Dr. Harel Shapira: How Attitudes About Guns Develop Over Time

1.26.2023

Safety in Numbers

Welcome to Everytown Research’s Safety in Numbers blog, where we invite leading experts in the growing field of gun violence prevention to present their innovative research in clear, user-friendly language. Our goal is to share the latest developments, answer important questions, and stimulate evidence-based conversations on a broad range of gun safety topics in a form that allows all of us to participate. If you have a topic you want to hear more about, please feel free to suggest it at: [email protected].

Sarah Burd-Sharps, Senior Director of Research

Note: The views, opinions, and content expressed in this product do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or policies of Everytown.

Dr. Shapira and his colleagues Ken-Hou Lin, Chen Liang, and Patrick Sheehan, wanted to conduct research that deviated from the usual question, “What do people think about guns?” to instead ask: “How do people’s attitudes about guns develop?” In asking this question, they wanted to understand gun attitudes as the outcomes of social processes, to explore what leads people to think about guns in the ways that they do, and to learn more about whether people’s attitudes about guns change over time.

Prior research has identified young adulthood, especially college, as a transformative life stage in which political beliefs are formed, therefore, their research is focused on a national sample of college students across the United States. The decision to concentrate on this population is also influenced by the growing focus on this group in political mobilization efforts around gun policy as well as the high levels of political participation among college students.

“While we know a great deal about what people think about guns, we actually know very little about how those attitudes are formed in the first place. Relatedly, while surveys on gun attitudes help show us what people think about guns, they present those attitudes as fixed and fully formed,” Dr. Shapira said.

Learn more about Dr. Shapira’s research in his own words:

Existing research suggests that people who grew up in gun-owning families tend to have positive attitudes about guns, including being less supportive of gun regulations than those who did not grow up in gun-owning households. But what drives this attitude? Our first finding is that while family gun ownership matters, what matters more is the extent that children are actively socialized around guns during childhood through activities such as target shooting or hunting with family. In other words, it is not family gun ownership that drives the effect on attitudes, but the socialization around guns. Through such experiences, young adults develop positive emotional and physical pleasure toward guns. These positive experiences are as much about shooting the gun itself as they are about the experience of bonding with others over a gun-related activity, particularly when it comes to boys bonding with male family members or with other boys. For all its ideological emphasis on individuality, gun culture is deeply social.

Just because you grow up in a gun-owning household, that does not mean you will be socialized into gun culture. In fact, while some children who grow up in gun-owning households do not experience socialization around guns, some children who grow up in households without guns do experience such socialization. And as a result, it is this latter group who end up expressing more pro-gun attitudes: young adults who did not grow up in gun-owning families but who had experiences shooting guns before the age of 18 expressed a greater desire to own a gun in the future than young adults who grew up in gun-owning households but never shot a gun. In fact, the impact of experiences shooting guns is so powerful, that young adults who shoot guns before the age of 18 are more likely than those who have not shot guns—regardless of their family’s political orientation—to oppose a background check for private gun sales and mandatory safety training for gun owners.

Exploring the role of socialization is an important component of this research.

Socialization around guns continues beyond childhood. In college, for example, young adults may become friends with gun owners and be exposed to activities such as target shooting or hunting. And just as childhood socialization impacts their attitudes about guns, so does socialization that happens in young adulthood. Consequently, we can begin to see the formation of attitudes about guns as an evolving process; dynamic, and even subject to change. Sometimes, even those who grow up with one set of attitudes about guns can change their attitudes as a result of experiences in young adulthood, coming from a family that is “pro-gun” and subsequently developing “anti-gun” beliefs, and vice versa.

A key driver in the formation of gun attitudes is people’s relationships. Whether we are talking about relationships with family members, friends, or romantic partners, we find that people’s attitudes about guns are influenced by the attitudes that the people with whom they socialize hold toward guns. And as their relationships change, so too do those attitudes. Meeting new friends or starting to date someone can significantly impact a person’s attitudes about guns. Our data show that friendships with gun owners are more important for people’s attitudes about guns than coming from a gun-owning family. Indeed, young adults with one or more gun-owning friends are more likely to want to own guns in the future than those who do not have any gun-owning friends, even when they come from a gun-owning family.

In the transition to young adulthood, attitudes about guns develop from being articulated primarily as personal experiences connected to the activity of shooting guns or experiencing gun violence to being articulated as political beliefs connected to regulation issues.

As relationships change, so do people’s attitudes about guns.

We should think of gun attitudes not as something static and fully formed but rather as outcomes of social processes. One important implication of this is that scholars and policymakers should consider a developmental perspective to studying gun attitudes and examine the social processes through which gun attitudes develop. While one’s attitudes about guns tend to become more stable later in life, we suspect that changes in relationships through life events such as moving, divorce, or having kids, may still influence adults’ attitudes about guns.

Because experiences of socialization around guns are influential due to the social bonding that comes with it, guns are meaningful to people not merely for ideological reasons or matters of crime and safety, but as sources of community, relationship formation, and belonging. People’s attitudes about guns are intimately tied to their attitudes about gun owners. Gun attitudes should not be thought of as individual traits but rather as relational properties—with these attitudes emerging in the context of social relationships. As a result, any efforts to change attitudes about guns focusing on either statistics or cultural values without considering the relationships through which those statistics or values emerge and are given meaning will have a limited impact.

Parents play a critical role in shaping youth attitudes toward guns and gun ownership.

Because childhood socialization around guns plays a key role in the formation of our attitudes, and relationships play a key role in attitude formation as well, there is probably no one more influential in shaping youth attitudes about guns than their parents. That means recognizing that parents who choose to teach their children how to shoot a gun should not only focus on teaching gun safety, but should also teach their children how guns impact our society. Doing so effectively and accurately entails thinking about matters that we may not directly associate with “gun policy.” For example, teaching children about racism or a version of masculinity that does not require aggression is as important as teaching them about safe gun handling when it comes to teaching children how to become responsible gun owners in adulthood.

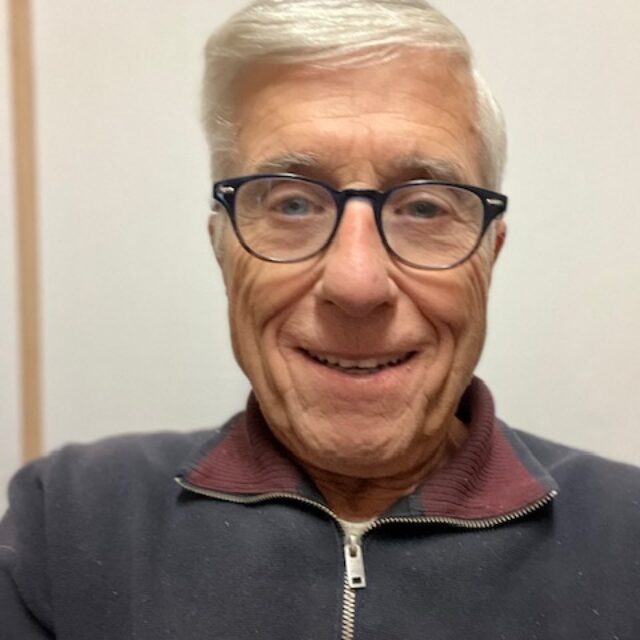

About Dr. Shapira

Harel Shapira, Ph.D, is an Associate Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Texas at Austin. His research focuses on gun culture, militias, and right-wing politics. He loves fly fishing and has a dachshund named Durkheim.