David Riedman: Using “First Principles” Thinking to Decrease School Shootings by 10x

1.16.2025

Safety in Numbers

Welcome to Everytown Research’s Safety in Numbers blog, where we invite leading experts in the growing field of gun violence prevention to present their innovative research in clear, user-friendly language. Our goal is to share the latest developments, answer important questions, and stimulate evidence-based conversations on a broad range of gun safety topics in a form that allows all of us to participate. If you have a topic you want to hear more about, please feel free to suggest it at: [email protected].

Sarah Burd-Sharps, Senior Director of Research

Note: The views, opinions, and content expressed in this product do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or policies of Everytown.

There have been at least 300 shootings on school campuses each of the last three years. The year 2024 saw a 5 percent reduction from 2023, but the total was still 10 times higher than a decade ago. When these numbers represent bullets flying down school hallways and kids’ lives, what can we do to reduce this problem by 10x?

If you want to make around $3 million per year in profits, you can buy and run a hotel. If you are really clever with branding and marketing, maybe you can make $8 million instead of $3 million by tweaking some aspects of the business.

If you want to make $8 BILLION instead of $8 million, you challenge the basic assumption that guests stay in a hotel, and you create a website to rent empty houses and apartments to travelers. This is how Airbnb used a concept called “first principles” thinking to upend the norms in the long-established travel industry. The basic concepts of this process are to:

- Break down problems into their simplest elements.

- Identify current assumptions.

- Challenge the assumptions and avoid analogous thinking.

- Create new solutions from scratch.

The current school security enterprise is driven by maintaining the status quo, repurposing ideas (e.g., castle-style fortified designs, hot spot policing, TSA-style screening, Secret Service model for identifying assassins targeting the president), and making little tweaks to existing programs for marginal gains at schools.

If we want to reduce the number of people shot on campus from 250 to 25, we need to use first principles to figure out the foundation of these problems and come up with completely new solutions. Putting another police officer on campus, an electronic lock on the front door, or sending the school administrators to a three-day threat assessment workshop is just continuing business as usual with another chain hotel.

More about First Principles

First principles thinking is a foundational problem-solving approach embraced by the most successful Silicon Valley billionaires. It involves breaking down complex problems into their most basic, fundamental truths and reasoning up from there. This approach enables innovative solutions by challenging the status quo and encouraging fresh perspectives.

- Breaking down problems: Instead of starting with existing solutions or frameworks, first-principles thinkers deconstruct problems into their simplest components. For example, Elon Musk applied first principles at Tesla by analyzing the raw material costs and building a new type of battery instead of accepting the market price for the previous generation of low-performance batteries.

- Identifying current assumptions: Many companies iterate on existing ideas (e.g., making a product slightly better). First-principles thinking seeks to question whether existing solutions address the fundamental problem. As I explained in the intro, Airbnb disrupted the hotel industry by asking, “What’s the fundamental purpose of a place to stay?” rather than improving traditional hotel models.

- Challenging assumptions: Innovators question why things are done a certain way and explore if those methods can be reimagined. SpaceX reimagined rocket design by questioning the basic assumption since the first fireworks were invented in China centuries ago that rockets must be single-use. Reusable rocket technology changes everything because it’s so much cheaper and allows for a higher volume of launches.

- Creating new solutions from scratch: By focusing on core, foundational components of a problem, entrepreneurs can innovate in directions that challenge the status quo of an established industry. It was taken for granted that product manufacturers use third-party companies for logistics and shipping. Amazon developed its own fulfillment and delivery systems instead of relying on third-party solutions, which significantly reduced costs, improved scalability, and created one of the biggest companies in the history of humanity.

What’s the equivalent to using first principles to land an 11-million-pound rocket—which everyone assumed was impossible, so they didn’t even try—when it comes to preventing gun violence on campus?

Break Problems Down into Their Simplest Elements

The core problem for school safety is how do we prevent people—students, staff, and community members—from being shot on school campuses?

The three most foundational elements are

- Someone is motivated to cause harm.

- That person can access a gun.

- A school campus is an open and accessible public place that people use every day.

If someone—usually a student—is motivated to cause harm and can get a gun, it’s easy for them to take the gun to a school.

From a first-principles standpoint, you can think of a school shooting as the combination of these elements. If any of the three is disrupted—(1) the individual’s motivation toward violence is changed, (2) access to firearms is significantly constrained, or (3) the open-school environment is restructured—the likelihood of a school shooting happening decreases dramatically.

Identify the Current Assumptions

Tweaking the status quo at schools might reduce the problem by 5 to 10 percent. Just look at policing and crime rates since we started recording crime data in the 1930s. We have collectively spent trillions of dollars on policing just to have small dips in the overall rate of crime. Following conventional thinking, assigning more officers to a school campus—known as “hot spot policing”—is an expensive, intrusive, and generally ineffective way to maybe achieve a small reduction in gun violence rates.

Completely eliminating a problem like school shootings requires a clean sheet of paper, which is a radical change. Here are seven assumptions that have become the status quo for school security:

- Conventional thinking assumption 1: More police and armed security is the best way to prevent shootings.

- Conventional thinking assumption 2: Fortified buildings will keep a school shooter out and protect the kids inside.

- Conventional thinking assumption 3: School shooters always show clear warning signs.

- Conventional thinking assumption 4: Schools need to be big campuses that students attend for multiple years on the same schedule every week (e.g., classes from 8 a.m. to 3 p.m. on Monday to Friday from September to June).

- Conventional thinking assumption 5: Gun control laws are politically infeasible, so we can’t do anything to regulate firearm storage and access.

- Conventional thinking assumption 6: Primary responsibility for student safety lies with schools and law enforcement.

- Conventional thinking assumption 7: If a shooting (or threat of a shooting) happens on campus, a school should go on lockdown with students hiding in the closets and corners of classrooms.

Challenge Assumptions and Avoid Analogous Thinking

Instead of asking, “How do we prevent school shootings?” why don’t we reframe it as, “How do we eliminate the conditions that allow school shootings to occur?”

This approach shifts the focus from reacting when it’s already too late to transforming the environment and societal dynamics that make a school shooting possible. This means questioning not just the methods but the very foundational assumptions underlying school safety, education systems, and social norms.

Challenge #1: Stop Hot Spot Policing in Schools

Conventional approaches typically involve stationing armed officers or security on campuses to deter shooters. In reality, police officers or armed security were on campus during most of the recent planned attacks, and that personnel did not deter or prevent the shooting. Armed security can unintentionally escalate situations, create a more militarized environment that negatively affects school climate, increase risks from accidental shootings and misplaced firearms, and may even make a school a more attractive target for a suicidal student who wants to die during a violent public shooting.

Another issue is the cost of police or school resource officers (SROs), particularly on large campuses that require many, up to dozens of, officers to effectively patrol. Allocating substantial funds for security in a resource-constrained school means that less funding goes to mental health services, counseling, reducing class sizes so that troubled students get noticed, or community programs that address the root causes of violence. If a shooting happens on campus, schools—just like any public places—already have access to an emergency police response by calling 911.

Instead of more status quo policing, schools can put this funding into proven violence-prevention strategies like crisis intervention, counseling, and conflict resolution training. By focusing on community building, fostering a positive school culture, and creating supportive services, schools can move away from a surveillance- and punishment-based model toward a more holistic and proactive approach that reduces or eliminates the conditions that create the crisis for a potential school shooter.

Learn more: Ep 28. Why School Police May Not Be the Best Way to Prevent Violence

Instead of duplicating old ideas, check out my full article on Substack School Shooting Data Analysis and Reports.

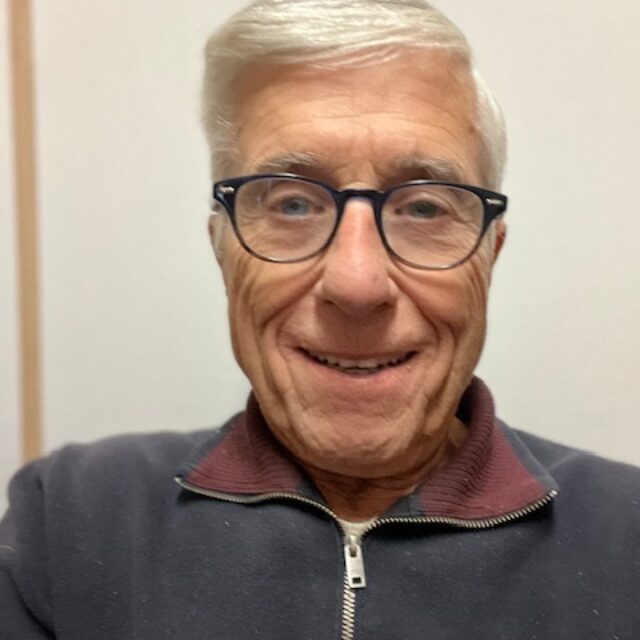

About David Riedman

David Riedman is the creator of the K–12 School Shooting Database, chief data officer at a global risk management firm, and a tenure-track professor. Listen to his weekly podcast—Back to School Shootings—or recent interviews on Freakonomics Radio, New England Journal of Medicine, and read his article on CNN about AI and school security.