gun market operates, and also provide some evidence about the utility of the tools currently available to law enforcement and prosecutors for securing convictions under this statute and holding black market dealers accountable.

Data

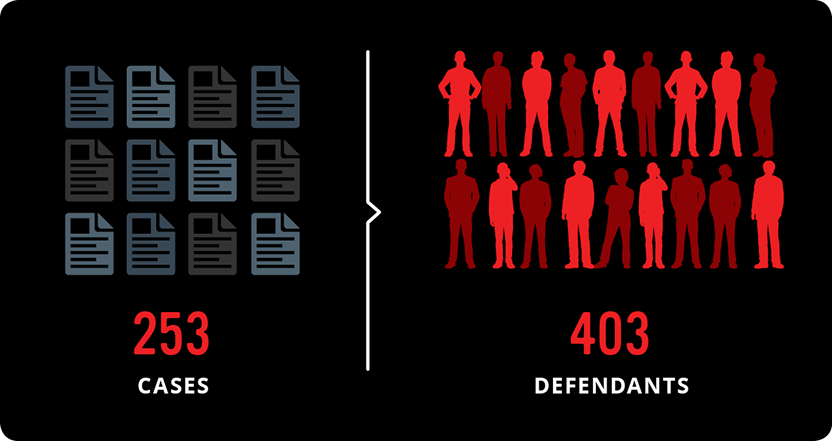

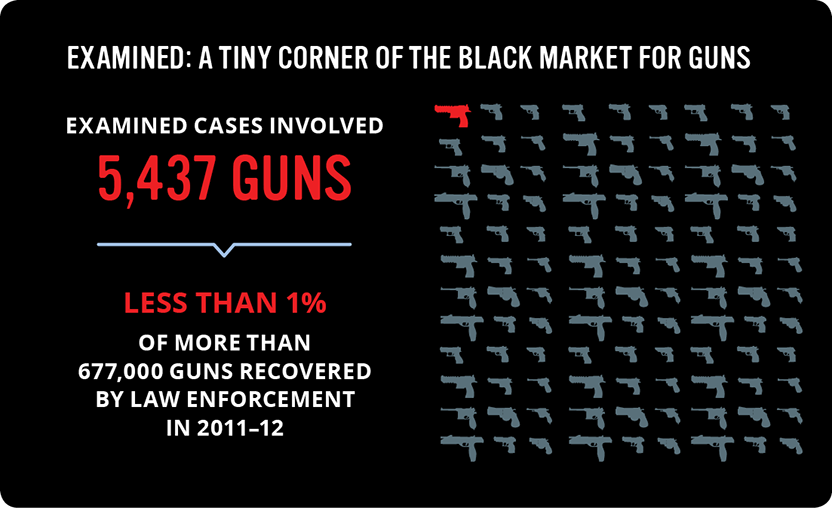

Everytown reviewed every “engaged in the business” prosecution pursuant to the law, 18 U.S.C. 922(a)(1)(A) that was filed between 2011-2012.10This includes charges for 18 USC § 922(a)(1)(A), Conspiracy (18 USC § 371) to violate 18 USC § 922(a)(1)(A), and Aiding/Abetting (18 USC § 2) the commission of a violation of 18 USC § 922(a)(1)(A). Indictments, pleas agreements, trial transcripts, and any other relevant documents were obtained from Public Access to Electronic Court Records (PACER). In all, there were 253 cases brought in 49 districts, with a total of 403 defendants.11Cases that were still pending, or that were dismissed due to the defendant’s death, were excluded. They represented just a tiny corner of the black market for guns, involving some 5,000 documented firearm sales compared to 677,000 guns recovered by law enforcement and submitted to ATF for tracing in 2011 and 2012.12Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives: National Tracing Center Fact Sheet, available at http://1.usa.gov/1GVIkOF (last visited Nov. 10, 2015).

Analysis

Everytown reviewed the available court records for each case and classified each according to a number of variables, including:

- Accompanying charges

- Disposition of the “engaging in the business” charge

- Presence of guns that were reported stolen or that had obliterated or missing serial numbers13Researchers categorized cases as having a firearm with an obliterated or missing serial number when they were described in the court documents as being “obliterated,” “removed”, “defaced”, “missing”, “having no serial number,” or if the defendant had manufactured the gun deliberately without a serial number.

- Location of purchases and sales

- Method of sales (gun shows or print or online advertising)

Court records varied greatly in their length, and they did not always include sufficient detail to make a determination about all the variables of interest, so the findings represent a conservative estimate of the prevalence of various factors. For example, the fact that the court record contains no evidence of a firearm with an obliterated or missing serial number does not rule out the possibility that such a gun was involved in the case.

Analyzing the records sometimes also required interpretation of unclear or conflicting details about the alleged behavior. To assess whether errors made during manual review of the records or data-entry could have affected our analysis, a second reviewer repeated the classification of a random sample of 20 percent of the defendants (79 prosecutions), and the results were compared to those already recorded in the main dataset. Errors in each field of data were negligible (ranging from zero to six percent) and were almost exclusively of under-inclusion, so would only lead to underestimating the prevalence of the other factors.

In order to compare the disposition of federal prosecutions for “engaging in the business” to other criminal statutes, Everytown also obtained data on federal prosecutions from the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC). Established in 1989, TRAC is a data research and distribution organization at Syracuse University that provides information on the enforcement, budgetary, and staffing activities of the federal government, which they have obtained through Freedom Of Information Act requests.14TRAC: About Us, Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, Syracuse University, http://bit.ly/1HFr8rA (last visited Oct. 29 2015). While useful, data held by TRAC are limited by the fact that prosecutions are categorized by lead charge only,15TRAC employs the following definition of lead charge: “Different data systems use different criteria for determining which of the charges to pick as the most serious or lead charge. The U.S. Courts and the U.S. Sentencing Commission use the charge with the maximum statutory penalty that can be applied; the U.S. Prisons classify by the most serious penalty in fact applied. The federal prosecutors use a more subjective rule: ‘the substantive statute which is the primary basis for the referral’ where primary is left for determination to the individual assistant U.S. attorney who is assigned the case. Note also that the classification takes place at the time the referral is received. It is thus possible that the defendant may not ultimately be prosecuted on this charge.” See TRAC: About Us, Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, Syracuse University, http://bit.ly/1HFr8rA (last visited Oct. 29 2015). and do not capture prosecutions in which “engaging in the business” was not the lead charge. Their data is also organized according to the fiscal year of the prosecutorial event,16In other words, if a case was referred in 2010 but prosecuted and resulted in a conviction in 2011, the referral would appear in 2010 data and the conviction and disposition would appear in 2011 data. The federal fiscal year is defined as October – September, e.g. 2011 would be October 2010 – September 2011. so are not directly comparable to Everytown’s analysis of cases in the 2011-12 calendar years.

Investigating Sales Practices in the Country’s Largest Online Gun Market

In the second phase of this investigation, Everytown took the measure of today’s market for unlicensed gun sales, and the role that high-volume sellers play within it.

Under current federal law, unlicensed sellers can transfer guns without requiring a background check or keeping a paper record of the transaction. These sales are most prominent when they occur in large marketplaces such as gun shows or via classified advertisements, but they may also take place informally between neighbors, coworkers, or complete strangers. The scope and shape of this unlicensed gun market is therefore indeterminate.

The advent of the internet has reshaped firearm commerce just as it has many other industries. Dozens of websites now host tens of thousands of for-sale gun ads posted by unlicensed sellers and provide a forum for strangers to connect and arrange offline gun transfers, like Craigslist does for furniture or concert tickets. These ads represent a unique dataset because they provide an electronic record of likely firearm sales. Capitalizing on this publicly available data, Everytown explored what share of unlicensed online firearm sales are attributable to high-volume sellers, and what other sales practices differentiate their commerce from that of more casual sellers.

Gun Ad Data

Each day for a one-year period, Everytown “scraped” (a software technique for collecting online data) all gun ads posted by self-described “private,” unlicensed sellers on the country’s largest online marketplace, Armslist.com.17Ads were collected from October 15, 2014 to October 14, 2015. Over the year, 709,206 ads were captured.

For any given ad on Armslist, the website allows visitors to view other “listings by user.” This enabled Everytown to link each ad with any other ads posted by the same user, along with any ads linked to them, and so on. Over time, this data mapped out the contemporaneous gun ads listed by any given seller, and the distribution of sales volume across the total population of sellers — from those who listed a single gun ad for sale to those who advertised tens or hundreds.

This technique yields a conservative estimate of sellers’ total gun listings because it only links ads together that are online simultaneously. If a seller posts an ad but removes it before posting a new one, such that they are never online at the same time, the website would never establish a link between them, and observers would mistakenly attribute the new ad to a different seller, thus undercounting the seller’s true volume of sales.

Sellers occasionally “re-post” ads to increase their visibility on the website, so Everytown took steps to remove copies of identical advertisements. Specifically, the computer program Paxata was employed to identify and remove those ads posted by the same seller that had significant patterns of matching text within the first 45 characters of the description of the items for sale.18Paxata (Fall 2015 Release) [Computer Software]. Redwood City, CA. The final, de-duplicated dataset contained 644,715 ads offering guns for sale.

After completing this procedure we manually reviewed ads posted by the ten highest-volume sellers. On average, 9 percent of ads appeared to refer to the same item as another ad, a rate that would not substantially affect the results.

Undercover Calls

Everytown then sought to assess whether the sales practices of high volume sellers vary from those of more infrequent, casual sellers — and specifically, if they are more likely to exhibit behaviors that courts have used to define the crime of “engaging in the business” without a license.

The statutory definition of “engaged in the business” sweeps broadly in that it includes sellers who make repetitive purchases and sales for profit, but it is short on explanatory detail for how to establish those elements. Over several decades, courts applying the law to defendants have developed common-law factors to fill in the gaps.19A federal circuit court has said that the “engaged in the business” inquiry is broad and lends itself to a totality of the circumstances test: A jury “must examine the intent of the actor and all circumstances surrounding the acts…[T]he importance of any of these [factorial] considerations is subject to the idiosyncratic nature of the fact pattern….” United States v Tyson, 653 F.3d 192 (3rd Cir. 2011).

To assess whether sellers met these factors, Everytown contracted with private investigators to randomly sample sellers who listed a high volume of gun ads during the year—25 or more—and a control group of casual sellers that posted fewer ads. An investigator called each seller under the pretext of shopping for a firearm, and engaged him or her in conversation using a script designed to elicit evidence of whether the seller met four factors commonly used by judges to determine if a seller is unlawfully “engaged in the business” without a license.

- Courts have used regularity of selling guns as a factor to determine whether defendants are illegally dealing firearms without a license.20One circuit court has referred to the “frequency of sales” as a key factor for meeting the “engaging in the business” standard. United States v. Brenner, 481 F. App’x 124 (5th Cir. 2012). Another circuit court found it probative to incriminate a defendant that he had admitted to buying “a lot of guns.” United States v. Beecham, 1993 U.S. App. LEXIS 13050 (4th Cir. 1993). Yet another circuit found evidence to be incriminating that a defendant had engaged in “repetitive sales” by traveling to sell firearms on four occasions over a seven-month period. United States v Tyson, 653 F.3d 192 (3rd Cir. 2011). For the purposes of the study, we classified respondents as selling guns regularly if they clearly described a uniform pattern of commerce — either claiming to sell “all the time,” “a lot,” or “regularly” — or if they had posted gun ads in at least six separate calendar months during the year-long period of observation.

- Courts have held that any indication that an unlicensed seller is making a profit may be factored into the analysis of whether they are illegally dealing firearms.21Multiple circuit courts have used selling firearms for a profit as a core indicator that a person is “engaged in the business” of selling firearms. United States v Huffman, 518 F.2d 80 (4th Cir. 1975); United States v. Pegg, 542 F. App’x 328 (5th Cir. 2013). Simply selling firearms “for more than what they were worth” can suffice as probative evidence. United States v. Beecham, 1993 U.S. App. LEXIS 13050 (4th Cir. 1993). According to one circuit, it is not necessary for this element that a person actually does turn a profit: “[A] conviction requires that the defendant had the ‘principal objective’ of making a profit, but it does not require that he succeeded in that endeavor.” United States v. Shipley, 546 F. App’x. 450 (5th Cir. 2013). Indeed, legislative history makes it clear that a seller need not sell firearms as his or her primary occupation in order to be incriminated by a profit motive,2222Engaging in the business “does not require that the sale or disposition of firearms be, or be intended as, a principal source of income or a principal business activity…this provision would not remove the necessity for licensing from part-time businesses or individuals whose principal income comes from sources other than firearms.” S. Rep. No. 98-588, at 8 (1984). and one federal court has found the amount of profit to be immaterial to establishing this factor.23United States v. Approx. 627 Firearms, 589 F. Supp. 2d 1129 (S.D. Iowa 2008). For the purposes of the study, a seller was deemed to fulfill the factor if he or she clearly described making a profit or the intention of making a profit above the purchase price on the resale of any firearm. Sellers were included on this basis regardless of whether they described their primary purpose to be turning a profit, the magnitude of the profit, or of whether they made a profit on any specific sale.

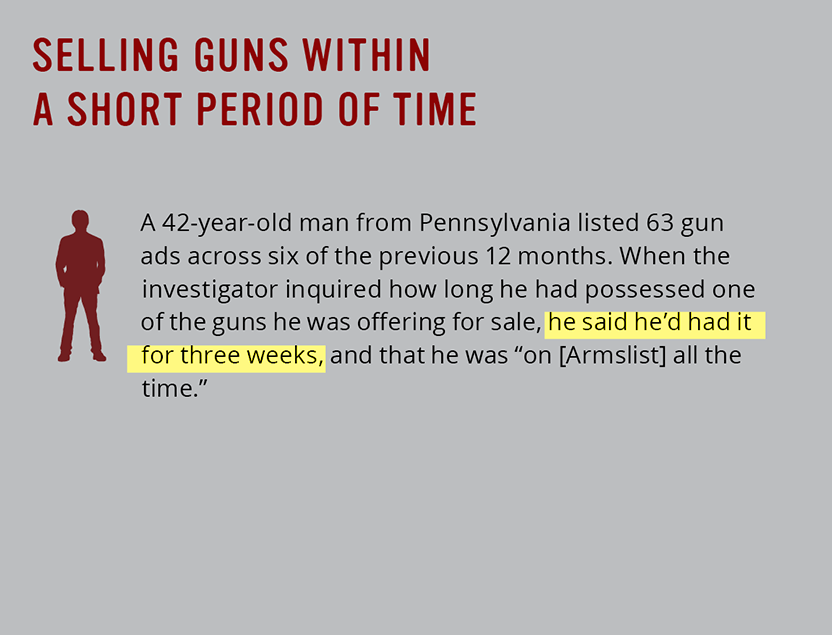

- Courts interpreting the “engaged in the business” standard have looked specifically at the speed with which defendants purchase and re-sell guns.24A federal circuit court found it to be probative of “engaging in the business” that a defendant engaged in a rapid sequence of purchasing and reselling firearms (a “buy-fly-resell pattern”). United States v. Tyson, 653 F.3d 192 (3rd Cir. 2011). For the purposes of the study, a seller was determined to be re-selling guns shortly after purchasing them if he or she clearly indicated a gun was being offered for resale less than one month after purchasing it.

- The “engaged in the business” statute covers the “purchase and resale” of firearms, and excepts any seller who exclusively sells from his or her “personal collection.” Interpreting the standard in practice, courts have examined whether defendants are selling unused firearms.25In one circuit court case, incriminating evidence of “engaging in the business” was found where a seller was offering firearms new and in their original packaging. United States v. Day, 476 F.2d 562 (6th Cir. 1973). In a federal district court case, the court distinguished “personal guns” from “brand new guns,” finding that the seller was incriminated by evidence that the latter guns were available for sale. United States v. Approx. 627 Firearms, 589 F. Supp. 2d 1129 (S.D. Iowa 2008). Another circuit court found it probative to establish the “engaging in the business” factors that a defendant discussed guns “coming in” and “brand new” — and “thus refer[ed] to a source of firearms other than his personal collection.” United States v. Brenner, 481 F. App’x 124 (5th Cir. 2012). For the purposes of the study, a seller met this threshold if he or she offered or consummated the sale of any firearm that was brand-new, in its original packaging, or otherwise unfired and in mint condition. Sellers were not included on the basis of offering new guns for sale if the guns had been lightly used or were otherwise being sold merely along with (but not still enclosed in) their original packaging.

Investigators called respondents until they achieved a sample of 50 from each group. Included sellers had to affirm or deny at least two of the four examined criteria to be included in the sample. All sellers contacted during the investigation described themselves in their gun ads as unlicensed sellers. If during the conversation a seller offered evidence that he or she was a licensed dealer, or if his or her name or phone number matched identifiers listed in ATF’s public database of licensed dealers, they were excluded from the analysis.26Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives: Listing of Federal Firearms Licensees (FFLs) – 2015, available at http://1.usa.gov/1Oq8PxT. While each conversation was different, the script prompted the seller to provide evidence as to whether they met each factor in over 90 percent of conversations.

The Underground Gun Market

The first pattern that emerges from “engaged in the business” prosecutions is the connection between unregulated gun sales and elevated rates of gun crime and violence. As a whole and individually, the analyzed cases show that “engaging in the business” is closely linked with gun-running across state and national borders, deliberate trafficking to or by felons, and reliance at least in part on existing marketplaces well known for unlicensed gun sales without background checks.

Trafficking Across Borders

Of the 253 cases prosecuted nationwide in 2011 and 2012, 48—nearly 1 in 5—involved guns that were allegedly trafficked from one state to another or across national boundaries. This is consistent with decades of research showing that public safety in states with strong laws is frequently undermined by guns purchased in and trafficked from other states with weaker laws.27Brian Knight, “State Gun Policy and Cross-State Externalities: Evidence from Crime Gun Tracing,” The American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 5(4), 200-229 (2013), available at http://bit.ly/20Kr5Xg. Of 170,000 firearms recovered by U.S. law enforcement agencies and successfully traced in 2014, 48,000 were recovered in different states than where they had been purchased—29 percent. In a 2009 report Trace The Guns, Mayors Against Illegal Guns showed that these interstate trafficking flows reflected the strength of the states’ respective gun laws: states that exported the largest number of guns to other states had the fewest sensible regulations on the books.28Everytown for Gun Safety, “Trace The Guns,” available at http://every.tw/1SG8CG7.

Thirty-nine cases (15 percent) involved allegations of trafficking guns from one state to another, and they illustrate some geographic patterns in the trafficking flows of guns within the country. According to prosecutors in those cases, guns destined for New York followed the “iron pipeline”—originating in states including Alabama,29United States v. Hudson, No. 1:11-cr-00181 (S.D.N.Y. 2011). Florida,30United States v. Brannigan et al, No. 1:12-cr-00716 (S.D.N.Y. 2012) Georgia,31United States v. Muhammad et al, No.1:11-cr-00488-ODE-CMS (N.D. Ga. 2011). South Carolina,32United States. v. Brown, No. 1:12-cr-00344 (S.D.N.Y. 2012). North Carolina,33United States v. Bent et al, No.1:11-cr-00605 (S.D.N.Y. 2011). Virginia,34United States v. Goodman, No.1:11-cr-00741 (S.D.N.Y. 2011). and Pennsylvania,35United States v. Delarosa, No. 1:12-cr-00664 (E.D.N.Y. 2012) and then following the I-95 highway north. Guns destined for California originated in such states as Nevada36United States v. Fregoso, No. 2:11-cr-00058-WBS (E.D. Cal. 2011). and Arizona.37United States v. Garcia-Perez, No. 3:12-cr-04062-JLS (S.D. Cal. 2012). And guns destined for Chicago’s streets originated across the border in Indiana.38United States v. Bell et al, No. 1:12-cr-00264 (N.D. Ill. 2012). In one particularly notorious case, a man purchased more than 200 guns from unlicensed sellers at gun shows in Indiana and then carried them back to Illinois where he sold them to criminals and gang members. Among them was a gun used in a May 2012 shooting. When asked during the trial whether he cared that he was selling firearms to individuals planning on committing crimes, the defendant responded, “Am I supposed to care?”39Transcript of Recordat 1113, United States v Tanksley, No. 1:12-cr-00354 (N.D. Ill. 2012).

The cases also highlighted the United States’ role as a source for illegal guns worldwide: at least 16 cases (six percent) involved guns entering or leaving the country. Among the alleged destinations of guns identified in the cases were Anguilla,40United States v. Gumbs, No. 1:12-cr-20742-WPD (S.D. Fla. 2012). Canada,41United States v Vachon, No. 1:12-cr-00062-SM (D.N.H. 2012). China,42United States v. Lin, No. 1:12-cr-00271 (EDNY 2012). Colombia,43United States v. Villa Carvajal, No. 1:12-cr-20272-PAS (S.D. Fla. 2012). Guatemala,44United States v. Chavez, No. 2:12-cr-20039-KHV (D. Kan. 2012). Haiti,45United States v. Romelus, No. 1:11-cr-60087-PAS (S.D. Fla. 2011). Mexico,46United States v. Chavez, No. 2:12-cr-20039-KHV (D. Kan. 2012). Nicaragua,47United States v. Chavez, No. 2:12-cr-20039-KHV (D. Kan. 2012). the Philippines,48United States v. Valencia, No. 2:12-cr-0259-GMN-CWH (D. Nev. 2012). and Venezuela.49United States v. Hinestroza, No. 1:12-cr-20255-UU (S.D. Fla. 2012). In one such case, the defendant conspired with others to sell firearms in Anguilla. He pleaded guilty to charges involving shipping ten guns and ammunition via the US Postal Service to the territory, and allegedly had sent prior shipments, as well. According to the indictment, nine of the ten weapons had obliterated or missing serial numbers.50United States v Gumbs, No. 1:12-cr-20742-WPD (S.D. Fla. 2012).

Trafficking to Criminals

The cases also show that—whether out of deliberate malfeasance or abundant disregard—people illegally “engaging in the business” put guns in the hands of criminals, drug offenders, and cop-killers.

At least 128 prosecutions (32 percent) involved a gun with an obliterated or missing serial number. Since 1968 guns are required to be manufactured with serial numbers so that they can be traced by law enforcement if they are recovered at crime scenes, but criminals attempt to obliterate the numbers to make it difficult to follow the gun’s pathway. Accordingly, ATF has long observed that this is an indicator of firearms trafficking,51The Department of the Treasury and Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco & Firearms, “Following The Gun,” 5 (2000), available at http://every.tw/1knbegX. and it is a federal crime to be in possession of such a weapon.5218 U.S.C. § 922(k). The high share of engaging in the business cases involving such weapons—nearly one in three—is indicative of how closely the alleged behavior is linked with subsequent criminal offending.

Thirty percent of defendants charged with engaging in the business were also charged with illegal firearm possession,5318 U.S.C. § 922(g). indicating that they themselves had a prior criminal or domestic violence history or otherwise met criteria that barred them from owning guns, and 27 percent were charged with a drug charge,54Under Title 21, Chapter 13. indicating alleged illegal use or possession. Seventy prosecutions (17 percent) involved firearms that had been stolen.

Gun Transfers in Markets Known for Unlicensed Sales

It was notable that in 24 cases — almost 1 in 10 — defendants relied on marketplaces known for unlicensed sales such as gun shows, online websites or print advertisements to buy or sell their goods.

ATF identified gun shows as a “major trafficking channel” in their 1999 examination of trafficking investigations Following The Gun, and determined that their investigations at gun shows during the period they examined involved approximately 26,000 diverted firearms.55The Department of the Treasury and Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco & Firearms, “Following The Gun,” xi (2000), available at http://every.tw/1knbegX. These investigations demonstrate that this is still the case—17 cases (seven percent) involved gun shows. In a particularly harrowing example, a seller offered guns at gun shows over a period of eight years, selling as many as 20 a day. Guns he sold were later recovered at several crime scenes, and a week after he sold a gun at a gun shows in Puyallup, WA, a violent criminal used it to shoot two Seattle Field Training Officers, killing one of them.56Momfort Charge in ‘one-man war’ against Seattle Police Force, Komo News, Nov. 12, 2009, available at http://bit.ly/1OC1ADB. It was not until a year after the shooting that police arrested the seller, who ultimately pleaded guilty to “engaging in the business.” At sentencing, Assistant U.S. Attorney Jenny A. Durkan summed up the seller’s practices: “Defendant lined his pockets by funneling guns to criminals, and others paid the heavy price for his actions.”57United States v. Devenny, No. 3-11-cr-05235-BHS (W.D. Wash. 2011).

The prosecutions also demonstrated how the internet has changed gun trafficking: in a number of cases, the defendants used online forums to buy or sell firearms. In one example, the defendant sold guns out of his screen-printing business, which he advertised on GunsAmerica.com, disposing of 130 firearms in the year before his conviction.58United States v. Burke, No. 3:12-cr-00281-M (N.D. Tex. 2012). In another, the defendants sold guns via the forum GunBroker.com as well as over sixty gun shows.59United States v. Valdes, No. 9:12-cr-80234-DMM (S.D. Fla. 2012) In a third, the defendant advertised his guns on the social-networking website LinkedIn.com, where he listed himself as the CEO of “Master Gunsmiths.” Only after undercover investigators had made several purchases from him was he arrested.60United States v. Aquino, No. 1:11-cr-20869-PCH (S.D. Fla. 2011).

Recent research conducted by Everytown both nationally and at the state level has shown that criminals readily acquire guns in online markets. Undercover investigations of the population of buyers shopping for guns online have consistently shown that more than 1 in 30—and in some states as high as 1 in 10—are prohibited from possessing firearms due to a prior criminal history or domestic violence conviction.61Everytown for Gun Safety, “Felon Seeks Firearm, No Strings Attached,” available at http://every.tw/1Mmj2bv; Everytown for Gun Safety, “No Questions Asked,” available at http://every.tw/1QgseCn; Everytown for Gun Safety, “Online and off the Record,” available at http://every.tw/1Qgstxk. Repeatedly, felons and abusers have used online markets to avoid background checks and arm themselves, and then used the firearms to kill intimate partners and children.62Everytown for Gun Safety, “Valerie, Shayley, Samantha, Sharon, Monique, Zina and Jitka,” Aug. 13, 2015, available at http://every.tw/1NHZDnK.

The Deadly Cost of “Engaging in the Business”

A Tennessee Man Who Traded a Gun to a Cop-Killer

On April 2, 2011 in Chattanooga, TN, a convicted felon—who was prohibited from buying or possessing guns under federal law—shot and killed Officer James Chapin with a gun that he got from an unlicensed seller at a gun show. Officer Chapin, a 27-year veteran of the service, was responding to a report of a pawnshop robbery at the time.63Funeral Services Today for Sgt. Tim Chapin, WRCBtv.com, April 5, 2011 available at http://bit.ly/1HGaeck; Plea Agreement at 3, United States v. Dawson, No. 1:12-cr-00065 (E.D. Tenn. 2012). A subsequent investigation revealed that the murderer had traded for the gun from a person who sold guns frequently, and the ATF warned the seller that he needed to get a federal firearms license.64Plea Agreement at 3, United States v. Dawson, No. 1:12-cr-00065 (E.D. Tenn. 2012).

The seller did not heed the request and in October, ATF agents learned that the man was continuing to sell firearms without a license. ATF initiated an undercover operation in February 2012 that revealed the man went to gun shows to purchase firearms and subsequently resold them, often at gun shows as well.65Plea Agreement at 3-6, United States v. Dawson, No. 1:12-cr-00065 (E.D. Tenn. 2012); Complaint atA-5-A-7, United States v. Dawson, No. 1:12-cr-00065 (E.D. Tenn. 2012). Upon his arrest in May 2012, the man confessed that his livelihood depended on selling firearms and that he and his father-in-law, one of his co-defendants, had an inventory worth $60,000.66Plea Agreement at 3-6, United States v. Dawson, No. 1:12-cr-00065 (E.D. Tenn. 2012).

The seller was tried along with three co-defendants, to whom he referred buyers for specific requests. Over a period of less than two years, the man had purchased almost 60 firearms from gun dealers and later re-sold them.67Plea Agreement at 3-6, United States v. Dawson, No. 1:12-cr-00065 (E.D. Tenn. 2012). The defendants advertised firearms for sale in print publications and sold numerous firearms to undercover ATF agents.68Indictment at 3, United States v. Dawson, No. 1:12-cr-00065 (E.D. Tenn. 2012).

The seller pled guilty to conspiracy to “engage in the business” of selling firearms without a license and was sentenced to 34 months in prison.69Judgment at 1-3, United States v. Dawson, No. 1:12-cr-00065 (E.D. Tenn. 2012). But two of his co-defendants were acquitted of the “engaging in the business” charges.70Judgment as to Carl Monroe at 1, United States v Monroe, No. 1:12-cr-00065 (E.D. Tenn. 2012)(acquitted on 922(a)(1)(A) charge, but convicted of selling firearm to a prohibited person); Judgment of Acquittal as to Richard Monroe at 1, United States v Monroe, No. 1:12-cr-00065 (E.D. Tenn. 2012).

A Biker Gang that Trafficked Guns from Florida to New York City

Following a two-year investigation, police arrested eight members of three Brooklyn biker gangs—the Forbidden Ones, the Dirty Ones, and the Trouble Makers—and charged the leader of the scheme with unlawfully “engaging in the business” of dealing firearms. The gang members allegedly sold 40 firearms, ammunition, and weapons — including an operational cannon—to a confidential informant and undercover NYPD and ATF officers. At the time of the arrest, law enforcement recovered another 20 firearms, explosive devices, and drugs. Some of these were stored in a home where the defendant’s wife ran a daycare center.71Press Release, United States Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of New York, Eight Members of Three Brooklyn-based Motrocycle Ganes Charged Federally with Trafficking of High Caliber Weapons (Oct. 16, 2012) available at http://1.usa.gov/1HvCmEs;Complaint and Affidavit at 1-13, United States v Brannigan, 1:12-cr000716 (E.D.N.Y. 2012).

According to the arrest affidavit, in several cases the gangs acquired the guns in Florida and trafficked them to New York City. The leader of the scheme traveled to Florida on separate occasions to retrieve at least 10 firearms with the intention of selling them in New York City.72Complaint and Affidavit at 6-7, United States v Brannigan, 1:12-cr000716 (E.D.N.Y. 2012). If not for the investigation, all of these weapons would have likely ended up in the city’s black market.

The defendant pled guilty to selling guns without a license and was sentenced to three years probation.73Judgment at 3, United States v Brannigan, 1:12-cr000716 (E.D.N.Y. 2012).

Trafficking Out-of-State Guns to Career Criminals in Chicago

Between 2008 and 2012, an unlicensed seller bought more than 200 guns in Indiana and returned to Illinois where they were sold to criminals and other dangerous individuals for a significant profit. He often bought the guns from other unlicensed sellers, at least one of whom required nothing more than an Indiana identification card to make purchases.74Govt. Sentencing Mem., United States v Lewisbey, 1:12-cr-00354 (N.D. Ill. 2012)

Many of the guns that went through his hands ultimately found their way to convicted felons. Chicago law enforcement officials recovered guns he trafficked to their city from members of the Gangster Disciples street gang, and one gun was used to shoot two people in May 2012.75Govt. Sentencing Mem., United States v Lewisbey, 1:12-cr-00354 (N.D. Ill. 2012) During the trial, when asked whether he cared that he was selling firearms to an individual planning to commit crimes, the defendant responded, “am I supposed to care?”76Transcript of Record at 1113, United States v Lewisbey, 1:12-cr-00354 (N.D. Ill. 2012).

He was charged with “engaging in the business” of dealing in firearms, unlawful transportation of firearms, and crossing state lines with the intent to engage in the unlicensed dealing of firearms. He was found guilty of all charges and sentenced to 200 months imprisonment.77Judgment at 1, United States v Lewisbey, 1:12-cr-00354 (N.D. Ill. 2012).

A Heavy Price

On Halloween night 2009, 39-year-old Seattle Field Training Officer Timothy Brenton wanted to take his two kids trick-or-treating but he was scheduled to work.78Natasha Chen, Britt (Sweeney) Kelly Testifies in Chris Monfort Murder Trial, KIRO7. com, Feb. 18, 2015 available at http://bit.ly/1RMazA5. Around 10:00 p.m., Brenton and a student officer, Officer Britt Sweeney, were in a parked police car when another vehicle drove up, blocked them in, and opened fire, injuring Sweeney and killing Brenton.79Seattle Police Officer Murder Suspect Paralyzed, King5.com, Nov. 13, 2009 available at http://kng5.tv/1ljmefo.

The murder weapon was allegedly obtained just one week earlier at a gun show in Puyallup, WA. According to the Government’s Sentencing Memorandum, the gun was sold by a man who had been dealing firearms without a license for eight years, re-selling guns he’d purchased for a quick profit—and had “flooded the streets with untraceable firearms.” A regular at gun shows, he displayed as many as 20 a day and bragged to an undercover agents about selling 14 guns at one show. He told an undercover ATF agent that he knew he had sold the gun used to kill Officer Brenton, but expressed little regard for whether or not his guns fell into the hands of criminals. He explained to the agent that he had a “don’t ask, don’t tell” policy.80Govt. Sentencing Mem. at 5, United States v Devenny, 3:11-cr-05235-BHS (W.D. Wash. 2011).

This was not the first time a gun sold by the man was allegedly used to commit a crime. The ATF traced guns sold by him to at least two other crime scenes. Between the time of the officer’s murder and the defendant’s arrest, he sold guns to at least two more people prohibited from possessing firearms—a convicted felon and a person with a domestic violence conviction.

On November 19, 2010, police arrested the seller, who ultimately pleaded guilty to “engaging in the business” as well as selling a firearm to a prohibited person, and was sentenced to 18 months in prison and three years of supervised release. Assistant U.S. Attorney Jenny A. Durkan summed up his practices: “Defendant lined his pockets by funneling guns to criminals, and others paid the heavy price for his actions.”81Press Release, United States Attorney’s Office for the Western District of Washington, Olympia Man Sentenced to Prison for Illegal Gun Sales (March 19, 2012) available at http://1.usa.gov/1M4Gie0.

A Federal Statute in Need of Clarification

In the absence of a stand-alone federal gun trafficking statute, law enforcement officers rely on the “engaging in the business” offense to go after gun traffickers. Our analysis of federal prosecutions suggests that due to a lack of clarity as to what qualifies as “engaging in the business,” this process is undermined at every stage. Prosecutors bring charges in a disproportionately low share of the cases; cases they prosecute result in a dismissal over one-third of the time; and defendants whose cases go to trial are acquitted nearly half the time.

Disproportionately Low Rates of Prosecution

An analysis of prosecution data obtained from the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse (TRAC) revealed that the prosecution rate for selling guns without a license is notably low when compared to prosecution rates for drug trafficking and for other firearm crimes.

When law enforcement referred a case to prosecutors and the lead charge was selling guns without a license, prosecutors accepted that case for prosecution only about half (54 percent) of the time.

By contrast, when drug trafficking8221 U.S.C § 841. was the lead charge, over three-quarters (77 percent) of the referrals resulted in indictments. Given that selling guns without a license is the crime used to prosecute gun traffickers, a comparison to drug trafficking prosecutions is particularly relevant and revealing of the government’s disinclination to prosecute this offense.

The prosecution rate for selling guns without a license is also significantly lower than the average prosecution rate for all firearm crimes.83Under Title 21, Chapter 44. Over two-thirds (67 percent) of firearms crimes are accepted for prosecution.84Rate of prosecution calculated to be (number disposed of cases that were prosecuted/number of disposed of cases).

High Rates of Dismissal

TRAC is a useful tool for determining prosecution rates, but it is limited by the fact that prosecutions are categorized by lead charge only, and do not capture prosecutions in which selling guns without a license was charged but was not the lead charge.85TRAC employs the following definition of lead charge: “Different data systems use different criteria for determining which of the charges to pick as the most serious or lead charge. The U.S. Courts and the U.S. Sentencing Commission use the charge with the maximum statutory penalty that can be applied; the U.S. Prisons classify by the most serious penalty in fact applied. The federal prosecutors use a more subjective rule: ‘the substantive statute which is the primary basis for the referral’ where primary is left for determination to the individual assistant U.S. attorney who is assigned the case. Note also that the classification takes place at the time the referral is received. It is thus possible that the defendant may not ultimately be prosecuted on this charge.”, see, TRAC: About Us, Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, Syracuse University, http://bit.ly/1HFr8rA (last visited Oct. 29 2015). Everytown’s review of each federal prosecution that involved a charge of selling guns without a license may shed some light on why this crime is prosecuted at a disproportionately low rate.

The research reveals that nearly one-third (30 percent) of defendants charged with selling guns without a license are ultimately not convicted of that charge. Moreover, when defendants accused of selling guns without a license went to trial by jury, they were convicted of that charge only about half (53 percent) of the time, indicating that inconsistent application of the standard makes it difficult to anticipate what type of conduct qualifies as “engaging in the business.”

As a result, sellers get away with feeding the criminal market by selling large numbers of guns without background checks. For example, one high-volume seller who went to trial was found not guilty of engaging in the business of selling guns without a license despite the fact that he had sold over 400 guns, made $50,000 per year from gun show sales, and was warned twice by ATF that he needed to get a license. In the words of the seller’s defense attorney, “You know, it would be easy if we had a law that says you can sell 50 firearms in a year, or 10 firearms or 100, but that’s not what it is. It depends upon the purpose of the fellow selling the firearms.” More examples are illustrated on pages 16 and 17.

Prominent Geographic Variation in Where Cases are Brought

Notably, the rate at which “engaged in the business” cases are brought by federal prosecutors varies widely across districts. This may be influenced by district size and underlying levels of gun trafficking, but also by efforts made by local law enforcement and prosecutors.

Of the 94 federal judicial districts, 49 brought charges against defendants for “engaging in the business” during the period of observation — just over half. Cases were further concentrated within those districts: just seven courts accounted for over 48 percent of cases.86United States Courts: Federal Judicial Caseload Statistics, “Table D-3-U.S. District Courts – Criminal Defendants Filed by Offence and District ,” (Mar. 31, 2011), available at http://1.usa.gov/1HveLDJ United States Courts: Federal Judicial Caseload Statistics, “Table D-3-U.S. District Courts – Criminal Defendants Filed by Offence and District ,” (Mar. 31, 2011), available at http://1.usa.gov/1HveLDJ; Data is available annually for the year April 1-March 31; Everytown estimated the caseload during that period of observation as the annual average of the period April 1, 2010-March 31, 2012.

To assess rates of prosecution independent of the size of the district and underlying variation in criminal activity, we compared the number of defendants prosecuted for “engaging in the business”, controlling for the criminal caseload of each court, as provided by the Bureau of Justice Statistics.87S.D. Ga., S.D.N.Y., S.D. Fla., N.D. Ga., E.D.N.Y., S.D. Ohio, and E.D. Cal. On average, in the 49 districts with cases, “engaged in the business” defendants represented just 0.4 percent of the total criminal caseload. The Southern District of Georgia had by far the highest rate, where defendants accused of “engaging in the business” accounted for an estimated 2.7 percent, and the Northern District of Georgia was not far behind at an estimated 1.5 percent.

The elevated rate in the region was almost certainly the result of several law enforcement operations conducted around the period of observation that specifically targeted illegal gun trafficking. In “Operation Fox Hunt,” conducted by the Richmond County Sheriff’s Office and ATF between 2009 and 2011, undercover agents purchased or recovered more than 192 firearms and indicted 75 defendants.88Department of Justice, Southern District of Georgia, “71 Defendants Charged with Gun and Drug trafficking Offenses After Undercover Investigation,” Mar. 15, 2011, available at http://bit.ly/1MJoaDU. In “Operation Trap Door,” conducted by Atlanta police and ATF and concluded in June 2012, agents recovered 270 guns including 45 that were stolen and expected to indict 40 defendants.89Kimathi Lewis, “Storefront Sting Nets 270 illegal Firearms, Drugs and 60 Suspects,” Examiner.com, Jun. 28, 2012, available at http://exm.nr/1O1YZzR. And in “Operation Smoke Screen,” which ran for seven months beginning in August 2011, the Richmond County Sheriff’s Office and ATF recovered 64 firearms and resulted in 15 indictments on federal firearm offenses.90Press Release, United States Attorney’s Office for the Southern District of Georgia, 24 Defendants Charged with Gun Offenses After Undercover Investigation, Feb. 28, 2012, available at http://bit.ly/1M4N6s4; United States v. Wright, No. 1:12-cr-00060 (S.D. Ga. 2012); U.S. v. Swint, No. 1:11-cr-00056-DHBWLB (S.D. Ga. 2011); United States v. Anderson, No. 1:12-cr-00041-DHB-BKE (S.D. Ga. 2012). In total, these operations accounted for 22 cases documented in this research including 32 defendants—over half of the “engaged in the business” cases brought in the Northern and Southern Districts of Georgia during this period.

High-volume Gun Sales But No Convictions

Below are several instances of high volume sellers making it to trial, but having their cases dismissed due to weak phrasing in the current definition of the law.

Acquitted: A Florida Man Who Sold Hundreds of Guns and Made Tens of Thousands of Dollars

In 2011, following an ATF investigation, federal agents charged a Florida man with “engaging in the business” of dealing firearms without a license.

By his own estimation, the defendant sold more than 400 guns between 2006 and 2010 and attended as many as 25 gun shows per year.91Transcript of Record at 26, United States v Fries, No. 4:11-cr-00022-RH-WCS (N.D. Fla. 2011). The defendant also acknowledged that he earned $30,000 to $50,000 from the sales in certain years.92Id. at 26. But he argued that despite the sheer volume of sales, the defendant fit into the exception that allows hobbyists to make sales without getting a license. Despite the volume of the sales he conducted and the profit he earned, the jury ultimately acquitted the defendant.

In his opening remarks, the defense attorney argued that the lack of a numeric threshold in the statute required that his client be acquitted: “You know, it would be easy if we had a law that says you can sell 50 firearms in a year, or 10 firearms or 100, but that’s not what it is. It depends upon the purpose of the fellow selling the firearms.”93Id. at 34

Acquitted: A Man Who Sold 25 Guns to a Convicted Felon

During an ATF investigation, the defendant allegedly sold 25 firearms to a confidential informant, despite the fact that the informant told the defendant that he was a convicted felon.94Transcript of Record at 9, 12, United States v. Bradley, No. 1:12-cr-00036-MRB (S.D. Ohio 2012).

According to the prosecution’s opening statement, the defendant stated that he did not know how many guns he had sold, but admitted that he “used the money [from his sales] to purchase more guns and to pay bills.” He said that he had made $6,000 in one transaction and sold $20,000 worth of guns to a single individual.95Id. at 12.

In his opening statement at trial, the defendant’s lawyer argued that the vague nature of the “engaged in business” standard made it difficult to convict the defendant: “No one in this case will tell you that the law says what the frequency of sales puts you in the business of selling guns…There is no specific frequency that triggers engaging in a business. There is no specific amount of money that triggers engaging in the business. It’s a much more complicated definition than that.”96Id. at 17.

A jury found the defendant not guilty of dealing firearms without a license.

Dismissed: A Man Who Routinely Offered Scores of Guns for Sale, Including Several Recovered at Crime Scenes

In 2010 and 2011, the ATF recovered multiple guns at crime scenes in Texas and California and traced them to an unlicensed seller who had bought them from an Alabama gun dealer just a few months prior, suggesting that he resold them shortly after purchasing them.97Trial Memorandum of United States at 3, United States v. Nowka, No. 5:11-cr-00474-VEH-HGD (N.D. Ala. 2011).

The ATF launched an undercover investigation and bought firearms from the defendant at five gun shows. According to the prosecution’s trial memorandum, the defendant offered approximately 75 guns for sale at a single show in Muscle Shoals, Alabama.98Id. Undercover ATF agents purchased several guns from the defendant. Traces on these guns revealed that the defendant had purchased these guns less than three months prior to re-selling them.99Id. at 4.

Prosecutors charged the defendant with multiple crimes including “engaging in the business,” but later dropped that charge.

A Better Definition Of “Engaging in the Business”

Data drawn from a year’s worth of gun ads posted by unlicensed sellers in the country’s largest online gun market shows that while the majority of sellers offer just one or two firearms for sale annually, a tiny share of sellers offer guns in high volumes—up to 150 guns in a single year. Moreover, sellers operating at this volume appear to be qualitatively different from the other more casual sellers: they are three times more likely to meet other factors indicating they are unlawfully “engaged in the business” of dealing firearms without a license.

A Small Share of High-Volume Gun Sellers

The 644,715 gun ads scraped from Armslist.com during the study-period could be linked to 383,828 self-described unlicensed sellers, the vast majority of whom did not appear to post more than one or two ads. Sellers that posted one or two ads accounted for 88 percent of observed users and were linked to 61 percent of total ads.

But a tiny fraction of sellers were observed posting ads at higher volumes

and accounted for a disproportionate share of the total market. At the upper end of the spectrum, 684 users each posted 25 or more ads during the year (and as many as 150), accounting for 27,874 gun ads in total. Although they represented 1 of 561 users (0.2 percent) they accounted for 1 in 23 gun ads (4.3 percent).

A High Likelihood of “Engaging in the Business”

Individuals offering 25 or more firearms appeared to differ from more casual sellers. Specifically, they were more likely than not to meet multiple factors for unlawfully “engaging in the business” of selling firearms, whereas few low-volume sellers did.

Investigators were successful in eliciting evidence of each factor from more than 92 percent of respondents. For each factor, high-volume sellers were more likely to confirm that they fulfilled it than were low-volume sellers. In total, high-volume sellers were three times more likely than low-volume sellers to offer evidence they met multiple factors for “engaging in the business.”

Limitations

While we took all possible measures to separate low- and high-volume sellers in our sample, a few respondents who appeared to sell guns only casually (based on the volume of observed online ads they posted) indicated during their interviews that they may actually conduct a regular stream of commerce. For example, a respondent in Illinois who was linked to 13 ads proclaimed that he had conducted over 100 transactions on Armslist, either buying or selling. For the purposes of the experiment, when we mistakenly include a true high-volume seller in the group of low-volume sellers, we reduce the perceived differences between the two groups. As a result, this study likely underestimates the difference between low- and high-volume sellers.

Neither this study, nor any other, can take the full measure of unlicensed gun sales in the U.S., which occur online but also take place at countless gun shows and in tens or hundreds of thousands of one-off transfers between buyers and sellers. But just as prosecutions of “engaging in the business” crimes offer a glimpse of the larger world of unlawful gun sales, data from online gun ads provide unique insights into the dynamics of unlicensed gun sales more broadly. As the host of more than half-a-million ads each year, Armslist accounts for a significant share of total unlicensed firearms sales in the U.S. — more than any other single marketplace.

This study was designed to measure differences between sellers offering more than 25 guns per year and those offering fewer. While the results show that those above the threshold are more likely than not to exhibit multiple factors for “engaging in the business,” they do not discount the possibility that sellers operating at slightly lower thresholds also meet these criteria. Therefore, this study provides a conservative bar at which a numeric standard for “engaging in the business” might be established.

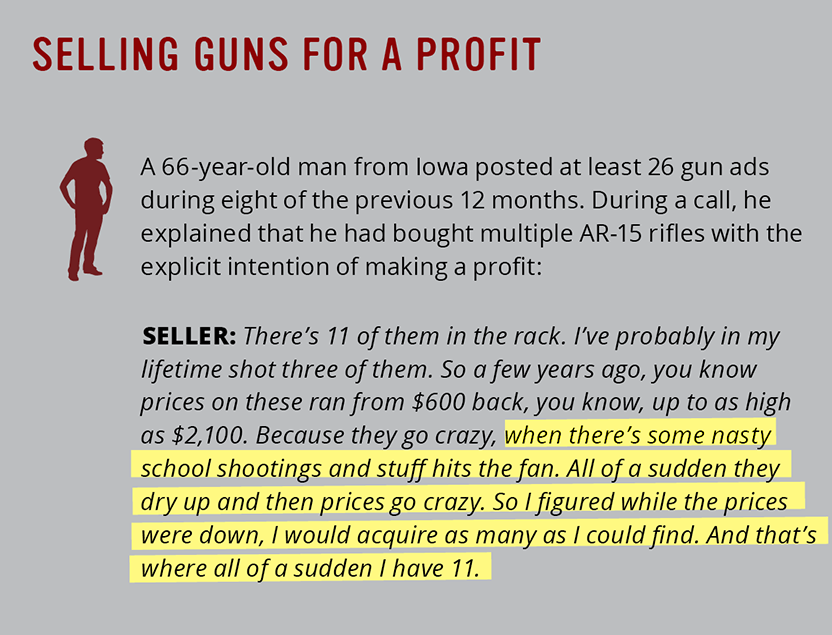

Examples From Undercover Calls With High-volume Sellers

Recommendations

The Administration should issue a regulation that clarifies the “engaged in the business” standard. Such a regulation would clarify for gun sellers whether they need to get a federal firearms license—and consequently comply with all dealer regulations and conduct background checks. And it would put teeth into the federal statute that law enforcement use to prosecute gun traffickers and high-volume sellers who feed the criminal market.

An “engaged in the business” regulation should clarify and define key terms by:

- Codifying a multi-factor test. The regulation should codify the factors that courts use to determine if a person is “engaged in the business” of selling firearms. These common-law factors include selling guns unused or still in their original packaging, the repetitive sale of guns, selling guns for profit, re-selling guns shortly after obtaining them, selling multiple guns of the same make and model, and expressing a willingness or ability to obtain guns upon request.

- Creating a numerical inference. The definition should also include an inference that a person who sells or offers for sale a given number of guns is “engaged in the business” of selling firearms. Everytown’s research shows that a person who sells or offers for sale 25 or more guns in one year is more likely than not to exhibit multiple indicators of being engaged in the business—and over three times more likely than a person who offers 25 or fewer guns for sale.

- Defining “occasional sales.” The current statute specifies that a person who makes “occasional sales, exchanges, and purchases” is not “engaged in the business” of selling firearms and need not get a license. A regulatory limit on how many guns can be sold in “occasional sales” would cap the number of guns a hobbyist can sell in a year, while still allowing people to liquidate their personal collection of firearms as described below. The legislative history suggests this exception was intended to apply only to people who were selling just a few guns.

- Defining “personal collection.” The statute also specifies that a person who “sells all or part of his personal collection of firearms” is not “engaged in the business” of selling guns. The term “personal collection” should be defined to include only those firearms obtained for a person’s own personal use, and not those obtained for the purpose of selling or trading. The definition should also clarify that, as with dealer-owned firearms, guns are not considered a part of a person’s personal collection until the owner has possessed them for at least one year, unless they were obtained through inheritance.

Learn More:

Everytown Research & Policy is a program of Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, an independent, non-partisan organization dedicated to understanding and reducing gun violence. Everytown Research & Policy works to do so by conducting methodologically rigorous research, supporting evidence-based policies, and communicating this knowledge to the American public.