The Impact of Gun Violence on Children and Teens

Last Updated: 2.20.2023

Introduction

When Davonte was asked what he wanted for his birthday, he didn’t ask for a big celebration, he only said, “I’m glad I made it to see 18.” He was shot and killed less than one week after turning 18. He had previously spoken before the Baltimore City Council on youth violence prevention.

Key Findings

The Deadly Impact of Guns on Children and Teens in America

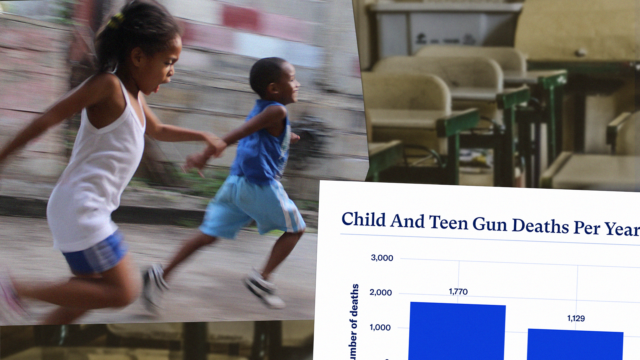

Annually, nearly 4,000 children and teens (ages 0 to 19) are shot and killed, and 15,000 are shot and wounded—that’s an average of 53 American children and teens every day.1Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. WONDER Online Database, Underlying Cause of Death. A yearly average was developed using four years of the most recent available data: 2018 to 2021. Children and teens aged 0 to 19. Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, “A More Complete Picture: The Contours of Gun Injury in the United States, December 2020, https://everytownresearch.org/report/nonfatals-in-the-us/. And the effects of gun violence extend far beyond those struck by a bullet: An estimated three million children witness a shooting each year.2Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Shattuck A, Hamby SL. Prevalence of childhood exposure to violence, crime, and abuse: results from the National Survey of Children’s Exposure to Violence. JAMA Pediatrics. 2015;169(8):746-54. Everytown analysis derives this number by multiplying the share of children (aged 0 to 17) who are exposed to shootings per year (4%) by the total child population of the US in 2016 (~73.5M). Gun violence shapes the lives of the children who witness it, know someone who was shot, or live in fear of the next shooting.

Gun deaths among children and teens by intent

Last updated: 2.20.2023

Firearms are the leading cause of death for children and teens.3Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. WONDER Online Database, Underlying Cause of Death, Injury Mechanism & All Other Leading Causes. Data from 2021. Children and teenagers aged 1 to 19. This is a uniquely American problem. Compared to other high-income countries, American children aged 5 to 14 are 21 times more likely to be killed with guns, and American adolescents and young adults aged 15 to 24 are 23 times more likely to be killed with guns.4Grinshteyn E, Hemenway D. Violent death rates in the US compared to those of the other high-income countries, 2015. Preventive Medicine. 2019;123:20-26.

When American children and teens are killed with guns, 62 percent are homicides—nearly 2,500 deaths per year.5Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, WONDER Online Database, Underlying Cause of Death. A yearly average was developed using four years of the most recent available data: 2018 to 2021. Ages 0 to 19. Homicide includes shootings by police. Children are particularly impacted by the intersection of domestic violence and gun violence. For children under age 13 who are victims of gun homicides, 85 percent of those deaths occur in the home, and nearly a third of those deaths are connected to intimate partner or family violence.6Fowler KA, Dahlberg LL, Haileyesus T, Gutierrez C, Bacon S. Childhood firearm injuries in the United States. Pediatrics. 2017;140(1). Between 2015 and 2022, nearly two in three child and teen victims of mass shootings died in incidents connected to domestic violence.7Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund. Mass Shootings in America. https://every.tw/1XVAmcc. March 2023. Data drawn from 16 states indicate that nearly two-thirds of child fatalities involving domestic violence were caused by guns.8Adhia A, Austin SB, Fitzmaurice GM, Hemenway D. The role of intimate partner violence in homicides of children aged 2-14 years. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2019;56(1):38-46.

Another 33 percent of child and teen gun deaths are suicides—1,300 per year.9Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, WONDER Online Database, Underlying Cause of Death. A yearly average was developed using four years of the most recent available data: 2018 to 2021. Ages 0 to 19. And firearm suicide has been rising dramatically: Over the past decade, the firearm suicide rate among children and teens has increased by 66 percent.10Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. WONDER Online Database, Underlying Cause of Death. A percent change was developed using 2012–2021 crude rates for children and teens aged 0 to 19. For people of all ages, having access to a gun increases the risk of death by suicide by three times.11Anglemyer A, Horvath T, Rutherford G. The accessibility of firearms and risk for suicide and homicide victimization among household members: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2014;160(2):101-110. Research shows that an estimated 4.6 million American children live in homes with at least one gun that is loaded and unlocked.12Matthew Miller and Deborah Azrael, “Firearm Storage in US Households with Children: Findings from the 2021 National Firearm Survey,” JAMA Network Open 5, no. 2 (2022): e2148823, https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.48823. The combination of suicidal ideation and easy firearm access can be lethal. When children under the age of 18 die by gun suicide, they are likely to have used a gun they found at home: Over 80 percent of child gun suicides involved a gun belonging to a parent or relative.13Johnson RM, Barber C, Azrael D, Clark DE, Hemenway D. Who are the owners of firearms used in adolescent suicides? Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 2010;40(6):609-611.

Gun violence manifests in a myriad of ways in American schools, and school shootings have created new anxieties for the younger generation of students. According to an Everytown analysis, there have been at least 549 incidents of gunfire on school grounds from 2013 to 2019.14Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund. Keeping Our Schools Safe: A Plan for Preventing Mass Shootings and Ending All Gun Violence in American Schools. everytownresearch.org/school-safety-plan. February 2020. Of these, 347 occurred on the grounds of elementary, middle, or high schools, resulting in 129 deaths and 270 people wounded.15Everytown’s Gunfire on School Grounds database includes 201 incidents on colleges and universities. These incidents were excluded from analyses to focus on gunfire on K-12 school grounds. While mass shootings like the incident at Sandy Hook Elementary School—and, more recently, Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School and Santa Fe High School—are not commonplace, schools are more likely to experience gun homicides and assaults, unintentional shootings resulting in injury or death, and gun suicide and self-harm injuries. All incidents of gun violence in schools, regardless of their intent or victim count, compromise the safety of students and staff.

Children and teens who live in cities are at a significantly higher risk of gun homicides and assaults compared to their peers in rural areas. Ninety-two percent of all hospitalizations of children for firearm injuries occur in urban areas (counties with over 50,000 residents).16Herrin BR, Gaither JR, Leventhal JM, Dodington J. Rural versus urban hospitalizations for firearm injuries in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2018;142(2): e20173318. Everytown calculation from dividing the number of urban hospitalizations by the total number of hospitalizations. These injuries have lifelong consequences: Almost 50 percent of the wounded have a disability when they are discharged from the hospital.17DiScala C, Sege R. Outcomes in children and young adults who are hospitalized for firearms-related injuries. Pediatrics. 2004;113(5):1306–12. Fifteen- to 19-year-olds in urban areas are hospitalized for firearm assaults at a rate eight times higher than 15- to 19-year-olds in rural areas.18Herrin BR, Gaither JR, Leventhal JM, Dodington J. Rural versus urban hospitalizations for firearm injuries in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2018;142(2): e20173318. Children and teens from 15 to 19; Nance ML, Denysenko L, Durbin DR. The rural-urban continuum: variability in statewide serious firearm injuries in children and adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156(8):781-5. Urban and low-income youth are much more likely to witness gun violence than suburban and higher-income youth.19Stein BD, Jaycox LH, Kataoka S, Rhodes HJ, Vestal KD. Prevalence of child and adolescent exposure to community violence. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2003 Dec;6(4):247-64.

The Disproportionate Impact of Gun Violence on Black and Latinx Children and Teens

As with gun violence generally, impact among children and teens is not equally shared across populations. Black children and teens in America are 17 times more likely than their white peers to die by gun homicide.20Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. WONDER Online Database, Underlying Cause of Death. A yearly average was developed using five years of the most recent available data: 2016 to 2020. Children and teens aged 0 to 19, Black and white defined as non-Latinx origin. Homicide includes shootings by police. Black children and teens are 13 times more likely to be hospitalized for a firearm assault than white children.21Everytown for Gun Safety, “A More Complete Picture.” Latinx children and teens are 2.7 times more likely to die by gun homicide than their white peers.22Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. WONDER Online Database, Underlying Cause of Death. A yearly average was developed using four years of the most recent available data: 2018 to 2021. Ages 0 to 19. Latinx defined as all races of Latinx origin. White defined as non-Latinx origin. Homicide includes shootings by police.

White and Black children may live in the same city yet experience it differently. Due to policy decisions that enforce racial segregation and disinvestment in certain communities, gun violence is concentrated in Black neighborhoods within cities, many of which are marked by high levels of poverty and joblessness and low levels of investment in education.23Chandler A. Interventions for reducing violence and its consequences for young Black males in America. Cities United. 2016. https://bit.ly/2xGoNPG. A high concentration of these factors in a neighborhood is referred to as “concentrated disadvantage” and is a strong predictor of violent crime. Youth in neighborhoods that experience concentrated disadvantage can be isolated from institutions such as schools and jobs, increasing the risk that they will engage in crime and violence, thus feeding into this vicious cycle of violence.24Ibid.

Black and Latinx children in cities are exposed to violence at higher rates than white children. Exposure includes witnessing violence, hearing gunshots, and knowing individuals who have been shot. Black children in Columbus, OH, were exposed to 66 percent more violence, on average, than white children.25Browning CR, Calder CA, Ford JL, Boettner B, Smith AL, Haynie D. Understanding racial differences in exposure to violent areas: integrating survey, smartphone, and administrative data resources. Annals of the American Academy of Pediatrics. 2017;669(1):41-62. In Chicago, Latinx children had 74 percent greater odds of exposure to violence, and Black children 112 percent greater odds, than white children.26Zimmerman GM, Messner SF. Individual, family background, and contextual explanations of racial and ethnic disparities in youths’ exposure to violence. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(3):435-442. When children in these cities are exposed to gun violence, their communities and schools often lack the resources to help them heal.27Kohli S, Lee I. What it’s like to go to school when dozens have been killed nearby. Los Angeles Times. February 27, 2019. https://lat.ms/2VrTDqt.

25%

Although Black students represent 15 percent of the total K-12 school population in America, they make up 25 percent of K-12 victims of gunfire at school.

US Department of Education. “State Nonfiscal Survey of Public Elementary and Secondary Education, 1998-99 through 2016-17; National Elementary and Secondary Enrollment by Race/Ethnicity Projection Model, 1972 through 2028,” Common Core Data (CCD). (2019). https://bit.ly/2Gl05d3

The disproportionate impact of gun violence on Black and Latinx children and teens extends to schools. Among the 335 incidents of gunfire at K-12 schools between 2013 and 2019, where the racial demographic information of the student body was known, 64 percent occurred in majority-minority schools.28Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund. Keeping Our Schools Safe: A Plan for Preventing Mass Shootings and Ending All Gun Violence in American Schools. everytownresearch.org/school-safety-plan. February 2020. Everytown gathered demographic information on the student population of each school included in the database for which data were available. A majority-minority school is defined as one in which one or more racial and/or ethnic minorities (relative to the US population) comprise a majority of the student population. Everytown identified the race of 102 of the 208 student victims identified in the database. Of those, 25 were identified as Black, 57 as white, 23 as Hispanic or Latino, 3 as Asian-Pacific Islander, and 4 as other. The analysis includes in the count of these victims both people shot and wounded and deaths resulting from homicides, non-fatal assaults, unintentional shootings, and suicides and incidents of self-harm where no one else was hurt. Although Black students represent approximately 15 percent of the total K-12 school population in America, they constitute 25 percent of the K-12 student victims of gunfire who were killed or shot and wounded on school grounds.29US Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics. Common Core of Data (CCD). “State nonfiscal survey of public elementary and secondary education,” 1998-99 through 2015-16; National elementary and secondary enrollment by race/ethnicity projection model, 1972 through 2027. Everytown averaged the student population size, both total and Black student populations, for the years 2013 to 2018. February 2018. https://bit.ly/2MTkw3C. Everytown identified the race of 95 of the 177 student victims identified in the database. Of those, 23 were identified as Black, 54 as white, 13 as Hispanic or Latino, 1 as Asian-Pacific Islander, and 4 as other. The analysis includes both injuries and deaths resulting from homicides, assaults, unintentional shootings, and suicides and incidents of self-harm where no one else was hurt, in the count of these victims.

While the above discussion shows the disparate experiences of gun violence by race and ethnicity, the data further show that gun violence is concentrated in specific neighborhoods in cities, with some schools and certain communities experiencing gun violence with an alarming frequency.

- Of the schools covered by gunshot detection technology in Washington, DC, just 9 percent experienced nearly half of all gunfire incidents. Four schools, including two middle schools and two high schools, had at least nine incidents of gunfire within just 500 feet of the school.30Bieler S, La Vigne N. Close-range gunfire around DC schools. Urban Institute. September 2014. https://urbn.is/2Hazr8y. Gunshot detection technology covered 66 percent (116 out of 175) of traditional public schools and charters during the study period.

- Similarly, in Los Angeles, 34 percent of middle school students in one neighborhood with high rates of violence reported exposure to firearm violence.31Aisenberg E, Ayón C, Orozco-Figueroa A. The role of young adolescents’ perception in understanding the severity of exposure to community violence and PTSD. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2008;23(11):1555-78.

- At certain urban middle schools in Texas, nearly 40 percent of boys and 30 percent of girls have witnessed a gun being pulled.32Barroso CS, Peters RJ, Kelder S, Conroy J, Murray N, Orpinas P. Youth exposure to community violence: association with aggression, victimization, and risk behaviors. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2008;17(2):141-155.

- A study of 7-year-olds in an urban neighborhood found that 75 percent had heard gunshots, 18 percent had seen a dead body, and 61 percent worried some or a lot of the time that they might get killed or die.33Hurt H, Malmud E, Brodsky NL, Giannetta J. Exposure to violence: psychological and academic correlates in child witnesses. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2001;155(12):1351-6.

The Far-reaching Impact of Children’s and Teens’ Exposure to Gun Violence

Children are harmed in numerous ways when they witness violence. Children exposed to violence, crime, and abuse are more likely to abuse drugs and alcohol; suffer from depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder; resort to aggressive and violent behavior; and engage in criminal activity.34Finkelhor D, Turner HA, Ormrod R, Hamby S, Kracke K. Children’s exposure to gun violence: a comprehensive national survey. US Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. https://bit.ly/PwXoZN. 2009; Morris E. Youth violence: implications for posttraumatic stress disorder in urban youth. National Urban League. https://bit.ly/2KBpOyg. March 2009; Fowler PJ, Tompsett CJ, Braciszewski JM, Jacques-Tiura AJ, Baltes BB. Community violence: a meta-analysis on the effect of exposure and mental health outcomes of children and adolescents. Development and Psychopathology. 2009;21(1):227-59. Exposure to community violence, including witnessing shootings and hearing gunshots, makes it harder for children to succeed in school.35Hurt H, Malmud E, Brodsky NL, Giannetta J. Exposure to violence: psychological and academic correlates in child witnesses. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2001;155(12):1351-6; Schwartz D, Gorman AH. Community violence exposure and children’s academic functioning. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2003;95(1):163-173.

Children’s exposure to gun violence can also erode physical health. When children live in neighborhoods where gun violence is common, they spend less time playing and being physically active, with one study finding that children said they would engage in an additional hour of physical activity every week if safety increased in their neighborhood.36Molnar BE, Gortmaker SL, Bull FC, Buka SL. Unsafe to play? Neighborhood disorder and lack of safety predict reduced physical activity among urban children and adolescents. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2004;18(5):378-86.

Stress related to gun violence affects student performance and well-being in schools. School-aged children have lower grades and more absences when they are exposed to violence.37Hurt H, Malmud E, Brodsky NL, Giannetta J. Exposure to violence: psychological and academic correlates in child witnesses. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2001;155(12):1351-6; Schwartz D, Gorman AH. Community violence exposure and children’s academic functioning. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2003;95(1):163-173. High school students who have been exposed to violence have lower test scores and lower rates of high school graduation.38Harding DJ. Collateral consequences of violence in disadvantaged neighborhoods. Social Forces. 2009;88(2):757-784; Finkelhor D, Turner H, Shattuck A, Hamby S, Kracke K. US Department of Justice, Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Children’s exposure to gun violence, crime, and abuse: an update. September 2015. https://bit.ly/2tK7ah6. One study estimated that Black children in Chicago’s most violent neighborhoods spend at least a week out of every month functioning at lower concentration levels due to local homicides.39Sharkey P. The acute effect of local homicides on children’s cognitive performance. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107(26):11733-11738. In Syracuse, NY, elementary schools located in areas with high concentrations of gunshots had 50 percent lower test scores and higher rates of standardized test failure compared to elementary schools in areas with a low concentration of gunshots.40Bergen-Cico D, Lane SD, Keefe RH. Community gun violence as a social determinant of elementary school achievement. Social Work in Public Health. 2018;33(7-8):439-448.

Black high school students in the US are over twice as likely as white high school students to miss school due to safety concerns.41Sheats KJ, Irving SM, Mercy JA, et al. Violence-related disparities experienced by Black youth and young adults: opportunities for prevention. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2018;55(4):462-469. In Chicago, following spikes in neighborhood violence, students reported feeling less safe, experiencing more disciplinary problems, and having less trust in teachers.42Burdick-Will J. Neighborhood violence, peer effects, and academic achievement in Chicago. Sociology of Education. 2018;91(3):205-223.

Recommendations

One essential way to protect our youth and prevent children’s exposure to gun violence in their communities and schools is to prevent people with dangerous histories from ever getting a gun. Recommendations for comprehensive gun safety laws include:

Background checks on all gun sales

The foundation of any comprehensive gun violence prevention strategy must be background checks for all gun sales. Under current federal law, criminal background checks are required only for sales conducted by licensed dealers. This loophole is easy to exploit and makes it easy for convicted felons or domestic abusers to acquire guns without a background check simply by finding an unlicensed seller online or at a gun show.

Extreme Risk laws

These laws, increasingly being adopted by states, empower family members and law enforcement to petition a judge to temporarily block a person from having guns if they pose a danger to themselves or others. Extreme Risk laws—also known as Red Flag laws—can help prevent suicide, too. That is meaningful because nearly six out of every 10 gun deaths are suicides,43Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. WONDER Online Database, Underlying Cause of Death. Firearm suicide deaths to total gun deaths ratio developed using four years of the most recent available data: 2018 to 2021. and the suicide rate among children and teens has been increasing exponentially in the past 10 years.

Secure gun storage and child access prevention laws

Secure storage laws require people to store firearms responsibly to prevent unsupervised access to firearms. A subset of these laws, known as child access prevention laws, specifically target unsupervised access by minors. Secure firearm storage practices are associated with reductions in the risk of self-inflicted and unintentional firearm injuries among children and teens—up to 85 percent depending on the type of storage practice.44Grossman DC, Mueller BA, Riedy C, et al. Gun storage practices and risk of youth suicide and unintentional injuries. JAMA. 2005;293(6):707-714. Study found households that locked both firearms and ammunition had an 85 percent lower risk of unintentional firearm deaths than those that locked neither.

Keeping guns out of the hands of domestic abusers

Children are frequent casualties of domestic violence homicides when a gun is involved. Research also shows that the presence of a gun in a domestic violence situation makes it five times more likely that a woman will be killed.45Campbell JC, Webster D, Koziol-McLain J, et al. Risk factors for femicide within physically abuse intimate relationships: results from a multisite case control study. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(7):1089-1097. It is imperative to keep guns out of the hands of domestic abusers to keep women, children, and their families safe. When abusers are convicted of domestic violence or subject to final restraining orders, they should be blocked from purchasing guns and required to turn in those they already own. We also need to close the “boyfriend loophole” by making sure those laws apply to abusers regardless of whether the violence is directed towards a spouse or a dating partner.

In addition to evidence-based gun safety laws, there are a number of programs and strategies that communities and schools can adopt to keep children and teens safe from gun violence, some examples of which include:

Threat assessment programs

Threat assessment programs—like the Everytown and AFT-endorsed Comprehensive Student Threat Assessment Guidelines (CSTAG)46Cornell DG, Sheras PL. Guidelines for responding to student threats of violence. Longmont, CO: Sopris West; 2006.—help schools identify students who are at risk of committing violence and get them the help they need in order to resolve student threat incidents.47Ibid. The programs generally consist of multi-disciplinary teams that are specifically trained to intervene at the earliest warning signs of potential violence and divert those who would do harm to themselves or others to appropriate treatment. Several studies have found that schools that use threat assessment programs see fewer students carry out threats of violence; and experience fewer suspensions, expulsions, and arrests.48Cornell, D, Maeng, J, Burnette AG., et al. Student threat assessment as a standard school safety practice: results from a statewide implementation study. School Psychology Quarterly. 2017;33(2):213-222; Cornell D., Maeng, J. Burnette AG, Datta P, Huang F, Jia Y. Threat assessment in Virginia schools: technical report of the Threat Assessment Survey for 2014-2015. Curry School of Education, University of Virginia. May 12, 2015; Cornell DG, Allen K, Fan X. A randomized controlled study of the Virginia Student Threat Assessment Guidelines in kindergarten through grade 12. School Psychology Review. 2012;41(1):100-115. Importantly, studies have shown that CSTAG threat assessment programs generally do not have a disproportionate impact on students of color.49Ibid.

Safe and equitable schools

School communities must look inside their schools to make sure they are encouraging effective partnerships between students and adults, while also looking externally to ensure that they are a key community resource. Schools should review discipline practices and ensure threat assessment programs are not adversely affecting school discipline. They should work to become “community schools” by building effective community partnerships that provide services that support students, families, and neighborhoods. If and when employing school resource officers (SROs), schools should take steps to build relationships between communities and law enforcement.

Youth-centric intervention programs

A variety of programs exist to help children cope with witnessing firearm violence. School-based programs, including social emotional learning, have been shown to reduce the negative effects of children’s exposure to gun violence. Mentoring programs are effective at improving academic performance and reducing youth violence. Chicago’s Safe Passage program makes children feel safer on their way to and from school and may increase school attendance. To learn more about two specific organizations that help children succeed after witnessing violence, please explore these resources about the Hip Hop Heals and Becoming A Man programs.

If you or someone you know has been exposed to gun violence, there are resources that can help. Everytown’s Children’s Responses to Trauma provides information for parents and adults about how to support children and teens who have experienced a shooting or are upset by images of gun violence. Additional information to help with the emotional, medical, financial, and legal consequences of gun violence for individuals and communities is on our Resources page.

Everytown Research & Policy is a program of Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, an independent, non-partisan organization dedicated to understanding and reducing gun violence. Everytown Research & Policy works to do so by conducting methodologically rigorous research, supporting evidence-based policies, and communicating this knowledge to the American public.