Fatal Gaps

How the Virginia Tech Shooting Prompted Changes in State Mental Health Records Reporting

Summary

In 2007, 32 people were shot and killed and 17 others were wounded at Virginia Tech. The shooter was prohibited from possessing firearms due to a court judgment that he was a danger to himself and others, but his records were never submitted to the FBI’s National Instant Criminal Background Check System (“NICS”). As a result, he was able to pass several background checks to purchase the guns he used in the shooting.

In the wake of this mass shooting, lawmakers took action to close the fatal gaps in state mental health records reporting that undermine the background check system and threaten the safety of Americans. This report documents ten years of progress, examines its key drivers, and underscores the vital importance of state and federal laws that govern and support mental health records reporting.

Notwithstanding this progress, it is likely that hundreds of thousands of prohibiting mental health records are missing from the background check system, potentially enabling prohibited people to purchase firearms illegally. To close these fatal gaps, the seven states that do not have mental health reporting laws should pass and implement strong laws. All 50 states need laws that require prompt submission of all prohibiting records and federal funding to support the submission process. States should regularly audit their submission processes to ensure no records are falling through the cracks.

Key Points

-

In the past 10 years, 35 states have improved records reporting by passing new reporting laws, 16 states have improved existing laws, and 29 states have accessed federal funding.

-

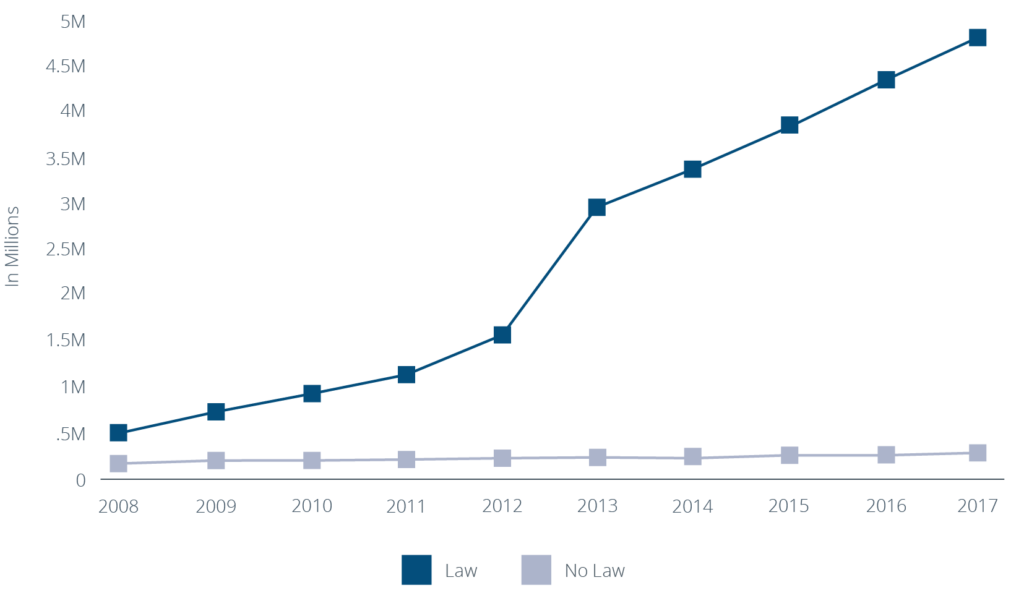

As a result of state reporting laws and federal funding, mental health records submitted by states have increased by nine times and gun sale denials have increased by 11 times.

-

States with mental health reporting laws submitted more than twice as many records per capita as states without these laws.

-

The states with the highest submission rates per capita had reporting laws and had received federal funding.

Introduction

Screening gun buyers with a background check is the backbone of any comprehensive gun violence prevention strategy, and it works to keep firearms out of the hands of people who pose a danger of violence to themselves or others. Since its inception in 1994, the background check system has blocked over 3 million sales to people prohibited by federal or state law from possessing guns1Karberg JC, Frandsen RJ, Durso JM, et al. Background Checks for Firearm Transfers, 2015. Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2017. Data for 2016 and 2017 were obtained by Everytown from the FBI directly. Though majority of the transactions and denials reported by FBI and BJS are associated with a firearm sale or transfer, a small number may be for concealed carry permits and other reasons not related to a sale or transfer. — including convicted felons, domestic abusers, and people prohibited due to mental illness.*

The foundation of a background check is the FBI’s National Instant Criminal Background Check System (“NICS”) — the system that enables a quick determination on whether a prospective gun buyer is eligible to buy firearms. But a background check is only as good as the records in the NICS databases and the submission of those records largely falls to state courts and law enforcement agencies.

Any missing record is a tragedy waiting to happen.2The problem of missing records was recently brought to national attention by the mass shooting at Sutherland Springs, Texas in November 2017, where a shooter opened fire in a church, killing 26 people. Two years prior, the shooter was discharged from the U.S. Air Force after being court martialed for assaulting his wife and fracturing the skull of his infant stepson. This conviction prohibited him from possessing firearms under federal law; however, the Air Force failed to enter the record of the conviction into the federal database. As a result, the shooter was able to pass a background check and purchase the rifle used in the shooting from a licensed gun dealer. After the shooting, an Inspector General report revealed that the military had failed to tell the FBI about 31 percent of service members’ criminal convictions between 2015 and 2016, and had not met reporting requirements for over 20 years. The Sutherland Springs shooting underscores the fact that, despite the progress being made in states that have improved mental health records reporting, further work is needed by states and federal agencies to close the gaps that exist in federal records reporting. The Air Force has since committed to evaluating all reportable offenses going back to 2002 and putting new procedures in place to make sure the proper requirements are being met. Indeed, states’ failures to submit records to NICS have enabled prohibited people to pass background checks and purchase firearms, to devastating effect. This problem has been especially acute with mental health records.

The Virginia Tech mass shooting called attention to fatal gaps in record submissions that undermine the background check system and threaten the safety of communities across the country.3Luo M. U.S. Rules made killer ineligible to purchase gun. New York Times. April 21, 2007. In response to the shooting, Congress passed the NICS Improvement Amendments Act of 2007 (the “NICS Improvement Act”), creating a system of financial incentives to encourage robust state reporting.4Note that the federal government cannot constitutionally require states to submit prohibiting records, and must instead incentivize submission by other means. States have since taken action by passing or strengthening record reporting laws, accessing federal funding to improve their systems, and doing the work of getting records into NICS.

Everytown for Gun Safety has long been a leader in this area, interviewing state officials in 50 states, authoring two reports on mental health records, Fatal Gaps and Closing the Gaps , and advocating in statehouses to improve state reporting.

In this new report, Everytown for Gun Safety analyzed the NICS Indices database obtained from the FBI for the years 2008 to 2017, the earliest and latest years for which data were made available.5Everytown for Gun Safety received state records and denial data directly from the FBI via FOIA request. NARIP funding data was downloaded directly from the BJS website, available here: www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=tp&tid=491. Everytown analyzed the state laws and policies governing reporting laws. The data show that significant progress has been made throughout the country, led by states that have strengthened their records reporting infrastructures through legislation and federal funding. As a result, the number of mental health records in NICS has drastically increased and more gun sales have been denied to people prohibited due to mental illness.

*A diagnosis of mental illness alone does not prohibit a person from gun possession. Rather, the federal prohibition applies to any person: involuntarily committed to a psychiatric facility; found by a court or other authority to be a danger to self or others due to mental illness; found guilty but mentally ill, not guilty by reason of insanity, or incompetent to stand trial; or appointed a guardian due to mental illness. 18 USC 922(g)(4), 27 CFR 478.11.

Progress Toward a Stronger Background Check System

More than ten years after the Virginia Tech shooting, progress in closing the gaps in state mental health records submissions is evident in several key areas: legislation passed, federal funding accessed, mental health records submitted, and gun sales denied to prohibited people.

States have adopted or fixed reporting laws

In 2007, only eight states had laws requiring or explicitly authorizing the reporting of prohibiting mental health records to NICS. Between 2007 and 2017, 35 states passed new reporting laws and, by the end of 2017, 43 states had reporting laws in place. In that same time period, 16 of those states have also amended and improved existing laws.

In the last 10 years, 35 states passed mental health records reporting laws

States With Mental Health Records Reporting Laws in 2007

States With Mental Health Records Reporting Laws in 2017

Last updated: 7.2.2018

States have used federal funding to strengthen their systems

The NICS Improvement Act made new federal funding available to states, known as the NICS Act Record Improvement Program (“NARIP”) funding, for upgrading their systems to submit NICS records. Only states that have begun the work of submitting their mental health records1States must make estimates of the number of total mental health records to be submitted and must establish a qualifying relief from disabilities program that enables prohibited people to apply for the restoration of their rights when they no longer pose a danger. are eligible to apply for and receive NARIP funding. In 2009, the first year in which funding was made available, three states received federal NARIP funding. By the end of 2017, twenty-nine states had received this funding — and in total, the program has awarded nearly $119 million since its inception.

Twenty-nine states have received a total of $119 million in federal NARIP funding to improve mental health reporting

Last updated: 7.2.2018

Mental health record reporting by the states has improved

Between December 2008 and December 2017, the first and latest year for which data are available, the number of state-submitted mental health records in NICS increased by more than nine times, from just over 531,000 to nearly 4,973,000. In 2008, there were 35 states (along with Washington, D.C.) with less than 100 records submitted. In 2017, only two states had submitted fewer than 100 mental health records.

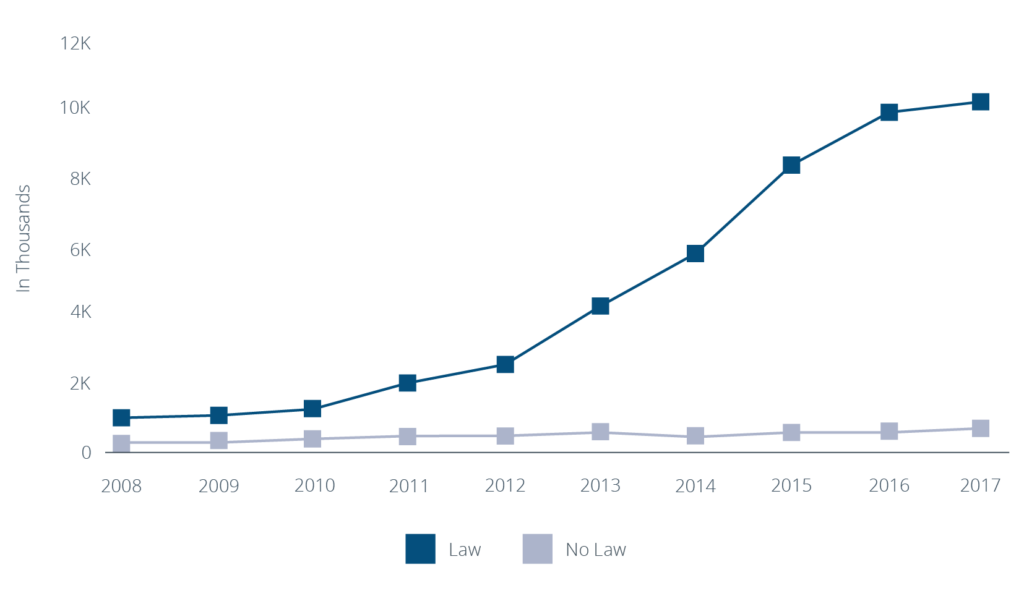

More prohibited persons are blocked from buying guns

As the number of mental health records in NICS has increased, so has the number of firearm sale denials to individuals prohibited due to mental illness. Since 2008, the number of these denials has increased by 11 times, from approximately 960 annual denials to over 11,000 in 2017.

Ten Years After Virginia Tech, Mental Health Records Submitted Have Increased by 9 Times; Denials Have Increased by 11 Times

Reporting Laws And Federal Funding Are Key To Closing The Gaps

State reporting laws matter. The 43 states with laws requiring or explicitly authorizing reporting have dramatically improved their records submission, particularly in comparison to the seven states (along with D.C.) without reporting laws.

States that have reporting laws for mental health records have experienced a significant improvement in the number of records submitted.

- In the 43 states with reporting laws in place, the number of prohibiting mental health records in NICS increased by 11 times between 2008 and 2017.

- Over the same time period, mental health records in the seven states (along with D.C.) without reporting laws also increased, but at a drastically slower rate of only two times.

- In 2017, the 10 states with the highest record submission rates per capita2While no national benchmark or minimum requirement for number of records submitted by each state exists (see more in the Records and Denials by State section), the record submission rate on the basis of the state population provides an opportunity to analyze any trends in the data. all had a reporting law in place.

States With Mental Health Reporting Laws Have Experienced a Significant Improvement in Number of Records Submitted Compared to States Without These Laws

In the absence of reporting laws, seven states — Arkansas, Ohio, Michigan, Montana, New Hampshire, Utah, Wyoming — and D.C. are likely underreporting mental health records, with some states submitting only a handful every year. Compared to states with reporting laws, these seven states and D.C. are reporting records at a significantly lower rate.

- In fact, states with reporting laws have submitted more than twice as many records per capita than states without laws — 1,600 vs. 700 per 100,000 people, respectively. Importantly, a large portion of the records submitted by states without laws are submitted by Michigan and Ohio, both of which have agency policies in place in the absence of laws.

- Six of the seven states, along with D.C., are in the bottom half of record submission rate per capita and four of those states are in the bottom ten performing states.

- Two states — Montana and Wyoming — have submitted fewer than 100 mental health records, and Wyoming, has submitted fewer than 10 records since 2007.

States With Mental Health Reporting Laws Submitted More Than Twice as Many Records Per Capita as States Without These Laws

Last updated: 7.2.2018

In addition to state laws, it is important to consider the impact of federal funding in improving reporting structures. By the end of 2017, 29 states with mental health reporting laws had received NARIP funding. And that funding made a difference: The states with the highest submission rates per capita had reporting laws and had received NARIP funding.

- Of the 10 states with the highest record submission rates per capita, eight had a reporting law in place and received NARIP funding.

States with more records in the system are better situated to prevent prohibited people from purchasing guns.

As the number of mental health records in NICS has increased, so has the number of firearm sales denied to people prohibited by mental illness. The states that have the lowest submission rates are also experiencing the lowest denial rates.

- In the 43 states with reporting laws in place, the number of annual denials was nearly 13 times higher in 2017 than in 2008, increasing from 822 in 2008 to 10,281 in 2017.

- During the same time period, annual denials in the seven states and D.C. without reporting laws increased only five times, increasing from 145 to 794. Again, the majority of the denials in states without laws occurred in the two states with agency policies in place, Michigan and Ohio.

States With Mental Health Reporting Laws Block More Gun Sales to People Prohibited Due to Mental Illness Compared to States Without These Laws

The details of a reporting law matter.

Not every state reporting law is as comprehensive as it could be. Evidence suggests that certain components of state reporting laws are associated with better records reporting outcomes.

- Of the 10 states with the highest record submission rates per capita, there are eight that require reporting, rather than merely authorizing it. These states provide clear statutory direction that records must be reported so that a change in political will or funding does not hold back progress.3Indeed, at the time of the original Fatal Gaps, officials in at least eight states said that a lack of political will stood in the way of passing new laws or reporting records.

Notably, these laws also vary in whether they require reporting of prohibiting records created before their enactment date — or else whether the state is required only to send in records on a prospective basis, enabling many prohibited people to pass a background check and buy a gun. States can also strengthen their laws and, in turn, their reporting systems, by ensuring that records are reported both from courts and also from mental health facilities, as appropriate — and by explicitly setting a short reporting timeframe for required submission. Finally, if states fail to establish a qualifying relief from disabilities program that enables prohibited people to apply for the restoration of their rights when they no longer pose a danger, the state is not eligible for NARIP funding.

Conclusion And Recommendations

Despite widespread progress in the improvement of reporting systems, there are likely hundreds of thousands of prohibiting mental health records that remain missing from NICS. Until these records are submitted, prohibited people, including those who are at very high risk of violence, will be able to purchase firearms without restriction.

To close these fatal gaps in NICS and help keep our communities safe:

- All 50 states need reporting laws. The seven states (along with D.C.) without mental health record reporting laws — Arkansas, Ohio, Michigan, Montana, New Hampshire, Utah, and Wyoming — need to pass and implement strong reporting laws.

- States with laws in place should apply for federal funding to support the submission process, and in turn, improve their records submissions.

- States should ensure that their reporting laws include provisions that

- Require reporting rather than merely authorizing it.

- Apply to prohibiting records that existed before the laws were enacted.

- Ensure that records from courts and health facilities are submitted.

- Require all records to be submitted within a short, designated period of time following the prohibiting event.

- Submission processes should be audited regularly and updated accordingly by states to ensure no records are falling through the cracks.

Appendix A: Records And Denials By State

There are many factors that affect the number of records a state has submitted to NICS, including state laws and funding streams, as well as differing mental health treatment rates, standards, and approaches that may impact how many people in a given state will be involuntarily committed, adjudicated as a danger to self or others, or otherwise prohibited by law. These factors vary significantly from state to state and make accurate and meaningful inter-state comparisons difficult. As a result, there exists no national benchmark or minimum requirement for the number of mental health records that should be submitted by each state.4United States Government Accountability Office, Gun Control: Sharing Promising Practices and Assessing Incentives Could Better Position Justice to Assist States in Providing Records for Background Checks; 2012.

While precise state comparisons may not be possible, we can look at the number of records submitted by each state and analyze trends that exist within those states over time. This analysis helps illustrate that the top reporting states have a combination of strong state laws and have received federal funding, while the bottom performing states have neither.

Presented below is a summary of mental health records data and rate of records, adjusted by population, and gun sales denied due to mental health for each state for 2008 and 2017.

| STATE | RECORDS 2008 | RECORDS 2017 | RECORDS RATE 2017 (PER 100K) | DENIALS 2008 | DENIALS 2017 |

| Alabama | 155 | 5,306 | 109 | 32 | 125 |

| Alaska | 0 | 267 | 36 | 11 | 19 |

| Arizona | 1,496 | 30,741 | 438 | 43 | 196 |

| Arkansas | 733 | 3,757 | 125 | 23 | 128 |

| California | 223,635 | 821,905 | 2,079 | 42 | 314 |

| Colorado | 15,677 | 77,364 | 1,380 | 57 | 534 |

| Connecticut | 4,296 | 63,394 | 1,767 | 0 | 0 |

| Delaware | 0 | 16,359 | 1,701 | 1 | 88 |

| District of Columbia | 80 | 694 | 100 | 0 | 1 |

| Florida | 18,580 | 151,859 | 724 | 80 | 848 |

| Georgia | 3,257 | 11,063 | 106 | 42 | 202 |

| Hawaii | 1 | 7,593 | 532 | 0 | 0 |

| Idaho | 0 | 36,148 | 2,105 | 8 | 141 |

| Illinois | 1 | 47,555 | 371 | 0 | 1 |

| Indiana | 2 | 10,484 | 157 | 12 | 118 |

| Iowa | 49 | 49,089 | 1,561 | 4 | 147 |

| Kansas | 2,384 | 6,908 | 237 | 20 | 79 |

| Kentucky | 2 | 36,501 | 819 | 26 | 253 |

| Louisiana | 1 | 5,518 | 118 | 29 | 80 |

| Maine | 24 | 4,330 | 324 | 2 | 22 |

| Maryland | 23 | 20,012 | 331 | 5 | 49 |

| Massachusetts | 0 | 14,320 | 209 | 0 | 12 |

| Michigan | 79,756 | 147,941 | 1,485 | 46 | 277 |

| Minnesota | 0 | 60,537 | 1,086 | 8 | 159 |

| Mississippi | 1 | 14,893 | 499 | 17 | 244 |

| Missouri | 19,575 | 48,766 | 798 | 59 | 235 |

| Montana | 1 | 36 | 3 | 14 | 33 |

| Nebraska | 2 | 30,642 | 1,596 | 1 | 49 |

| Nevada | 0 | 7,141 | 238 | 0 | 66 |

| New Hampshire | 1 | 519 | 39 | 0 | 10 |

| New Jersey | 2 | 447,563 | 4,970 | 0 | 34 |

| New Mexico | 0 | 7,506 | 359 | 13 | 80 |

| New York | 5 | 544,398 | 2,743 | 15 | 512 |

| North Carolina | 1,256 | 399,320 | 3,887 | 45 | 1050 |

| North Dakota | 1 | 3,258 | 431 | 3 | 34 |

| Ohio | 15,990 | 56,390 | 484 | 57 | 252 |

| Oklahoma | 1 | 3,004 | 76 | 35 | 82 |

| Oregon | 1 | 27,075 | 654 | 0 | 102 |

| Pennsylvania | 0 | 831,886 | 6,496 | 0 | 1,717 |

| Rhode Island | 0 | 444 | 42 | 0 | 7 |

| South Carolina | 7 | 85,807 | 1,708 | 30 | 492 |

| South Dakota | 0 | 1,047 | 120 | 7 | 27 |

| Tennessee | 33 | 40,186 | 598 | 0 | 225 |

| Texas | 7 | 284,549 | 1,005 | 87 | 704 |

| Utah | 38 | 10,211 | 329 | 1 | 73 |

| Vermont | 1 | 1,310 | 210 | 1 | 20 |

| Virginia | 105,782 | 292,025 | 3,448 | 15 | 488 |

| Washington | 38,428 | 124,483 | 1,681 | 54 | 259 |

| West Virginia | 0 | 49,249 | 2,712 | 14 | 345 |

| Wisconsin | 7 | 31,371 | 541 | 4 | 122 |

| Wyoming | 4 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 20 |

Appendix B: Mental Health Records And The NICS

Mental Health Records Submission And The National Instant Background Check System (NICS)

Learn More:

- Alert Local Law Enforcement of Failed Background Checks

- Background Checks on All Gun Sales

- Guns in Schools

- Keep Guns Off Campus

- Keeping Guns Out of the Wrong Hands

- Mass Shootings

- Prohibit High-Capacity Magazines

- Prohibit People With Dangerous Histories From Having Guns

- Require Prohibited People to Turn in Their Guns

- Threat Identification and Assessment Programs in Schools

Everytown Research & Policy is a program of Everytown for Gun Safety Support Fund, an independent, non-partisan organization dedicated to understanding and reducing gun violence. Everytown Research & Policy works to do so by conducting methodologically rigorous research, supporting evidence-based policies, and communicating this knowledge to the American public.